To Sleep, Perchance to Dream

To Sleep, Perchance to Dream, one of the Exhibitions at the Folger, opened on February 19, 2009 and closed May 30, 2009. The exhibition was curated by Carole Levin and Garrett Sullivan with Steven K. Galbraith and Heather Wolfe as consultants.

While sleeping and dreaming are universal experiences, each culture and historical period understands them in distinctive ways. This exhibition explores the ethereal realm of sleeping and dreaming in Renaissance England, from the beliefs, rituals, and habits of sleepers to the role of dream interpreters and interpretations in public and private life.

The habits and attitudes of both royalty and commoners toward sleep and dreams provide us with a glimpse into a world that has strong connections with, and striking differences from, our own. Sufferers of insomnia and nightmares attempted to cure themselves with a variety of remedies—from herbal concoctions to magic. They adhered to specific rituals for going to bed and held beliefs about when it was or was not appropriate to sleep.

Through a variety of printed, handwritten, and visual materials, including literary texts by Shakespeare, Milton, and others, To Sleep, Perchance to Dream explores the vibrancy of early modern views of sleeping and dreaming. Nightclothes, gemstones, recipes and ingredients for curing nightmares and inducing sleep, and records of dreams about or by historical figures, provide a vivid glimpse of the various ways in which the Renaissance English prepared for sleep and sought to control and understand their dreams.

Contents of the exhibition

Preparing for Sleep

Medical writers understood sleep to be crucial to the maintenance of physical well-being, and offered specific instructions for a range of bedtime matters, such as identifying the best place to sleep, choosing a bed least likely to attract vermin, and selecting the most appropriate night clothes. Preparing for sleep was also a spiritual matter. Because of the widely held fear that one might die while asleep, saying one’s prayers was an important nightly ritual.

Several texts give insight into how people prepared for sleep in Renaissance England. Church of England clergyman Richard Day’s text, A booke of Christian prayers, offers both a bedtime prayer as well as images of sleepers sharing a bed. Primarily for reasons of economy and warmth, bed-sharing was a common practice in early modern households and in university settings.

Thomas Tryon’s A treatise of cleanness in meats and drinks, of the preparation of food, the excellency of good airs, and the benefits of clean sweet beds offers a wealth of sleep-related advice, which he summarizes as follows: “Therefore moderate Clothing, hard Beds, Houses that stand so as that the pleasant Briezes of Wind may air and refresh them, and also Houses that are full of Windows, are to be preferr’d.” He also notes that featherbeds breed vermin (a common problem in early modern beds) and are to be avoided.

Finally, Thomas Cogan's The haven of health covers topics such as the “most fit” place in which to sleep, the best way to make the bed, and the appropriate posture for sleeping. Cogan also notes that “he that sleepeth with his mouth close[d] hath commonly an ill breath and foule teeth.”

Items included

- Richard Day. A booke of Christian prayers, collected out of the auncient writers, and best learned in our tyme, worthy to be read with an earnest mynde of all Christians, in these daungerous and troublesome dayes, that God for Christes sake will yet still be mercyfull unto us. London: John Day, 1578. Call number: STC 6429 and LUNA Digital Image.

- Thomas Tryon. A treatise of cleanness in meats and drinks, of the preparation of food, the excellency of good airs, and the benefits of clean sweet beds. London, 1682. Call number: T3196.

- Thomas Cogan. The hauen of health: chiefely gathered for the comfort of students, and consequently of all those that have a care of their health, amplified upon five words of Hippocrates, written Epid. 6 Labor, cibus, potio, somnus, Venus. London: Henrie Midleton, for William Norton, 1584. Call number: STC 5478 and LUNA Digital Image.

When We Sleep

Night-time slumber was divided into “first” and “second” sleeps, separated by a period of wakeful activity. How many hours one should sleep was dictated by one’s humoral “complexion”—that is, the balance in the body of the four humors (blood, phlegm, choler or bile, and melancholy or black bile). Sleep was associated with cold and moisture, and therefore with phlegm, a cold, wet humor. Napping during the day was discouraged, as it was believed to cause, in the words of Thomas Cogan, “great domage & hurt of body.” And sleeping too much was both a physical and spiritual transgression.

Sleep was thought to be associated with the humors, which were closely related to a person's temperament. Both sloth and forgetfulness were moral vices associated with sleeping too long or at the wrong time of day.

