Medieval Drama and Performance-Based Pedagogy: Difference between revisions

MariaHorne (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

MariaHorne (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

====== Lesson Plans 1 through 4 ====== | ====== Lesson Plans 1 through 4 ====== | ||

In the Biblical account that underwrites medieval drama, God gave man the power of naming, and thus united words and things. But in the world we inhabit today, words are frequently separated from actions, and we are shy or disempowered, and read privately or do not know how to connect our words with what we do. | In the Biblical account that underwrites medieval drama, God gave man the power of naming, and thus united words and things. But in the world we inhabit today, words are frequently separated from actions, and we are shy or disempowered, and read privately or do not know how to connect our words with what we do. | ||

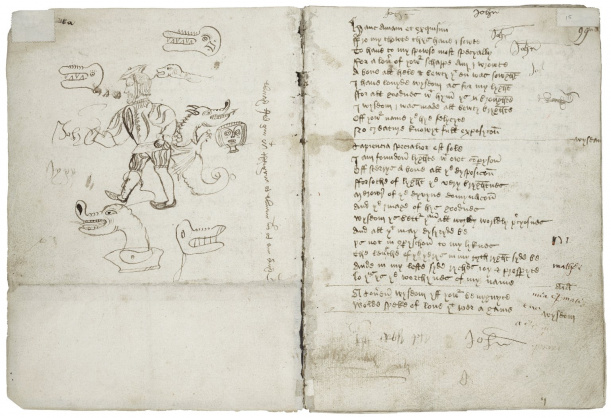

[[File:Monreale, Christ the Creator.JPG|left|thumb|''Christo Pantocratore''. Monreale Cathedral, Photo by Nicholas DiMichael.| | [[File:Monreale, Christ the Creator.JPG|left|thumb|''Christo Pantocratore''. Monreale Cathedral, Photo by Nicholas DiMichael.|231x231px]] | ||

In order to move toward a fully embodied understanding and performance of the speaking picture that is medieval drama it can be helpful initially to separate its forceful but often seemingly unfamiliar language from its physical embodiment as images and things, to detach these words and things at first from their plots so as to familiarize them through defamiliarization before reintegrating them as performance. Put simply, novice actors can speak, enjoy, and come to understand some words and phrases, or appreciate a concrete and symbolically-laden prop or a freeze-frame moment, as a preparation for integrating these words and things into a lively action. Try some of these exercises with your students, and see how they will begin to become comfortable with some of the key words and things informing medieval drama, and begin as well to bond together into a company of players. | In order to move toward a fully embodied understanding and performance of the speaking picture that is medieval drama it can be helpful initially to separate its forceful but often seemingly unfamiliar language from its physical embodiment as images and things, to detach these words and things at first from their plots so as to familiarize them through defamiliarization before reintegrating them as performance. Put simply, novice actors can speak, enjoy, and come to understand some words and phrases, or appreciate a concrete and symbolically-laden prop or a freeze-frame moment, as a preparation for integrating these words and things into a lively action. Try some of these exercises with your students, and see how they will begin to become comfortable with some of the key words and things informing medieval drama, and begin as well to bond together into a company of players. | ||

Revision as of 15:23, 22 March 2018

This article is under construction

This article - conceived and written by Barbara J. Bono, Maria S. Horne, and Michelle Markley Butler - is associated with the Folger Institute's 2016-2017 year-long colloquium on Teaching Medieval Drama and Performance, which welcomed advanced scholars whose research and pedagogical practice explore historical, literary, and theoretical dimensions of medieval drama from the perspective of performance.

Introduction

Medieval drama truly comes alive in performance.

This is, of course, a statement true of all works in the dramatic genre. However, it is especially true of medieval drama, which frequently addressed in embodied form large and ultimate questions about humanity's place in creation and the scheme of history, and did so in direct and explicit relation to its audiences, with extraordinary emotive and affective range from the obscene to the exalted.

