Setting the Medieval Stage

This article is the second of three installments of the Ten Performance-Based Lesson Plans for Medieval Theatre, as noted in the article Medieval Drama and Performance-Based Pedagogy, conceived and written by Barbara J. Bono, Maria S. Horne, and Michelle Markey Butler, and is associated with the Folger Institute's 2016-2017 year-long colloquium on Teaching Medieval Drama and Performance, which welcomed advanced scholars whose research and pedagogical practice explore historical, literary, and theoretical dimensions of medieval drama from the perspective of performance.

As the Setting the Medieval Stage title name suggests, this article focuses on a series of three performance-based lesson plans for Medieval Theatre to help create a space in which to perform medieval drama.

Continue on to Performing Medieval Drama: Audiences, Communities, and Adaptations: Lesson Plans 8 through 10.

Go back to Verba et Res/Words and Things: The Speaking Picture of Medieval Drama: Lesson Plans 1 through 4.

Lesson Plans 5 through 7 for Medieval Drama and Performance-Based Pedagogy

Below we supply a a series of three performance-based Lesson Plans for Medieval Drama, which consider the symbolic shape of an action in medieval drama.

The spaces of medieval drama were various, labile, and indeed often mobile. The York Biblical cycle plays processed annually on pageant carts into and about the city to stop at York Minster and end on the market Pavement; small travelling companies acted other plays, performing in open spaces, inn yards, or great houses. Later, as plays retreated into manuscript, they might have been brought out for occasional declamation.

Plays of such sharp moment and open engagement could, in theory, take place anywhere on this middle earth. As Peter Brook famously began his 1968 classic, The Empty Space, “I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage. A man walks across this empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and that is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged,” and modern revivals of medieval plays have utilized halls, cloisters, hillsides, city plazas and streetscapes, as well as more formal stages.

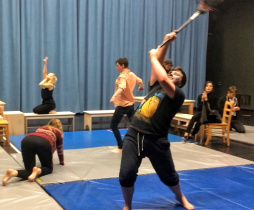

These three Lesson Plans encourage you to find a suitable space for your play exercises, from a classroom with the desks pushed back to the more formal stage to

the outdoor green space which might draw in community passers-by. Then we offer you a selection of monologues and especially powerful scenes to help develop the craft of your ensemble.

Lesson Plan 5: Stages for medieval drama

What’s On for Today and Why?

A discussion and ideally also a series of site-visitations of likely campus or community sites for a modern performance of your play texts.

What to Do?

Have the students read over the section on Staging Medieval Drama, including the links, in advance of class. Then in class have them get up and illustrate—through on-the-board drawings or the positioning their own bodies—the nature of pageant, place-and-scaffold and hall play stagings.

Discuss how best to adapt their plays to staging in this particular classroom, and what alternative sites might be available on campus and in the community. If there are time and resources, explore some of these alternative sites either in the flesh or virtually.

How’d It Go?

Students should begin to get a sense of the spaces in which their words will be articulated and their bodies will move. Send them home to begin to sketch some of the key moments or tableau vivant for your chosen play(s), complete with props and costumes, within some of these potential spaces.

Lesson Plan 6: Filling the space. Medieval monologues and the power of words

What’s On for Today and Why?

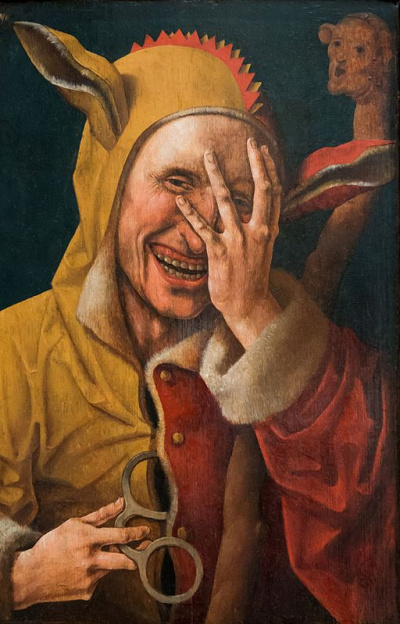

Professional actors audition all of the time by preparing and presenting powerful and nuanced monologues. Medieval drama offers many such opportunities, and often little-known gems. These monologues are not primarily motivated by an individual self or character; instead they are also expressions of a creatural position within a theological and social system in which the audience likewise is bound.