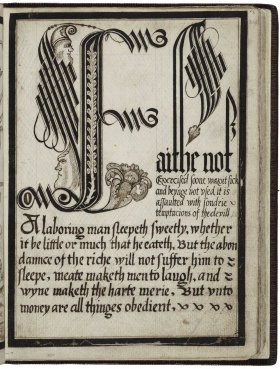

Thomas Fella's heavily-illustrated miscellany includes an “alphabet” of moral advice. The letter F is devoted to sleep—particularly the fitful sleep of the rich as compared to the sweet sleep of “a laboring man.”

And Scipion Du Plesis' The Resolver, a translation of the French Curiosité naturelle, poses and answers a question about the relative strength of “first sleep” that foregrounds the importance of digestion— namely that it produces fumes that ascend to the brain, and provokes sleep by “stop[ping] the conduits of the Senses.”

Items included

- Thomas Fella. A booke of diveirs devises and sortes of pictures, with the alphabete of letters, deuised and drawne with the pen. Manuscript, ca. 1585-1622. Call number: V.a.311 and LUNA Digital Image.

- Scipion Dupleix. The resoluer; or Curiosities of nature written in French by Scipio Du Plesis counseller and historiographer to the French King. Vsefull & pleasant for all. London: N. & I. Okes, [1635]. Call number: STC 7362.

What is Sleep? From the Medical to the Metaphorical

In The Anatomy of Melancholy, Robert Burton defined sleep as a “binding” of the senses. This “binding” was routinely described as the product of digestion, thought to be sleep’s primary cause. Medical writers asserted that fumes produced during digestion ascended from the stomach to the brain, where they impeded the passage of the “animal spirits” responsible for rational and sensory activity. At the same time, sleep had non-medical significance, lending itself to a variety of literary and allegorical interpretations.

Sleep was represented in a variety of literature of the day. Samuel Daniel’s influential sonnet sequence, Delia, features a poem addressed to “Care-charmer sleepe,” the most famous example of a sub-genre of poetry devoted to sleep. Other Elizabethans who wrote on this topic include Sir Philip Sidney and William Shakespeare.

Richard Braithwaite, an Oxford-educated poet and satirist, wrote a compendium of stories and aphorisms with a range of moralizing functions, from teaching moderation to scrutinizing fashion, but it takes its title—Art Asleep Husband? A boulster lecture—from the figure of a scolding wife “lecturing” her husband while he pretends to sleep.

Medical writers, like Somerset physician Tobias Venner, also had something to say about the benefits and detriments of certain sleep. Venner argues for the benefits of sleeping with one’s mouth open. He also stresses sleep’s link to “concoction,” or digestion, which he deems “the root of life.”

Items included

- Richard Brathwaite. Ar’t asleepe husband? London: R. Bishop, for R[ichard]. B[est]., 1640. Call number: STC 3555 and LUNA Digital Image.

To Make One Sleep

Judging from the large number of surviving manuscript recipes (or “receipts”) for insomnia, sleep disorders were as great a problem in early modern England as they are today. The ingredients in these recipes range from the unsurprising (poppies) to the somewhat puzzling (lettuce). However, the effectiveness of some ingredients lies in the perceived connection between physiology and the properties of the substance itself: lettuce, like sleep, was thought of as cold and wet, which is why it was believed to provoke sleep in the sleepless.

Mary Granville and her daughter Anne (Granville) Dewes include a recipe against insomnia in their receipt book—"To make one sleepe." The afflicted person is advised to wet two linen cloths with a mixture of strained ivy leaves and white wine vinegar, and then apply the cloths to the forehead and temples.

Another miscellany includes a recipe for “A Dormant Drink” designed to induce continuous sleep for two full days. For some reason, all of the ingredients’ names are written backwards (“yppop” for poppy, “ecittel” for lettice).

Mrs. Corlyon's receipt book contains the three following recipes: the first produces a “liquor” comprised of ingredients such as rose water, “Woemans milke,” and wine vinegar, to be applied to the forehead and temples. The second recipe is a drink made primarily of “White lettice seede” and sugar, to be followed by “a draft of posset ale” (milk curdled with ale). The third recipe consists of a warm drink of white poppy seed powder and posset ale made with violets, strawberry leaves, and “singfoyle” (cinquefoil).

