Medieval Drama: Staging Contexts

This article is associated with the Folger Institute's 2016-2017 year-long colloquium on Teaching Medieval Drama and Performance, which welcomed advanced scholars whose research and pedagogical practice explore historical, literary, and theoretical dimensions of medieval drama from the perspective of performance.

| Some Useful Terms | |

|---|---|

| Processional staging | The movement of pageant wagons along a route, stopping at pre-determined points to put on the play. Processional staging puts on the same dramatic work multiple times in different locations. |

| Pageant wagons | Large, wheeled platforms (the numbers usually given are roughly 6' by 12'), often quite ornate, that were used in the civic cycles to move between stations. |

| Locus | An identified and defined area for performance, often marked by a structure or raised platform upon which the performance occurs. Also referred to as scaffold. |

| Platea | Undefined and undifferentiated performance space, such as the area around a pageant wagon or the space between the scaffolds in a locus-and-platea play. Also referred to as place. |

| Great hall | The main room of a large aristocratic, guild, or manor house, generally one and a half to three times as long as it was wide. It could be used for multiple purposes, but in the context of drama served as the venue for plays and other entertainments. |

| Dumbshows | Mimed performances intended to convey and summarize an action for the audience. |

| Mummings and Disguisings | Dramatic performances wherein the performers would hide their identities completely and take on roles as mythological or allegorical figures. These could either be formal in nature, similar to a masque, or be a more free-form folk performance. |

Thinking about the staging of medieval drama requires us to consider it as a living thing to be experienced, rather than as simple "dead" text on a page, safely anthologized and cut off from our daily lives. It provides us the opportunity to understand not just the plays themselves, but also the authors, performers, and viewers of these plays as tied into their communities. Medieval drama often centered on occasions such as festivals, saint's days and other religious observances, the entry of important people into cities, as part of what we'd think of as street performance today, and as a mealtime entertainment. Although incredibly sophisticated, it is not "professional" in the ways that we consider Shakespeare and his London contemporaries to have been. Recovering and understanding the likely staging practices of late medieval and early Tudor drama is thus a challenge - we have to rethink our expectations and unlearn much of what we assume regarding the production and viewing of plays - but these investigations also offer an opportunity to understand how medieval people expressed their social, religious, and political concerns through performance.

Medieval drama as it exists in the surviving texts is not the entirety of dramatic performance as it occurred during the medieval period. Non-scripted performances in churchyards and ritual ceremonies - such as the Quem Quaeritis ceremony attached to the Easter liturgy; church ales, summer games, and other fundraising activities; Lords of Misrule; Robin Hood games; Morris Dances; and what we would think of today as street theatre - all had their place in the dramatic practice of the Middle Ages. Although little evidence of such performances survives, they would have formed a lively and important part of what people in the Middle Ages considered "drama."

Types of Staging

Medieval dramatic texts that have survived in manuscript tend to fall into one of three basic types of staging, but these should not be taken as dogmatic or rigid categories meant to define what is or is not drama. Both the folk theatre mentioned above and more formal events such as the entry of Henry VI into London in 1432 had a strongly dramatic element; these performances might be best considered as mummings, disguisings, or dumbshows.

Civic Cycles

The outdoor, multi-episode civic cycles were performed using processional staging. There, pageant wagons - single or multiple-story wheeled platforms - moved between the set locations, or stations, at which each play was to be performed over the course of the processional route. The route itself wound through the streets of a city such a York, Chester or Coventry.

Each play in a civic cycle would have been the responsibility of one of the city's guilds. These groups of artisans or merchants controlled the practice of their craft in the city, and their participation in the civic cycles was seen as a type of communal duty. They were responsible for funding their individual performance as well as the maintenance of the pageant wagon and any stage properties. They were also tasked with finding individuals, often from among their membership, to perform the play.

Much of our evidence of the contemporary aspects of producing these cycle plays for performance comes from the accounts of these guilds, and are available through the Records of Early English Drama project. The records provided by REED and other sources have been used to inform modern, academic performances of medieval English civic drama. Recent performances of the York Crucifixion, for example, show how both the pageant wagon and the space around it could be utilized in performance by having the work of "nailing" Christ to the cross occur at ground level, but the cross is then placed into a prepared slot on the wagon itself. Similarly, the 2010 performance in Toronto of the Chester Fall of Man by Purdue University's MARS Players shows how a multi-level pageant wagon could be used in combination with the space around it, and the performance of Balaam and Balaak by actors from Duquesne University shows how medieval drama's use of space subverts the expectations of a modern theatergoing audience by having the characters move through the audience to take advantage of the stairs present at the station.