Our exercises to date in voice, vocabulary, objects, position, relation, costuming and place have been steps in preparation for some degree of that historical understanding. We have compiled a list of outstanding medieval monologues from the canon of medieval plays, and by now you should be aware of other passages derived from your own readings. Choose several, and have your students begin to prepare them for presentation.

What to Do?

Have your students chose a monologue of their choice from the supplied list of striking monologues from medieval plays or from the plays you have been reading in class. Being able to choose their own monologue will help students to develop a sense of ownership over the material they are to perform.

Once the text has been selected, they will prepare their monologue for in-class performance, critique and discussion. Ask them to start working on their piece, applying what they have learned in the previous classes (see Lessons 1-5) and also from their own research as well as acting technique: make sure they read the text out loud, make strong choices (asking who, what, where, when, why, etc.), and stand the text up for performance presentation.

To maximize class time, you may choose to split the group into pairs, and have the students first practice back and forth with each other, making sure that they use full vocalization and that their physical expression is connected to their voice, the text, and given circumstances. The teacher should be actively engaged at this stage, possibly circulating throughout the room, encouraging the student pairs in their work.

At least one class session should be devoted to rehearsal and another one to giving each student the opportunity to perform his or her monologue for the entire group, followed by a discussion and critique of the work, with the objective of advancing ideas on how to better perform it next time around. At home students should rehearse while applying the verbal “notes” (the observations and critiques of their classmates) they have received in class, as well as aiming toward getting their monologue “off book” (memorized).

Even a preliminary approach to this intensive practice may take more than one class session. Keep in mind that this work should be process-oriented rather than final product-driven.

How’d It Go?

Students should begin to have a sense of the verbal force and physicality of entire climactic or turning point moments within these dramas, and should begin to be comfortable working with each other toward this realization and critiquing each other’s presentations.

Lesson Plan 7: Creating and inhabiting the space. Scenes from medieval drama

What’s On for Today and Why?

Actors work on scenes to develop and perfect their acting tools, while also expanding their creativity and range. Medieval drama provides an exceptional vehicle for exploration of the range and scope of human action, and allows actors to utilize a variety of acting techniques, genres, and styles. These texts are a great tool to break free from ingrained conventions and a source for the rediscovery of deep potentialities of thoroughly motivated and embodied symbolic actions. Have your students stretch their sense of what is possible on the stage by beginning to stage some powerful scenes.

What to Do?

Have your students choose a scene from our list of challenging scenes from medieval plays, for acting classes or another from the plays you have been reading. Students working in pairs or clusters should then tackle this scene work from the standpoint of the total dramatic action in which the scenes are embedded, and should begin by creating place, both physical and sensory.

Ask them to consider basic questions such as: Where does this action take place? How is it being performed? Where is the audience in relationship to the action? etc. These answers will invariably affect the physical life of the action on the stage (e.g. entrances and exits, stage directions, the use of the acting space, etc.).

You may also choose to follow the same dynamics described in Lesson Six, including working on these scenes within the framework of more general, not exclusively medieval, acting and performance classes. Either way, encourage your students to be inventive and to explore not just a classical or naturalistic rendition of the action but rather to approach their scene work from a variety of possible modalities (such as collective creation, devised performance, experimental theater, interdisciplinarity, intermediality, viewpoints, and many other theatrical techniques).

How’d It Go?

Students should begin to have a sense of the embodied force of entire climactic or turning point moments within these dramas, and should begin to engage and work with each other toward this realization as they critique each other’s presentations.

Continue on to Performing Medieval Drama: Audiences, Communities, and Adaptations: Lesson Plans 8 through 10.

Go back to Verba et Res/Words and Things: The Speaking Picture of Medieval Drama: Lesson Plans 1 through 4.

Go to Medieval Drama and Performance-Based Pedagogy.

Page written by

Barbara J. Bono, University at Buffalo, SUNY

Maria S. Horne, University at Buffalo, SUNY

Michelle Markey Butler, University of Maryland