Items included

- Grenville Family. Cookery and medicinal recipes of the Granville family. Manuscript, ca. 1640 – ca. 1750. Call number: V.a.430; displayed p.1.

- Historical extracts. Manuscript, ca. 1625. X.d.393; displayed leaf 34.

- Mrs. Corlyon. A booke of such medicines as have been approved by the speciall practize of Mrs. Corlyon. Manuscript, ca. 1606. Call number: V.a.388; displayed p. 18–19.

Herbals

Herbals provide physical descriptions of plants, with particular attention to their various medicinal virtues. Thus, they were an important resource for recipes. Recipes meant to provoke sleep might require mandrake or Indian dreamer, while those that roused the sufferer from sleep-related diseases such as lethargy might call for mustard plant.

This fanciful illustration is the mandrake, a plant whose root was taken to resemble the human form and which purportedly shrieked when removed from the ground. A narcotic plant, the mandrake’s effects were, in John Donne’s words, “betwixt sleep and poison.” Shakespeare references the mandrake’s soporific qualities in Othello and Anthony and Cleopatra.

The Indian Dreamer, which resembles hemp, was another plant used to cause sleep but can also “grow great dreamers according to their humours and dispositions….”

But, for those who had too much of sleep, other plant cures were available. Towards the end of an entry devoted to the mustard plant, Rembert Dodoens discusses “Lethargie or drowsie evill,” a disease in which people “cannot waken themselves.” He advises using a paste of mustard and figs to create heat, thus removing the cold humors that cause excess sleep.

Items included

- Ortus sanitatis: de herbis et plantis, de animalibus et reptilibus, de auibus et volatilibus, de piscibus et natatilibus, de lapidibus et in terre venis nascentibus, de vrinis et ea rum speciebus, tabula medicinalis cum directorio generali per omnes tractatus. Strasbourg: Johann Prüss, not after Oct. 21, 1497. Call number: INC H417 Copy 1 Massey and LUNA Digital Image.

Richard Haydock: The Sleeping Preacher

In 1605, a medical doctor named Richard Haydock attracted the attention of James I because of his ability to deliver brilliant sermons while in a deep sleep. Haydock had a passion for preaching, but ended up studying medicine instead because of a debilitating stutter. After inviting Haydock to court to hear the sleeping sermons himself, James I exposed Haydock as a fraud. However, because his sermons had been so pro-monarchy, his only punishment was publicly confessing his deceit. The prefatory material to Haydock’s treatise on dreams, Oneirologia, served as his confession.

To express his gratitude to the king for his leniency and to acknowledge his earlier deception, Haydock composed a treatise on dreams, and he dedicated his manuscript to King James. No doubt he hoped that James would be pleased to be referred to as a son of King Solomon, known for his wisdom, and that he would be interested in a text on dreams. Chapter four of Haydock’s work concentrates on what happens in the mind when the body is asleep. He assures his readers that when drowsy vapors take over common sense, fantasy must be freed or there will be no dreams. The manuscript was never published, and the copy at the Folger is the only copy known to exist.

The story of King James unmasking Haydock’s fraud was a popular one that appeared in many seventeenth-century histories, including Sir Richard Baker’s A Chronicle of the Kings of England. It was not only an interesting story in itself, but it also allowed historians to praise the king for his “admirable sagacity in discovering of Fictions.”

On this frontispiece, Richard Haydock (an artist as well as a preacher) has engraved a portrait of himself.

Items included

- Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo. A tracte containing the artes of curious paintinge carvinge & buildinge written first in Italian by Io: Paul Lomatius painter of Milan and Englished by R.H. student in physik. Oxford: Joseph Barnes for R[ichard] H[aydock], 1598. Call number: STC 16698 Copy 2 and LUNA Digital Image.

- Richard Haydock. Oneirologia, or, A briefe discourse of the nature of dreames. Manuscript, 1605. Call number: J.a.1 (5) and LUNA Digital Image

James I

James I was fascinated by strange phenomena and supernatural events. He wrote a treatise on witchcraft, but later became more interested in exposing fraudulent supernatural events, such as the sermons of Richard Haydock, “the sleeping preacher.” James I’s writings on dreams reveal a deep skepticism of their significance. In 1622, however, he felt quite differently when he had a dream that foretold his own death.

King James’s treatise on witchcraft, Daemonologie, includes a section on nightmares. Although he strongly believed in the power and danger of witches, he was far more skeptical about dreams. In this treatise, James claims that nightmares result from natural causes rather than from demons, or succubi.