Place-and-Scaffold (or Locus-and-platea)

Place-and-scaffold plays tended not to rely on the same city setting as the civic cycles, and thus could be found within or just outside of the walled cities of the medieval period as well as in less urban areas. Based on the surviving manuscripts, they tend to be commonly associated with East Anglia and Cornwall. Instead of employing individual pageant wagons, the performance space was marked with multiple scaffolds, each one of which represented a concrete location in the narrative of the play. The space between them, or "place," was undifferentiated and could take on multiple roles as needed over the course of the play.

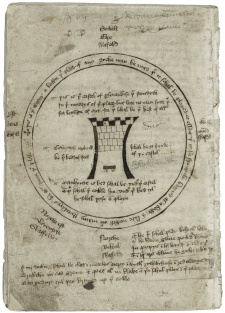

The place-and-scaffold play is also the type for which we have representative contemporary staging diagrams. Both the Cornish Ordinalia (MS. Bodleian 791 f.83r), a group of late fourteenth-century biblical dramas from Cornwall, and the East Anglian Castle of Perseverance (Folger MS V.a.354 f.191v) provide diagrams indicating the layout of scaffolds for performance.

Rather than having fixed or semi-fixed viewing positions, as occurs in modern proscenium staging or even the thrust staging of Shakespeare's Globe, audience members would have moved about the place, turning and positioning themselves to best view the action on a particular scaffold at any given time.

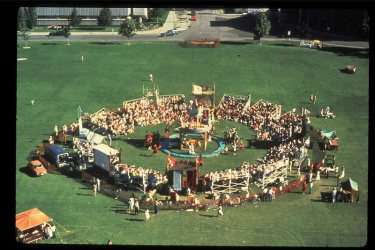

Perhaps the quintessential example of a place-and-scaffold play, the East Anglian Castle of Perseverance consists of five scaffolds associated with allegorical or biblical figures and the titular castle in the center. Modern academic productions of the play, such as the 1979 Poculi Ludique Societas performance at Toronto, have attempted to follow the example of the diagram provided in the manuscript. Similarly, the 2003 PLS performance of the Digby Mary Magdalene takes many of its cues from the Perseverance diagram but simplifies much of the description given in the manuscript of the play.

One thing that remains an abstraction in reading the play but becomes a matter of utmost concern in performance is the location and positioning of the audience. Academic performances like the 2010 performance of the Digby Conversion of St. Paul at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and the 1981 PLS performance of the N-Town Passion stress just how these plays don't quite fit modern assumptions of a largely sedentary and passive audience. Instead, they assume an audience will direct not only their attention, but also their bodies to following the performance.

Hall Plays

Unlike the civic cycles and place-and-scaffold plays, which were intended for public performance and consumption, the hall play is a product of and for the civic, religious, and aristocratic elites. Whereas the civic cycles and place-and-scaffold plays are performed outdoors, the hall play - as the name suggests - is performed indoors in the great hall of a guild, college, or aristocratic household, generally as part of the entertainments for particular occasions. Because these plays were written as occasional entertainments for the elites, the names of their authors are more likely to be known to us whereas the civic or place-and-scaffold plays remain anonymous.

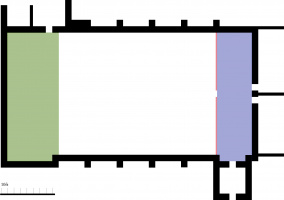

A rough floorplan of the Great Hall of Lambeth Palace (the medieval original was destroyed in the English Civil War and rebuilt after the Restoration). The green area is the dais, a raised area where the most important personages would sit, the blue area is the servant's or screens passage, and the red area represents the screen itself. A and B would likely have entered originally through the opening in the screen.

As occasional, one-off performances, hall plays also tended to reflect the construction of the venue in both their staging and their narrative. As they were produced to be performed in their intended venue only a few times at best, hall plays enjoyed a lively aftermarket in printed copies, and they were adapted and performed by itinerant troupes. As such, as the Database of Early English Playbooks attests the paratextual information for late fifteenth to early seventeenth-century print editions of these plays sometimes indicate not only a list of characters and the matter of the play, but also how many people are necessary to perform them.

Henry Medwall's Fulgens and Lucrese (c. 1497), an interlude written for performance at Lambeth Palace - then the residence of John Morton, the Archbishop of Canterbury - exemplifies these dramas performed in private halls. It is deliberately written as a dinner entertainment, with the characters of A and B emerging from the dinner guests and servants and setting the stage for the play. The dramatic narrative also makes use of the doorways into and out of the hall; at several points in the play, characters take advantage of the particular construction of the palace's great hall.