Medieval drama is integrated into the curriculum for theatre majors at most universities in the United States. However, there, rather than being part of acting technique or performance-based courses, or of staged productions, the subject is most often studied only very briefly in lecture courses like Theatre History. Meanwhile, in departments of literature, medieval drama is sometimes included as a topic in a broader medieval or British literature class or as a minor prequel to the drama of Shakespeare and his contemporaries, but it is seldom given much time or attention, and its performative nature is largely neglected.

But we would argue that medieval drama is accessible, exciting, adaptable, and inspirational to interested communities of all ages and abilities - from lower grade levels to highly-trained practitioners - for drama itself is the ideal synesthetic and interdisciplinary vehicle for community formation and differential learning. There is also contemporaneity in medieval drama: humor, music, and fun, as well as metaphor, allegories, and subtexts which speak to who we are today. And while the task of accessing this excitement may seem daunting, in this article we have put together a set of resources - combining language, action, and spectacle - to get you started.

The first step in bridging the gap between performance and literary study is alerting students and teachers to the new wealth of readily-available textual and general scholarly resources for these plays, which reach far beyond the frequently anthologized Everyman or the de-contextualized bit of a biblical cycle play.

Ten Performance-Based Lesson Plans for Medieval Theatre

The second step is to make at least a beginning at "putting the plays up on their feet." To that end we have supplied a series of ten performance-based Lesson Plans which build up from the rich relationship of word and thing, to considering the symbolic shape of an action, to preliminary training toward full performance and modern adaptation. While these Lesson Plans are designed as a sequence to support extended work, they may also be sampled and adapted strategically for shorter teaching units. Suitable for all kinds of students from the novice to the budding professional, they follow the format of the famous Folger Shakespeare Set Free teaching manuals, namely "What's On for Today and Why?," "What to Do?," and How'd It Go?" They offer some suggestions for how to capture the vitality of medieval drama in short time and limited space, and build on some of the best continuing scholarship in the field. They imply, as well, an on-going engagement in the developing interdisciplinary field of Performance Studies, which combines interest in the performing arts and literary theory with the fields of anthropology and sociology.

Verba et Res/Words and Things: The Speaking Picture of Medieval Drama

Lesson Plans 1 through 4

In the Biblical account that underwrites medieval drama, God gave man the power of naming, and thus united words and things. But in the world we inhabit today, words are frequently separated from actions, and we are shy or disempowered, and read privately or do not know how to connect our words with what we do.

In order to move toward a fully embodied understanding and performance of the speaking picture that is medieval drama it can be helpful initially to separate its forceful but often seemingly unfamiliar language from its physical embodiment as images and things, to detach these words and things at first from their plots so as to familiarize them through defamiliarization before reintegrating them as performance. Put simply, novice actors can speak, enjoy, and come to understand some words and phrases, or appreciate a concrete and symbolically-laden prop or a freeze-frame moment, as a preparation for integrating these words and things into a lively action. Try some of these exercises with your students, and see how they will begin to become comfortable with some of the key words and things informing medieval drama, and begin as well to bond together into a company of players.

- Lesson Plan 1: Playing around with medieval language

- Lesson Plan 2: The twenty props you need to put on any medieval drama

- Lesson Plan 3: Typology, or medieval living history

- Lesson Plan 4: Typology, or medieval living history and tableau vivant

Setting the Medieval Stage

Lesson Plans 5 through 7

The spaces of medieval drama were various, labile, and indeed often mobile. The York Biblical cycle plays processed annually on pageant carts into and about the city to stop at York Minster and end on the market Pavement; small travelling companies acted other plays, performing in open spaces, inn yards, or great houses. Later, as plays retreated into manuscript, they might have been brought out for occasional declamation. Plays of such sharp moment and open engagement could, in theory, take place anywhere on this middle earth. As Peter Brook famously began his 1968 classic, The Empty Space, “I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage. A man walks across this empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and that is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged,” and modern revivals of medieval plays have utilized halls, cloisters, hillsides, city plazas and streetscapes, as well as more formal stages. These three Lesson Plans encourage you to find a suitable space for your play exercises, from a classroom with the desks pushed back to the more formal stage to the outdoor green space which might draw in community passers-by. Then we offer you a selection of monologues for actors and especially powerful scenes to help develop the craft of your ensemble.