King James also wrote the Basilikon Doron as an educational guide for his son Henry, Prince of Wales. In a section on sleep, he advises Henry to “take no heede to any of your dreames,” because prophecies and visions no longer occur. James believed those ceased with the coming of Christ.

Arthur Wilson's The history of Great Britain includes the story of James I and Richard Haydock, the “Sleeping Preacher,” as the prime example of “brutish imposters” exposed by the king’s reason. Wilson also shared James’ belief that dreams are not supernatural, stating in the preface that he is “not like one in a Dream, who starts at the horror of the Object which his own imagination creates.”

Items included

- James I. Daemonologie, in forme of a dialogue. Edinburgh: Robert Walde-graue, 1597. Call number: STC 14364 and LUNA Digital Image.

- James I. The workes of the most high and mightie prince, James by the grace of God King of Great Britaine, France and Ireland, defender of the faith, &c. London: Robert Barker and John Bill, 1616. Call number: STC 14344 Copy 1 and LUNA Digital Image.

Definitions of Dreams

Beliefs about dreams were wide-ranging: while some people believed dreams were simply the fragments of the day retold or the result of food or drink partaken, others thought dreams were an expression of guilt over an action taken or considered, or were influenced by a person’s dominant humor. Many people believed that dreams came directly from God, angels, or demons and that they exposed a person’s character as virtuous or venal.

Dreams could be divided into three categories: divine, supernatural, and natural and they were thought to foretell the future. Many were convinced that if they could unlock the meaning of dreams, they could know the future.

Wilhelm Scribonius defines a dream as “an inward act of the mind” while the body is sleeping. The soul creates dreams from the spirits of the brain, and the most pleasant dreams come as morning approaches, when the spirits are most pure.

William Vaughan writes about both sleep and dreams in his treatise on personal health. He warns of the dangers of sleeping at noon and observes that dreams could either be a remembrance of the past or “significants of things to come.”

Thomas Cooper argues that some dreams are natural and might inform us “of the sinnes of the heart,” since what we think or do during the day returns as dreams at night. But he is most concerned with dreams that came from God—moving us toward true worship—and Satan, who puts into the brain “Divellish Dreames” hoping to turn us toward evil.

In a very popular text which he revised throughout his life, Owen Felltham argues that the best use someone can make of their dreams is to gain greater self-understanding. The mind continues to work even in the depths of sleep, and dreams show us our inclinations.

Dream Interpretation

A range of early modern books offered dream interpretation, and physicians or astrologers would frequently interpret dreams for payment. Scholars such as Thomas Hill, Marc de Vulson, and Richard Saunders studied ancient dream treatises, especially Oneirocritica, composed by Artemidorus about 200CE, in order to understand the symbolism of dreams. Their interpretations varied widely, and meanings were based not only on the subject matter of the dream, but also on the dreamer’s gender, social status, dominant humor, or profession, as well as the time of year or night the dream was had.

Thomas Hill’s text was very popular in Renaissance England, succinctly explaining the meanings of hundreds of dreams. For example, to dream of picking green apples from a tree meant good fortune, while dreaming of drinking thinned mustard meant one would be accused of murder.

Philip Goodwin’s book provides a guide for interpreting the mysterious divine and demonic visitations that a person might experience while sleeping and dreaming. He also advocates prayer before sleeping and after waking, and suggests that shorter stretches of sleep may bring better dreams.

Marc de Vulson believed that dreams could be both instructional and amusing. He argues that since true events are foretold in dreams, it would be foolish to ignore them. He explains what dreams about plays and pastimes mean. For example, dreaming you see a comedy on stage foretells success; dreaming of a tragedy means “grief and affliction.”

Richard Saunders believed that the same dream had different meanings depending on a person’s dominant humor and the time of year. Thus, during the third phase of Leo (mid-August), dreaming one was “stark naked in a Church” would be a bad dream for a person of sanguine humor but a good dream for a melancholic person.

Items included

- John Dee. Engraving, [London, England]: Hunt & Clarke, 1827. Call number: ART File D311 no.1 (size XS) and LUNA Digital Image.

- Thomas Hill. The moste pleasaunte arte of the interpretacion of dreames, whereunto is annexed sundry problemes with apte aunsweares neare agreeing to the matter, and very rare examples, not the like the extant in the English tongue. London: Thomas Marsh, 1576. Call number: STC 13498 and LUNA Digital Image.

