Symbols of Honor exhibition material

This article offers a comprehensive and descriptive list of each piece included in the Symbols of Honor: Heraldry and Family History in Shakespeare's England, one of the Exhibitions at the Folger.

The Medieval Heritage

Beginning in the fourteenth century, the creation of genealogies and coats of arms had become the domain of a group of professional "heralds at arms" who established a set of rules which were part of the "law of arms." At the same time, biblical genealogies began to be depicted in graphic form, with scribes starting to use systematic interconnected roundels to explain inter-generational relationships. The items shown, on loan from the Rare Book Department at the Free Library of Philadelphia, are early examples of this innovation.

Peter of Poitiers is thought to have created the earliest genealogical chart, or family tree, recording the line of descent from Adam and Eve to Christ. These diagrams consisted of names inside roundels, connected by lines to indicate descent from one generation to the next. This final membrane of a thirteenth-century copy of the Compendium also includes miniatures of Christ’s birth, crucifixion, and resurrection.

A Genealogical Roll

Edward IV, King of England from 1461 to 1483, seized the throne toward the end of "the Wars of the Roses," the dynastic struggle between the noble houses of Lancaster and York. The Lancastrians (Henry IV, V, and VI) had the red rose as their badge, while the Yorkists (Edward IV and Richard III) used the badge of a white rose.

This number=Lewis%20E%20201 elaborately decorated parchment roll was made to demonstrate King Edward IV’s royal ancestry all the way back to Adam, and includes depictions of the resurrected Christ, Old Testament patriarchs, Roman emperors, Anglo-Saxon kings, and an armored Edward IV astride a horse. His personal motto, Counfort et lyesse (Comfort and joy) appears in many places, indicating that the roll was made for Edward himself. It emphasizes his legitimacy as king and his hereditary rights to the crowns of England, France, and Castile.

Genealogical rolls like this adopted the same diagrammatic format as the biblical genealogies, but with names and texts in squares and rectangles rather than roundels. Fifty-four coats of arms identify key individuals in the genealogy.

Items included

- LOAN courtesy of the Rare Book Department, Free Library of Philadelphia. Edward IV. Manuscript roll on vellum, England, ca. 1460s. Free Library Call number: Lewis E 201 and number=Lewis%20E%20201 Digital Image and Digital Scriptorium page.

- LOAN courtesy of the Rare Book Department, Free Library of Philadelphia. Peter of Poitiers. Membrane from Compendium historiae in genealogia Christi. Manuscript, ca. 1280. Free Library Call number: Lewis E 249a and Digital Image and Digital Scriptorium page.

The Order of the Garter and The Garter King of Arms

The Order of the Garter, founded by Edward III in 1348–9, was the first chivalric order of Europe. From 1415, it had its own herald, Garter King of Arms. The motto of the Order, Honi soit qui mal y pense (Evil be to him who evil thinks) is inscribed on the Garter surrounding the royal arms and the arms of all knights of the Order.

Every knight of the Order of the Garter was given a copy of the Order's statutes when he was elected to it. This copy has revisions and additions down to January 1559, and was probably written for Henry Manners, Earl of Rutland, who was elected a knight in 1559 and whose arms appear on the second leaf.

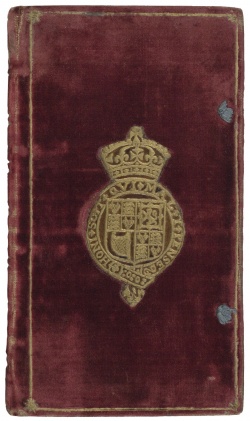

The royal arms encircled with the Garter appeared everywhere, including on bindings. King James I of England must have commissioned the binding of this copy of his Meditation upon the Lord's Prayer, since his own arms (as King of England, Scotland, and Ireland) are surmounted by a crown and inlaid in gilt on crimson velvet. He most likely intended this luxurious copy to be given away.

This collection of coats of arms of knights of the Garter was presented to James I in 1606 by William Segar, Garter King of Arms, who penned it himself. The arms, within a collar of the Order of the Garter, are intended to be those of Thomas FitzAlan, earl of Arundel, whose family history is recounted on the facing page. As a penciled note by a later owner remarks, Segar has unfortunately inverted the colors of this most celebrated coat of arms: by showing the lion as red and the field as gold, he has given the arms of the Charleton family, Lords Powys.

Items included

- Order of the Garter. The statutes and ordinances of the Order of the Garter. Manuscript, 1517–59. Call number: V.a.86; displayed fol. 3.