- Lesson Plan 5: Stages for medieval drama

- Lesson Plan 6: Filling the space. Medieval monologues and the power of words

- Lesson Plan 7: Creating and inhabiting the space. Scenes from medieval drama

Performing Medieval Drama: Audiences, Communities, and Adaptations

Lesson Plans 8 through 10

Medieval drama engaged and hoped to transform its audiences with its biting and cathartic humor, its pointed social observation, its religiously inflected heights and depths, and its joy, and it forged community in its gatherings. These are goals to which we can aspire in our teaching, and we can do this with youngsters and oldsters as well as formal students and professionals, and in our street and cities as well as in our classrooms and regular theaters. Some of us are fortunate enough to be theatre professionals, and to do this as the core of our vocation. Others do it more occasionally, or aspire to do something like it in our communities. In these final three Lesson Plans we invite you to think hard about the audiences whom you hope to reach in your work, and we offer you the inspiring account of two younger academics from our group who have had the training, creativity, and institutional support to mount entire student productions, in one case for a large public university Honors College seminar filled with STEM students, and in another at a liberal arts college embedded in a large city. Finally, we encourage you to take the tradition of street performance of medieval drama and the example of some modern adaptations to think about its transformative potential for pressing modern needs such as increased civic engagement, social justice, and ecological awareness.

- Lesson Plan 8: Determining your audience for medieval drama

- Lesson Plan 9: Performance of medieval drama

- Lesson Plan 10: Adaptations of medieval drama

Medieval and early English drama, print and on-line editions

Print editions

The Broadview Anthology of Medieval Drama. Christina M. Fitzgerald and John T. Sebastian. Broadview, 2012.

Medieval Drama: An Anthology. Greg Walker. Wiley-Blackwell, 2000.

Three Late Medieval Morality Plays. G.A. Lester. New Mermaids, 2002.

York Mystery Plays: A Selection in Modern Spelling. Richard Beadle and Pamela King. Oxford University Press, 2009

Early English Drama: An Anthology. John C. Coldewey. Routledge, 1993.

Medieval Drama. David Bevington. Hackett, 1975.

The Arden Early English Drama series of texts from the late fifteenth to the late seventeenth centuries currently includes Everyman and Mankind. Douglas Bruster and Eric Rasmussen. Methuen Drama, 2009.

On-line editions

Online editions vary considerably in quality. Below are some that we have found to be well edited for both scholarly and pedagogical purposes.

Modernized

Unmodernized

- The TEAMS Middle English Text Series: http://d.lib.rochester.edu/teams

Striking Monologues from Medieval Plays, for Performers

While the casting suggestions given here are gender- and age-normative, directors and actors may want to think about mixing up these conventions for special effect and/or to suit their needs.

| Play Title | Role | Gender | Context/Action | Text of scene | Print Edition | Online Editions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Towneley Second Shepherds’ Play | Coll (First Shepherd) | Male | This speech opens the play. Coll complains about the conditions that poor men like himself have to endure and the ways they are abused by rich men. The speech is important in its sympathy for the plight of the medieval working class, and also thematically: after Coll speaks, it is easy to understand why salvation in the form of the baby Jesus is needed to come into the world. | Lines 1-54 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. Ed. Greg Walker. Blackwell, 2000. | Modern English |

| 2 | Towneley Second Shepherds’ Play | Gib (Second Shepherd) | Male | This is the second speech of the play. Gib complains about the difficulties of being married, and how much he regrets it, but it’s too late. This speech is important for its insight into medieval humor (for better or worse, the ‘take my wife, please’ vein of jokes has been mined for a long time); thematically, it establishes that salvation is needed in the world because humans, in particular the sexes, are at odds. | Lines 55-108 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. Ed. Greg Walker. Blackwell, 2000. | Modern English |

| 3 | The York Fall of the Angels | God | Eternal | This speech opens not only this individual pageant but the York cycle as a whole. It sets the scene for both pageant and play, laying out themes that will recur throughout: the nature of God, the nature of creation, the nature of faith, the nature of worship, the consequences of disobedience. | Lines 1-34 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. Ed. Greg Walker. Blackwell, 2000. | Modern English |