- Philip Goodwin. The mystery of dreames, historically discoursed; or A treatise; wherein is clearly discovered, the secret yet certain good or evil, the inconsidered and yet assured truth or falsity, virtue or vanity, misery or mercy, of mens differing dreames. London: A.M. for Francis Tyton, 1658. Call number: 157- 690q

- Marc de Vulson. The court of curiositie. London: J[ames]. C[ottrell]. for William Crooke, 1669. Call number: 165-039q.

- Richard Saunders. Saunders physiognomie, and chiromancie, metoposcopie, the symmetrical proportions and signal moles of the body, fully and accurately explained; with their natural-predictive significations both to men and women. being delightful and profitable: with the subject of dreams made plain: whereunto is added the art of memory. London: H. Brugis, for Nathaniel Brook, 1671. Call number: S755 and LUNA Digital Image.

Dream Control

While some people believed dreams could be regulated through prayer or a healthy diet, others had more elaborate methods for controlling them. These included such strategies as wearing certain kinds of gemstones or imbibing potions with fanciful components such as dragon’s tongue, or rubbing one’s temples with lapwing’s blood. The desire to avoid nightmares, or “terrors of the night,”led to the circulation of these recipes in manuscript.

Thomas Nichols’s lapidary, or book on gemstones, explains how specific stones can affect dreams. For example, he shares reports that wearing a ruby in an amulet or drinking ground-up rubies will drive away “terrible dreams” as well as sadness, evil thoughts, and evil spirits. It was a widely held belief that gemstones could help control dreams. Wearing a crystal or ruby around one’s neck prevented nightmares. Children were advised to wear emeralds to avoid nightmares. Wearing an amethyst caused exciting dreams and prevented drunkenness. And wearing an onyx to bed caused the wearer to dream of a departed friend.

Plants, as we've seen throughout the exhibition, were used for many medicinal purposes, and controlling dreams was yet another way to use them. Nicholas Culpeper composed a directory of over three hundred plants, and it includes several that could control dreams. One entry describes polypody, a variety of fern thought to be most medicinally powerful when it grows on oak stumps or trunks. Drinking liquid distilled from its roots and leaves prevents “fearful or troublesome sleeps or dreams.”

A very popular book with cures and recipes for a wide range of ailments, from how to heal ringworm to how to “make the haire fall off” was The secrets of Alexis. One recipe explains how to see wild beasts in a dream; it also includes a number of recipes for inducing sleep.

Various animal parts were used in recipes in much the same way as plants or gemstones. Edward Topsell's Historie of serpents is a spectacularly illustrated and hand-colored book, devoted to serpents (including dragons). According to Topsell, eating the wine-soaked tongue or gall of a dragon could prevent nightmares.

Items included

- Thomas Nicols. A lapidary: or, The history of pretious stones: with cautions for the undeceiving of all those that deal with pretious stones. Cambridge: Printed by Thomas Buck, 1652. Call number: 154-179q.

- Nicholas Culpeper. The English physician enlarged; with three hundred sixty and nine medicines, made of English herbs, that were not in any impression until this. Being an astrologo-physical discourse of the vulgar herbs of this nation; containing a compleat method of physick, whereby a man may preserve his body in health, or cure himself, being sick, for three pence charge, with such things only as grow in England, they being most fit for English bodies. London, 1698. Call number: C7512.2.

- Alessio Piemontese. The secrets of Alexis: containing many excellent remedies against diuers diseases, wounds, and other accidents. With the maner to make distillations, parfumes, confitures, dyings, colours, fusions, and meltings. .... Translation by William Ward (parts 1-3) and Richard Androse (part 4) of a French version. London: William Stansby for Richard Meighen and Thomas Jones, 1615. Call number: STC 299 and Binding image on LUNA.

- Edward Topsell. The historie of serpents. London: William Jaggard, 1608. Call number: STC 24124 Copy 2 and LUNA Digital Image.

Nightmares

A dream called “the Mare” was specifically described by Nicholas Culpeper “as when someone was sleeping to feel an uncommon oppression or weight about his breast or stomach, which he can be no means shake off. He groans, and sometimes cries out, though oftener he attempts to speak, but in vain.” Sleepers often believed that a demon—a succubus or an incubus—had visited them in their sleep in an attempt to breach their chastity. It was said that those of a melancholy humor often had frightening dreams of dark places, falls from high turrets, and furious beasts. Nightmares and ominous dreams are used to great dramatic effect in plays such as Shakespeare’s Richard III.