- James I, King of England. Meditatio in orationem Dominicam. London: Bonham Norton and John Bill, 1619. Call number: STC 14385; displayed cover and LUNA Digital Image and Binding image on LUNA.

- Sir William Segar, Garter King of Arms. Names and arms of the Knights of the Garter. Manuscript, 1606. Call number: V.b.157; displayed fol. 16 and LUNA Digital Image.

French Influences

English heralds were greatly influenced by the French tradition of heraldry. French was the language in which heraldic terms were expressed in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and the technical vocabulary of heraldry in England has continued to be partly in French ever since. Favored English noblemen were elected to the French King’s Order of St-Michel, just as the English Crown occasionally honored Continental monarchs by electing them to the Order of the Garter.

This collection of heraldic manuscripts, used by a series of English heralds, was perhaps compiled by William Harvey, Clarenceux King of Arms. It includes the statutes of the order of St-Michel, a French chivalric order which was modeled on that of the Garter.

In the 1530s, an English herald included in this reference guide a list of French marquesses, princes, cardinals, and bishops during the time of Henry VI of England (reigned 1422–61 and 1470–71), with sketches of many of their coats. The manuscript is full of densely-written lists and notes relating to both English and Continental kings and noblemen.

Claude Paradin’s massive work on the genealogies and coats of arms of the kings and queens of France provided inspiration for English heralds such as William Dugdale, who modeled his Baronage on it. This opening provides essential details about the reign and family of King Henry II of France. His arms are shown on the left. Those of his wife, Catherine de Médicis, are at right in lozenge (diamond) form, as is customary for women—her arms are France (three fleurs de lis, on the left) impaling Médicis (on the right).

Items included

- William Harvey, Clarenceux King of Arms. La table des chapitres du livre de l'ordre de St Michel. Manuscript, ca. 1610. Call number: V.a.154; displayed fol. 74.

- Miscellaneous collection of heraldic material relating to European and English families. Manuscript, ca. 1540. Call number: V.a.337; displayed fol. 12v–13r and LUNA Digital Image.

- Claude Paradin. Alliances genealogiques des rois et princes de Gaule. Geneva: Jean de Tournes, 1606. Call number: 211- 622f; displayed p. 118–19.

Tournaments and Armor

Heralds played an important role in the staging of tournaments—elaborate and extravagant occasions for displaying one's skill in the martial arts. Clarenceux King of Arms or another herald proclaimed the occasion, recorded coats of arms, and kept score. Sir Henry Lee, who was Elizabeth I's self-styled "Queen's Champion" in the 1580s, organized the Accession Day Tilts. These were tournaments held on each anniversary of the Queen's Accession Day, November 17. Elizabeth favored men who excelled at the tilts, and her courtiers spent an enormous amount of money to create customized armor, decorated with their arms, badges, or imprese for these tournaments.

The Almain Armourer's Album, on loan from the Library of Congress, Washington, DC, is a collection of designs for plate armors, now attributed to Jacobe Halder, the German (Almain) in charge of the royal armor workshops at Greenwich from 1576 until shortly before he died in 1608. Plate armor was worn in tournaments and on the parade ground. The armors were made for the Crown and leading courtiers, and were extremely costly. The plate displayed in the exhibition is of the subsidiary pieces that were made for Sir Christopher Hatton's full outfit. They include his horse's shaffron, and saddle steels for the horse's pommel and cantle, as well as two stirrups. Also shown is Hatton's armet with extra visor piece.

For more on arms and armor, visit Now Thrive the Armorers: Arms and Armor in Shakespeare.

Items included

- LOAN courtesy of Collections Access, Loan & Management Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Facsimile edition. An Almain Armourer's Album. Greenwich: English Royal Armory, 1557–87. London: W. Griggs, 1905. LOC Call number: NK6604 .A4 FT MEADE; displayed plate XXIV.

- LOAN courtesy of Private Collection. Half-shaffron armor belonging to the armor of Friedrich of Ulrich, Duke of Brunswick. English, Greenwich, 1610–13. Steel, etched, blued, and gilt, with polychromy.

Visitations

From 1530 to 1680, heraldic visitations were one of the primary means to record descents, marriages, and births, to confirm and grant arms, and to resolve uncertainties over arms. The formal nature of official visitations reflected the Crown's concern for maintaining records of the significant families in all parts of the kingdom. The two provincial Kings of Arms, Clarenceux and Norroy, or more typically, their deputies, carried out regular visitations of every county in their provinces.