| 4 | The York Crucifixion | Jesus | Male | This is Jesus’ speech from the cross after the soldiers finally manage to get him stretched and nailed to it. | Lines 253-264 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. Ed. Greg Walker. Blackwell, 2000. | Modern English |

| 5 | The York Last Judgement | God | Eternal | This speech opens the final pageant of the cycle. It harkens back to the first pageant and reminds the audience of all that happened between then and now, explaining the need for an end to be made and judgement given. | Lines 1-64 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. Ed. Greg Walker. Blackwell, 2000. | Modern English |

| 6 | The York Last Judgement | Jesus | Male | In this speech, Jesus addresses the human characters but, of course, also the audience, explaining why the judgement is going down as it does. | Lines 231-300 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. Ed. Greg Walker. Blackwell, 2000. | Modern English |

| 7 | ChesterThe Fall of Lucifer | God | Eternal | This speech opens not only the pageant but the cycle as a whole, laying out its important themes. | Lines 1-51 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. Ed. Greg Walker. Blackwell, 2000. | Modern English |

| 8 | N-town Passion Play 1 | Satan | Super-natural | This speech opens the Passion Play in the N-town manuscript. It is an important example of the ‘boast’ type of speech, common in medieval and early modern drama, where a villain or tyrant tells the audience who he is and that he is up to no good. [Shakespeare’s Richard III’s opening speech is a grandchild of this genre]. | Lines 1-124 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. David Bevington. 1975. | Modern English |

| 9 | Digby Mary Magdalene | Mary Magdalene | Female | In this speech, Mary Magdalene preaches about the creation of the world to a heathen king, hoping to persuade him to leave his pagan ways. | Lines 1481-1526 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. Ed. Greg Walker. Blackwell, 2000. | Middle English |

Challenging Scenes from Medieval Plays, for Acting Classes

While in many instances characters are all male, and probably youngish to middle-age, when they are representative/allegorical characters, gender and age may not matter much when casting the roles.

| Play Title | Roles | Gender | Context/Action | Text of Scene | Print Edition | Online Editions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mankind | New Guise, Nowadays, Nought, Mankind | Male | In this scene, the vices New Guise, Nowadays, and Nought try to tempt Mankind into sin. They fail spectacularly. Instead of recruiting Mankind as a diabolic minion, the devils are beaten up by him. This scene is important for understanding medieval drama because it illustrates physical action as an indispensable component that must be carefully choreographed and rehearsed to avoid injuring any of the actors. It also shows the use of physical comedy in medieval drama. | Lines 345-401 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. Ed. Greg Walker. Blackwell, 2000. | Modern English |

| 2 | Mankind | Titivillus, Mankind | Male | In this scene, the devil Titivillus has been called in by the other devils or vices who have failed to tempt Mankind into sin. Titivillus is invisible and inaudible to Mankind; but the audience can see and hear him, and they know Mankind cannot. This last piece is crucial, because Titivillus repeatedly speaks to the audience as if they are on his side, telling them to keep quiet to further his goal of tempting Mankind into sin (when of course they really are quiet because of their role as audience). This scene is one of several in the play that uses the audience’s role as audience to incite them to do bad things, thereby demonstrating that the audience needs redemption as much as does the character Mankind. | Lines 526-607 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. Ed. Greg Walker. Blackwell, 2000. | Modern English |

| 3 | Fulgens and Lucres | A

B |

Male | This scene opens the play. In it, A and B interact with the audience and with each other, all the while claiming that they are not part of the play, but there will be a play and they’re anxious to see it. B explains to A what the play will be about.

The scene is important because it demonstrates the fluid, meta-theatrical relationship between audience and play in early English theatre. |

Lines 1 - 201 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. Ed. Greg Walker. Blackwell, 2000. | |

| 4 | Robin Hood and the Sheriff of Nottingham (scene 1) | Sheriff,

Knight, and Robin Hood |

Male | In this scene, the Knight offers to capture Robin Hood for the Sheriff, who agrees to pay the Knight if he is successful. The Knight finds Robin Hood and engages with him in a series of tests of strength and skill. At last they fight. Robin Hood wins, kills the Knight, and declares that he will dress himself in the Knight’s clothes and take his head to the Sheriff to claim the reward for ‘killing’ Robin Hood.