Act I of Shakespeare’s Richard III ends with the murder of the Duke of Clarence, presaged by the dream of drowning he recounts at the start of the scene. Here, just as the dream is about to end, howling fiends seize the terrified Clarence to take him to hell.

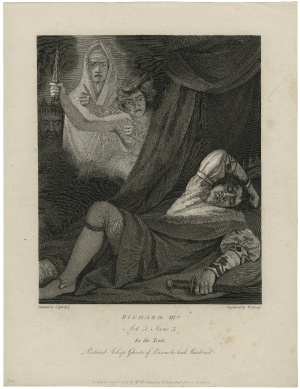

In the same play, Richard III has a troubled sleep on the eve of the Battle of Bosworth Field. Visited by the ghosts of those whose deaths he caused, he dreams the battle is in progress. As the last ghost leaves, he awakens with a start shouting “Give me another horse; bind up my wounds. Have mercy, Jesu!”

Thomas Tryon believed that dreams of demonic visitations like Richard III's were caused by sleeping on one’s back, eating heavy suppers just before bed, and drinking spirits in excess. He suggests that nightmares could be avoided by sleeping on one’s side and eating a healthier diet.

Thomas Nash argues that dreams are based on thoughts and experiences that happen over the course of the day: “A dream is nothing else but a bubbling scum or froth of the fancy, which the day hath left undigested.” As for nightmares, Nash claims they are the result of guilty feelings. For example, the dreadful sins of treason and murder would cause terrible dreams.

Physician Jacques Ferrand wrote a book on the causes, symptoms, and cures of “Love, or Erotique Melancholy.” Ferrand describes terrifying instances of people, mostly women, who believe that they were raped by the devil in their sleep, “when as in truth they were only troubled with the Nightmare.”

Items included

- James Neagle after Thomas Stothard. King Richard III, act 1, sc. 4. Engraving, London: Geo. Kearsley, 1804. Call number: ART File S528k8 no.8 (size XS) and LUNA Digital Image.

- William Sharp after John Opie. Richard IIID., Act 5 Scene 3, in the tent, Richard asleep, ghosts of persons he had murdered. Engraving, London: Mr. Woodmason, 1794. Call number: ART File S528k8 no.80 (size M) and LUNA Digital Image.

- Jacques Ferrand. Erotomania or A treatise discoursing of the essence, causes, symptomes, prognosticks, and cure of love, or erotique melancholy. Oxford: L. Lichfield, 1640. Call number: STC 10829 and LUNA Digital Image.

Supernatural and Divine Dreams

Martyrs in both Catholic and Protestant martyrologies, including John Foxe’s Actes and Monuments, were often portrayed as having prophetic dreams. It was also believed that angels regularly visited people in their dreams, and a frequent narrative technique to give a text authenticity was to describe how the author was sleeping when visited in a dream by divine beings who encouraged the writing of their work.

In 1556, Agnes Potten was sentenced to be burned for heresy, a victim of the persecutions of Protestants under Mary I. John Foxe relates in his book of martyrs that, the night before her death, she had a foretelling dream in which she “saw a bright burning fyre, ryght up as a pole, and on the syde of the fire she thought there stoode a number of Q[ueen] Maries friendes looking on.”

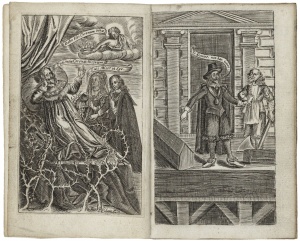

Other penned prophetic dreams are less dire: In The book of the city of ladies, Christine de Pisan, who made her living as an author prior to the printing press, writes that she was inspired by a dream to build an allegorical city honoring women. In a fifteenth-century French manuscript copy of her masterpiece, on loan from The Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Christine is depicted being pulled out of bed by the three female virtues—Reason, Rectitude, and Justice—who assist her in building her city.

In his poetical work, The hierarchie of the blessed angels, the playwright Thomas Heywood writes about the many properties of angels, one being their ability to enter a dream and help a good Christian find the right path in the waking life.