Plays like Medwall's Nature (late 15th or early 16th century) and John Skelton's Magnificence (c. 1529) are moral interludes written for staging in a great hall, with characters that exemplify traits like Nature, Reason, Innocence, Felicity, and Liberty. In this they are similar to both the allegorical aspects of the more explicitly Biblical cycle and place-and-scaffold plays as well as Elizabethan stage plays like Robert Wilson's Three Ladies of London (1584).

The features of these modes of staging late medieval drama were not discrete, and their techniques can easily overlap. For example, the concept of undifferentiated performance space represented by the "place" could be and most likely was used by characters in the civic cycles by the simple expedient of stepping off of the pageant wagon into the natural space occupied by the viewing audience.

Stage Directions and "Stage Directions"

Stage directions in medieval drama appear/are written in Latin, English, or a mix of the two - a result of the aggregate nature of medieval dramatic works. Where they are present, they do not appear as frequently as they do in early modern or modern plays. Stage directions in medieval drama manuscripts generally serve as a short note indicating an action a character should take - for example, a direction in the Digby Mary Magdalene that provides for the messenger figure to "go" or "come" to Herod, Pilate, and the Emperor; the indication of points where the characters are to "dicat", or "speak", in the Chester Trial; and the command for the angel to "descend" from heaven and "go" to heaven again in the N-town Joachim and Anna. Where medieval dramatic stage directions do not indicate an action, they may describe aspects of a character's dress, which can then be correlated against guild and civic records and give us a better understanding of the costuming of characters in these plays.

Stage directions in medieval drama manuscripts can also perform other functions. At times, they serve not to direct the action on the stage, but provide a summary description, letting a reader (or director or performer) know what actions are coming up in the play's narrative. For example, in the Digby Mary Magdalene, stage directions announce the entrance of the vice figures and the Good and Bad Angels but the characters do not actually appear at this time; instead, individual directions indicating the entrances of characters are repeated as the narrative of the Magdalene's seduction plays out.

Stage Design and Costuming

The Triumph of Archduchess Isabella by Denys van Alsloot. Depicting Archduchess Isabella as the queen of a procession honoring the crossbowmen guild of Brussels, the size and ornate decoration of the wagons are similar to how scholars speculate medieval pageant wagons would have appeared in contemporary cycle plays.

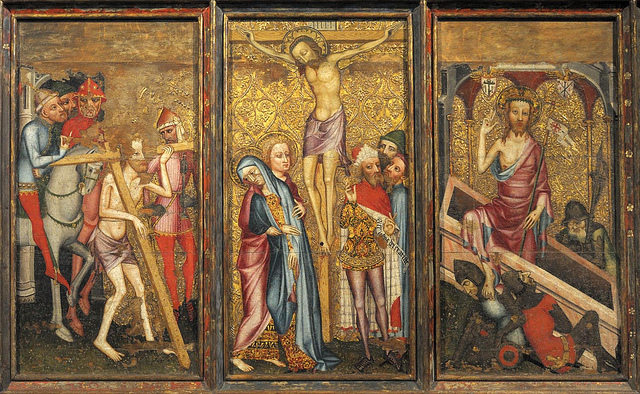

While we have few representations of medieval English stage design, examples from the continent such as Denys van Alsloot's The Triumph of Archduchess Isabella and the Valenciennes Passion suggest that both pageant wagons and stand-alone scaffolds had the potential to be elaborate, multi-story structures. Similar to the donor portraits depicted in stained glass windows and other religious and semi-religious artwork of the period, such structures evoked contemporary architectural and design preferences rather than those of their Biblical and religious source material. For example, Jesus' Tomb in East Anglian artwork is often represented by a stone tomb chest, which was a preferred burial method for the well-off in the period. This can be seen in roof boss NN10 and the Depenser Retable at Norwich Cathedral, and it is likely that Christ's entombment and resurrection in drama would have used the same sort of tomb chest.

The central three panels of the Depenser Retable at Norwich Cathedral. These three panels are the center of a sequence of five, and depict the carrying of the cross, crucifixion, and the resurrection of Christ. Note how Christ is stepping out of a tomb chest rather than out of a cave, as is more commonly depicted in modern representations.

Stage costuming reflected the social class and dramatic and narrative functions of the characters as they would have been understood by the audience, rather than conveying historical or scriptural accuracy. Characters who go on pilgrimage like the King and Queen of Marseilles in the Digby Mary Magdalene, for example, would likely be dressed in a way that signifies that status to the audience. Similarly, the "nice array" of Nought, New Guise, and Nowadays in Mankind marks them as followers of the latest fashion, and clothes play a symbolic role in stripping away Mankind's virtue once he has made common cause with the three.