This scene is useful in the classroom for several reasons. It is one of a very few surviving pieces of secular medieval English drama. It also provides an opportunity to demonstrate the challenges presented by the extant texts. There are few stage directions in early drama; but as this scene makes clear, it is crucial to puzzle out the action. Most of this scene is, in fact, action. How long would the scene run? That’s entirely dependent upon how a performance decides to handle the action. The contests could be quick, or they could be elaborate. |

Modern English | ||

| 5 | Towneley Second Shepherds’ Play | Coll,

Gib, Daw, Mak, Gyll |

Male

Female |

In this scene, the shepherds (Coll, Gib, and Daw) come to Mak and Gyll’s house, looking for their stolen sheep. Mak has indeed stolen the sheep and has persuaded his wife Gyll to help him hide it by putting it in their cradle and pretending it is their newborn baby.

The scene importantly demonstrates how medieval drama employs humor for thematic goals. For example, Mak swears to the shepherds that if he stole the sheep, the ‘baby’ will be the first meal he eats that day. It’s a funny line, for the audience knows the ‘baby’ is actually a sheep that Mak has every intention of eating. But discussion of eating the sheep/baby also underscores the nativity theme of the play, which celebrates the birth of a baby, Jesus, who is also a “lamb” who will be eaten (in the form of communion) for the benefit of humans. The parodic profane nativity highlights the sacred nativity. |

Lines 476-628 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. Ed. Greg Walker. Blackwell, 2000. | Modern English |

| 6 | The Castle of Perseverance | Mercy,

Justice, Truth, Peace, God |

Eternal | Humanum Genus, the play’s Mankind figure, has behaved wickedly most of his life. But as he is dying, he realizes his wickedness. His very last word is “Mercy,” begging God to save him from hell. In this scene, Justice and Truth argue before God why Humanum Genus should be damned. Peace and Mercy give their reasons why he should be saved. The scene resembles a modern courtroom drama, with Truth and Justice as the prosecuting attorneys, Mercy and Peace acting for the defense, and God the Judge listening to all sides before giving his verdict.

All characters are female except God, who is male. All are eternal figures. |

Lines 3129-3544 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. David Bevington. 1975. | Modern English |

| 7 | Brome Abraham and Isaac | Abraham,

Isaac, the Angel |

Male | Abraham is old. Isaac is a child. The Angel is ageless.

Abraham has been ordered by God to sacrifice his only son, Isaac. Naturally, Abraham is reluctant to kill his child, but he also wants to be obedient to God. In this scene, we see Abraham’s struggle. We also see medieval drama’s typological understanding of the sacrifice of Isaac as foreshadowing the sacrifice of Jesus. |

Lines 290-332 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. David Bevington. 1975. | Modern (lightly) English |

| 8 | Johan Johan | Tib the Wife,

John the Husband, and Johan Johan the priest |

Female

Male |

Tib is female and young adult. John the Husband is male and adult, perhaps a bit older than Tib, but theirs is not necessarily a May/December marriage. Johan Johan is male and adult.

The priest has been carrying on with several women in the area, including Tib. Tib and the priest laugh at the husband’s thickheadness in not realizing their liaison.. But John the Husband begins to get suspicious. This scene is particularly rich in physical comedy, as the husband is chafing wax from a candle to mend a leaky pail, with obvious masturbatory overtones--i.e,, the priest is getting real sex, the husband has to make do on his own. |

Lines 439-607 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. David Bevington. 1975. | Text |

| 9 | Wisdom | Lucifer,

Mind, Will, Understanding |

Allegorical | Lucifer explains to the audience that he is going to tempt the good guys, does so, and then brags about it. | Lines 325-55 | Medieval Drama: An Anthology. Ed. Greg Walker. Blackwell, 2000. | Middle English |

Some Productions of Medieval Plays, Online

You can access an extensive YouTube playlist of medieval drama online. Additionally, here is a resource list for some titles:

Everyman

You can find digital versions of various productions online, including a 2012 Everyman production at the Portland Community College Performing Arts Center which utilized large-scale puppets and a 2016 Everyman production by the Laurier Historical Society at Wilfrid Laurier University. The play has been adapted as a commercial film twice in recent years in modernized (2002) and period (2007) productions.