Items included

- John Foxe. Actes and Monuments of matters most speciall and memorable. London: Peter Short, 1596. Call number: STC 11226 copy 3 and LUNA Digital Image.

- LOAN from Rare Books and Manuscripts Department, The Trustees of the Boston Public Library, MA. Christine, de Pisan. The book of the city of ladies. France, 1405. BPL call number: Ms.f.Med.101 and Internet Archive.

- Thomas Heywood. The hierarchie of the blessed angells. London: Adam Islip, 1635. Call number: STC 13327 and LUNA Digital Image.

Political Dreams

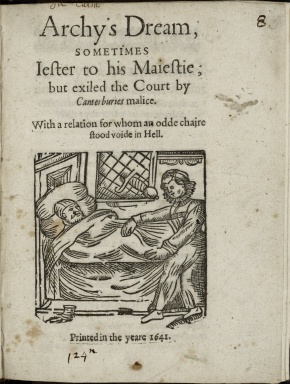

Religion and politics were deeply intertwined in Renaissance England. The threats to sixteenth-century Protestants in Mary I’s reign were dramatized in “dream” scenes in plays about such politically significant characters as Princess Elizabeth (the future queen) and Katherine, Dowager Duchess of Suffolk. In the seventeenth century, the struggles between Royalists who supported Charles I and Parliamentarians were described in dreams in a series of political pamphlets.

John Quarles writes in couplets about his dream of the 1649 execution of Charles I. The images at the beginning of his poem show Charles the night before his death dreaming of his wife and son while an angel prepares to replace the crown he lost on earth with a heavenly one. Opposite this, we see the stark reality of Charles about to be executed.

In his dramatization of the dangers experienced by the Protestant Princess Elizabeth in the reign of her Catholic half-sister Mary, Thomas Heywood includes “a dumb show” (a scene played silently) while Elizabeth sleeps. In the dumb show, angels stop the villain Winchester from killing the sleeping princess and place a Bible in her hands. Elizabeth wakes, as if from a dream, not knowing how the Bible materialized.

After the execution of Charles I in 1649, his son Charles sought help in Scotland to claim the throne. According to James Douglas, the young Charles dreamt he saw a spider with a crown hanging over its head and two other crowns at the end of the thread. As the spider lowered itself down the cobweb, it fell and lost everything. Despite the dire portent of this dream, Charles II was restored as king in 1660.

Items included

- John Quarles. Regale lectum miseriæ: or, A kingly bed of miserie. In which is contained, a dreame: with an elegie upon the martyrdome of Charls, late King of England, of blessed memory: and another upon the Right Honourable, the Lord Capel. London, 1649. Call number: 157-844q and LUNA Digital Image

- Thomas Heywood. If you know not me, you know no bodie: or, The troubles of Queene Elizabeth. London, 1605. Call number: STC 13328; displayed title page.

Arise for It Is Day

From rinsing out one’s mouth to throwing open the windows to air out a stuffy bedchamber, rituals for waking were as common as rituals for going to sleep, and a new day was often welcomed with prayer. The renewal inherent in the daily cycle seemed an inspiration for many: the printer John Day took as his printer’s device a sunrise scene and the phrase “Arise for It Is Day” (punning off of his own name), while many authors celebrated the new day with carpe diem verses and morning songs, or aubades.

“Get up, get up for shame” begins Robert Herrick’s famous “carpe diem” (seize the day) poem, as the speaker tries to rouse his “sweet-Slug-a-bed.” While Corinna stays in bed, youths rejoice in May Day revelry, exchanging flirtatious glances, playing kissing games, and rolling in the grass until plain gowns become green.

Thomas Tryon, who had prescriptions for how to sleep, also wrote on waking and health, and was particularly concerned with preventing the “generation of bugs”—a common household problem. Tryon advises that “there is nothing better…than every Morning when you rise to set open your Windows, and lay open your Bed-cloaths.” He believed this would release “the gross humid Steams” from the bed and would prevent fleas and other bugs from breeding.

John Evans, the compiler of a literary commonplace book, devotes a column to the topic “Awake,” “Awaked,” and “Awaking.” He provides quotations from eight different sources, including two Shakespeare plays (Henry IV, pt. 2 and Julius Caesar). Two extracts are from Francis Quarles’ Emblems and three extracts are from a song in Cosmo Manuche’s The Bastard, a play published in 1652.