Spectacle

Medieval dramatic works often took advantage of what we would consider "special effects" today. Perhaps the most famous example is the direction in the staging diagram of the Castle of Perseverance regarding Belial's entrance for the battle scene: he is to have pipes filled with burning gunpowder in his hands, his ears, and his arse. But just as ambitious is the staging of the bleeding Host in the Croxton Play of the Sacrament, the expulsion of the Seven Deadly Sins from Mary Magdalene in the Digby Mary Magdalene, the withering of Salome's hand in the N-Town Nativity, and the use of light in the N-Town Salutation and Conception. There, in a striking visual translation of Mary's impregnation by the Trinity, the Holy Ghost descends to Mary alongside three beams, three beams shine from the Son of the Godhead to the Holy Ghost, and three beams shine from the Heavenly Father to the Son.

Stage properties also contributed to the sense of spectacle. The ship in the Digby Mary Magdalene represents a movable stage that traveled throughout the place, carrying characters between locations. Likewise, a "cloud" is used to allow Christ, Mary Magdalene, and the Virgin Mary to rise into heaven (and in the case of Magdalene, to return to earth) in the Chester Ascension, Digby Mary Magdalene, and N-town Assumption. Both the Chester Last Judgement and Antichrist stage the resurrection of the dead from sepulchers, but the latter also stages the dead rising up from burial mounds in a performative analogue to visuals seen in manuscripts, stained glass, wall paintings on stone or wood, and roof bosses throughout England. Equally impressive would have been the use of reflectors, backed by candles, to represent fire and the visitation of the Holy Spirit; the ability of Hellmouth to open and close to admit or expel devils, Christ, and the souls of the damned; and the use of fire and smoke to represent the burning of the pagan temple in Marseilles in the Mary Magdalene.

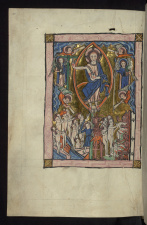

The Last Judgement from the Carrow Psalter (Walters W.34 f30v), with the dead rising on the left hand side. Image Courtesy the Digital Walters.

Music

Music played a significant role in the performance of medieval drama. REED shows that musicians were paid for performing before, after, and within plays; for entertainments associated with religious festivals and feasts; and for providing musical accompaniment to entertainments such as Morris dances. Medieval English drama is full of references to performed liturgical music. Angels are directed to sing hymns - for example the "Ave Maria" in the N-Town Salutation and Conception, "Veni Creator" in the N-Town Marriage of Mary and Joseph, and "Te Deum Laudamus" at the end of the Digby Mary Magdalene. Such references to the performance of liturgical music-often noted by title or more often by the first few words sung-suggests a deep familiarity by dramatic producers and performers with sacred music. Their use of these songs to serve the narrative of the plays also suggests a confidence that their audience would be familiar with and understand the significance of these songs as well.

Additionally, musical cues appear within the manuscript texts of medieval English plays. These may take the form of stage directions indicating that musicians "trump up," meaning that they use trumpets, drums, and other instruments; or they may involve more subtle cues such as the use of both horns and voice to repeat the First Shepherd's "Howe" in the Chester Shepherd's Play. Plays also feature a number of unnamed songs such as that of the Shipman and Boy in the Digby Mary Magdalene and the song of Noah and his Wife in the Chester Noah. Although no musical notation is given, such songs are clearly intended to be performed. Within the extant dramatic manuscripts, the lack of musical notation to accompany clear evidence of dramatic musical performance serves to obscure the larger role of music in the development of dramatic character and plot.

Further Reading

Albin, Andrew. "Aural Space, Sonorous Presence, and the Performance of Christian Community in the Chester Shepherds' Play." Early Theatre 16.2 (Dec 2013): 33-57.

Bush, Jerome. "The Resources of Locus and Platea Staging: The Digby Mary Magdalene". Studies in Philology 86.2 (1989): 139-165.

Butterworth, Philip. Staging Conventions in Medieval English Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Davidson, Clifford. Technology, Guilds, & Early English Drama. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 1997.

_____. "Space and Time in Medieval Drama: Meditations on Orientation in the Early Theater". In Word, Picture, and Spectacle (Early Drama, Art, and Music Monograph Series, 5). Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 1984. 39-93.

Meredith, Peter. "The Iconography of Hell in the English Cycles: a Practical Perspective". In The Iconography of Hell. Eds. Clifford Davidson and Thomas H. Seller. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, 1992: 158-186.

Twycross, Meg. "The Theatricality of Medieval English Plays". In The Cambridge Companion to Medieval English Theatre. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1994: 37-84.

Weimann, Robert. Shakespeare and the Popular Tradition in the Theater: Studies in the Social Dimension of Dramatic Form and Function. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1978.