Mankind

The 1999 Mankind staging by Duquesne University Medieval and Renaissance Players.

University students staged an improvisatory modernized production of Mankind as a final course project in 2016.

Biblical cycle plays and passion plays

The Blackhills Passion plays were performed in Spearfish, South Dakota from 1939 to 2008, and at their winter home in Lake Wales, Florida from 1953 to 1999.

The Mormon Hill Cumorah biblical pageant in Palmyra, New York has been performed since 1935: http://www.hillcumorah.org/

The 2013 Chester Noah play performed by the Liverpool University Players.

The Chester Mystery plays were performed in a 2008 modernized musical version.

The Oberammergau Passion Play has been performed continuously in that Bavarian village since 1634. The trailer for the 2020 production.

The Towneley Second Shepherds’ Play has long been a favorite Christmas holiday production, and was recently revived at the Folger Theater in 2016.

Yiimimangaliso: The Mysteries, a version of the Chester mysteries, was staged in South Africa and London in 2001 and has been revived since.

The York cycle plays, England: Videos from recent York mystery plays are available on-line at several sites. See, for example, York Mystery Plays 1973, York Mystery Plays 2010, and York Mystery Plays 2016.

The York cycle plays, Toronto: 2010 “Crucifixion”.

The Poculi Ludique Societas, or PLS in Toronto, has for over 50 years now sponsored productions of early plays, from the beginnings of medieval drama to as late as the middle of the seventeenth century.

Selected Bibliography

Albin, Andrew. “Sonorous Presence, and the Performance of Christian Community in the Chester Shepherds Play.” Early Theatre 16.2 (2013): 33-57.

Aronson-Lehavi, Sharon. Street Scenes: Late Medieval Acting and Performance. Palgrave MacmIllan, 2011.

Beckwith, Sarah. “The Present of Past Things: The York Corpus Christi Cycle as a Contemporary Theatre of Memory.” Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies 26.2 (1996): 35-79.

Beckwith, Sarah. Signifying God: Social Relations and Symbolic Act in the York Corpus Christi Plays. University of Chicago Press, 2001.

Bevington, David. From “Mankind” to Marlowe: Growth of Structure in the Popular Drama of Tudor England. Harvard University Press, 1962.

Butler, Judith. Excitable Speech: A Politics of the Performative. Routledge, 1997.

Carlson, Marvin. “Medieval Street Performers Speak.” TDR:The Drama Review, 57.4 (2013): 86-94.

Chaganti, Seeta. “The Platea: Pre- and Postmodern: A Landscape of Medieval Performance Studies.” Exemplaria 25.3 (2013): 252-64.

Clopper, Lawrence. Drama, Play, and Game: English Festive Culture in the Medieval and Early Modern Period. Chicago, 2001.

Coletti, Theresa. “The Chester Cycle in Sixteenth-Century Religious Culture," Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 37.3 (2007): 532-47.

Coletti, Theresa. Mary Magdalene and the Drama of Saints: Theater, Gender, and Religion in Late Medieval England. University of Pennsylvania, 2004.

Coletti, Theresa. “Medieval Biblical Drama in Post-Apartheid South Africa: The Chester Plays in Afterlife.” Transformations in Biblical Literary Traditions: Incarnation, Narrative, and Ethics. Eds. D.H. Williams and Philip Donnelly, Notre Dame University Press, 2014. 268-88.

Coletti, Theresa. “Medieval Drama: 1191-1952.” Exemplaria 28.3 (2016): 264-76.

Coletti, Theresa. “Reading REED: History and the Records of Early English Drama.” Literary Practice and Social Change in Britain, 1380-1530. Ed. Lee Patterson, University of California Press, 1990. 248-84.