Items included

- William Tyndale. The whole workes of W. Tyndall, John Frith, and Doct. Barnes, three worthy martyrs, and principall teachers of this Churche of England, collected and compiled in one tome togither, beyng before scattered, and now in print here exhibited to the Church. London: John Day, 1573. Call number: STC 24436 Copy 1 and LUNA Digital Image.

- Robert Herrick. Hesperides: or, The vvorks both humane & divine of Robert Herrick Esq. London, 1648. Call number: H1596 and LUNA Digital Image.

- John Evans. Hesperides, or, The Muses garden. Manuscript, ca. 1655-1659. Call number: V.b.93 and LUNA Digital Image.

Additional items exhibited

- Hortus sanitatis. London, 1536. Call number: QH41 H48 1536 Cage and LUNA Digital Image.

- Replica early 17th-century man's night shirt. Linen with blackwork embroidery. By Emma Lehman, 2008, based on an original in the Fashion Museum, Bath.

- The New Testament of ovr Lord Iesvs Christ. Translated out of the Greeke by Theod. Beza, and Englished by L. Tomson. Bound with: The whole booke of Psalmes: collected into English meeter by T. Sternhold, I. Hopkins, W. Whittingham, and others, conferred with the Hebrew, with apt notes to sing them withall. Newly set foorth, and allowed to be sung in all churches, of all the people together, before and after morning and euening prayer, as also before and after sermons. Moreouer in priuate houses, for their godly solace and comfort, laying apart all vngodly songs and ballads, which tend onely to the nourishing of vice, and corrupting of youth. London: Robert Barker, ca. 1610. Call number: STC 2907 and LUNA Digital Image and Binding image on LUNA.

- Richard Brathwaite. The English gentlewoman, drawne out to the full body: expressing, what habilliments doe best attire her, what ornaments doe best adorne her, what complements doe best accomplish her. London: B. Alsop and T. Favvcet, for Michaell Sparke, 1631. Call number: STC 3565 and LUNA Digital Image.

- Rembert Dodoens. A niewe herball, or historie of plantes: wherein is contayned the whole discourse and perfect description of all sortes of herbs and plantes. London: Henry Loë, 1578. Call number: STC 6984 Copy 1 and LUNA Digital Image.

- Thomas Walkington. The optick glasse of humors or The touchstone of a golden temperature, or the Philosophers stone to make a golden temper. Oxford: W[illiam]. T[urner], 1631?. Call number: STC 24968 and LUNA Digital Image.

- George Gower. The Plimpton "Sieve" Portrait of Queen Elizabeth I. Oil on panel, 1579. Call number: ART 246171 (framed) and LUNA Digital Image.

- Archie Armstrong. Archy’s dream. London, 1641. Call number: A3708 and LUNA Digital Image.

- Beroaldo. Le Tableav des Riches Inventions. 1600. Call number: PQ4619.C9 F8 1600 Cage and LUNA Digital Image.

Supplemental material

To Sleep, Perchance to Dream children's exhibition

To Sleep, Perchance to Dream family guide

Lying In

Listen to exhibitions manager Caryn Lazzuri discuss one specific use for the bedchamber.

- John Geninges. The life and death of Mr. Edmund Geninges priest, crowned with martyrdome at London, the 10. day of November, in the yeare M.D.XCI. 1614. Call number: STC 11728 Copy 2 and LUNA Digital Image.

A Counterfeit Death

Listen to co-curator Garrett Sullivan discuss the title page of Walter Raleigh's History of the World.

- Walter Raleigh. The discoverie of the large, rich, and bewtiful empire of Guiana, with a relation of the great and golden citie of Manoa (which the Spanyards call El Dorado) and the provinces of Emeria, Arromaia, Amapaia, and other countries, with their rivers, adjoyning. London: Robert Robinson, 1596. Call number: STC 20634 Copy 1 and LUNA Digital Image.

- Walter Raleigh. The history of the world. London: [William Stansby] for Walter Burre, 1614. Call number: STC 20637 and LUNA Digital Image.

Satan and the Sleeping Eve

- John Milton. Paradise lost. A poem in twelve books. London: Miles Flesher, 1688. Call number: M2147 and LUNA Digital Image.

Video

Scholars Garrett Sullivan and Carole Levin discuss what at Elizabethan bedchamber may have been like.

Trouble falling asleep is nothing new. Exhibition curator Carole Levine talks about DIY Elizabethan remedies for insomnia.