Davidson, Clifford, ed. Gesture in Medieval Drama and Art. Medieval Institute, 2001.

Elliott, John R., Jr. Playing God: Medieval Mysteries on the Modern Stage. University of Toronto Press, 1989.

Emmerson, Richard. “Dramatic History: On the Diachronic and Synchronic in the Study of Early English Drama.” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 35:1 (2005): 39-66.

Emmerson, Richard K. “’Nowe Ys Common This Daye’: Enoch and Elias, Antichrist, and the Structure of the Chester Cycle.” Homo, Memento Finis: The Iconography of Just Judgment in Medieval Art and Drama. Ed. David Bevington, et. al. Medieval Institute, 1985. 221-57.

Enders, Jody. The Medieval Theater of Cruelty: Rhetoric, Memory, Violence. Cornell University Press, 2002.

Gardiner, Harold. Mysteries’ End: An Investigation of the Last Days of the Medieval Religious Stage. Yale University Press, 1946.

Hardison, O.B., Jr. Christian Rite and Christian Drama in the Middle Ages: Essays in the Origin and Early History of Modern Drama. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1965.

Holsinger, Bruce. “Analytical Survey 6: Medieval Literature and Cultures of Performance.” New Medieval Literatures 6 (2003): 271-311.

James, Mervyn. “Ritual, Drama, and Social Body in the Late Medieval Town.” Past & Present 98 (1983):3-29.

King, Pamela, ed. The Routledge Research Companion to Early Drama and Performance. Routledge, 2017.

King, Pamela. The York Mystery Cycle and the Worship of the City. D.S. Breer, 2006.

Kolve, V.A. The Play Called Corpus Christi. Stanford University Press, 1966.

Lerud, Theodore. Memory, Images, and the English Corpus Christi Drama. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.

Normington, Katie. Gender and Medieval Drama. D.S. Brewer, 2004.

Normington, Katie. Modern Mysteries: Contemporary Productions of Medieval English Dramas. D.S. Brewer, 2007.

Normington, Katie. Medieval English Drama: Performance and Spectatorship. Polity Press, 2009.

Parker, Andrew, and Eve Kosofsky Sedwick, eds. Performativity and Performance. Routledge,1995.

Ong, Walter. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word. Methuen, 1982.

Overlie, Mary. Standing in Space: The Six Viewpoints Theory and Practice. Fallon Press, 2016.

Rogerson, Margaret. Playing a Part in History: The York Mysteries, 1951-2006. University of Toronto Press, 2009.

Sergi, Matthew. Work-in-progress on Play Texts and Public Practice in the Chester Cycle, c.1421-1607.

Schreyer, Kurt. Shakespeare’s Medieval Craft: Memories of the Mysteries on the London Stage. Cornell University Press, 2014.

Soleo-Shanks, Jenna. “Resurrecting Callimachus: Pop Music Puppets, and the Necessity of Performance in Teaching Medieval Drama." Teaching Medieval and Early Modern Cross-Cultural Encounters. Eds. Karina F. Attar and Lynn Shutters, Palgrave Macmillan 2014. 199-213.

Sponsler, Claire. “The Culture of the Spectator.” Theater Journal 34 (1992): 15-29.

Sponsler, Claire. Ritual Imports: Performing Medieval Drama in America, Cornell University Press, 2005.

Stevens, Martin. Four Middle English Mystery Cycles. Princeton University Press, 1987.

Stevenson, Jill. Performance, Cognitive Theory, and Devotional Culture: Sensual Piety in Late Medieval York. Palgrave MacMillan, 2010.

Travis, Peter W. Dramatic Design in the Chester Cycle. University of Chicago Press, 1982.

Turner, Victor. From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play. PAJ Books, 1982

Westfall, Suzanne R. Patrons and Performance: Early Tudor Household Revels. Clarendon Press, 1990.

Page written by

Barbara J. Bono, University at Buffalo, SUNY

Maria S. Horne, University at Buffalo, SUNY

Michelle Markey Butler, University of Maryland