Formal county-by-county visitations were instituted in 1530. Before that time, heralds collected regional genealogies in books such as this one, the earliest known copy of a regional collection of pedigrees for northern England, begun in the 1480s. The undulating lines, lack of dates, and many blank roundels, make it difficult to follow. In this opening, the Conyers pedigree from the previous opening comes to a conclusion, and the Aske pedigree begins. The limitations of the book format for lengthy family trees is obvious - the lines of descent would be much easier to read if they were set out on a long scroll.

Visitations were a lucrative business for the heralds, who collected a fee for every registration. This is a rare example of a surviving receipt from a visitation, signed by Thomas May, Chester Herald, and Gregory King, Rouge Dragon Pursuivant. It records the Mayor of Warwick's payment of thirty shillings for the registration of the arms of the Corporation of Warwick during the 1682 visitation of Warwickshire. Towns as well as individuals were required to show their right to arms, even if their usage had been continuous for three or four hundred years.

This 1619 visitation record of Warwickshire, made by a professional scribe, is in a more typical format, with rectilinear tabular pedigrees. The opening shows the genealogy of the Lucy family, of Charlecote, near Stratford-upon-Avon.

It was quite common to include one’s coat of arms on a seal ring or seal matrix, used to seal letters or official documents. This silver seal matrix was most likely produced as evidence by John Halsted of Pidley, Huntingdonshire, at the heraldic visitation of his county in 1684. The Folger Conservation Lab has made a new impression from the original matrix. Within the shield are an eagle displayed, that is, with its wings spread. Above the eagle is a chief chequy, a checkered band along the top of the shield. Since seals are a single color, the colors of the arms are not represented. This seal matrix of the Halsted family is on loan by the courtesy of Professor Sir John Baker.

Items included

- LOAN courtesy of Professor Sir John Baker. Pedigree of Wilson, examined and approved by William Segar, Garter King of Arms. Manuscript vellum roll, ca. 1620.

- William Jenings, Lancaster Herald of Arms. Pedigrees of some noble families. Manuscript, ca. 1525. Call number: V.b.163; displayed fol. 79.

- Receipt from Chester Herald and Rouge Dragon Pursuivant to the Mayor of Warwick. Manuscript, 1682. in a Collection of items relating to the Borough and Parish of Warwick. England 1551–1791. Call number: X.d.2 (37) and LUNA Digital Image.

- Henry Chitting, Chester Herald of Arms. Visitation of Warwickshire. Manuscript, 1619. Call number: V.b.52; displayed fol. 100.

- LOAN courtesy of Professor Sir John Baker. Seal matrix of the Halsted family. Silver, ca. 1620–80.

Grants of Arms

If an individual or family wanted to create, modify, or confirm a coat of arms, they would have to apply to a King of Arms for the right. If they met the requirements, the grantee would pay roughly twenty pounds (the equivalent of $15,000 or more in today's money) and commission a large parchment grant or letters patent, written or engrossed by a professional scribe, with the new coat of arms described or blazoned and professionally painted. The drawing up of letters patent for the granting of arms was a phenomenon that was common to all of Europe by the fifteenth century. These grants typically recounted a person's right to demonstrate with a coat of arms their wisdom, learning, knowledge, virtuous life, noble courage, integrity, and discretion.

Written in Latin in a careful italic hand, this confirmation of arms to Stephen Powle is signed at the bottom by Garter King of Arms, William Dethick. Along the top border are the badges of Queen Elizabeth: the white rose, the red and white double rose, as well as the Garter, and the royal arms. Powle's arms have a distinctive crest of a blue unicorn with a gold horn, mane, hooves, and tail. The arms themselves come from both paternal and maternal sides of the family. Powle's father's arms are three gold lions passant guardant on a blue background: that is, the lion strides to the viewer's left with its head facing the viewer. His mother's arms are described as three gold bends, or diagonal bands, on a blue background. The patent's artist, however, incorrectly depicted the bends in silver.

This example of a draft confirmation, confirms the arms of Thomas Pecke, alderman, justice of the peace, overseer, and former mayor of the city of Norwich. Like new grants, confirmations describe the grantee's status and his arms, and declare his right to display them on shields, swords, seals, rings, signets, buildings, utensils, tombs, monuments, and other surfaces.

This is a formal grant of arms and crest to Robert Horsseman, of Ripon (Yorkshire), by Robert Cooke, Clarenceux King of Arms, on May 26, 1590. The coat is described as "the field gold, three Gantlets Sable" with the crest "a burning Castell gold," that is, three black gauntlets (metal gloves used in combat) on a gold background, with a crest above consisting of a gold tower with flames coming out of it.

The language and format of grants of arms has changed very little over the centuries. There is no American herald today, but individual Americans, as well as American towns and other corporate bodies, can obtain honorary grants from the English College of Arms. As part of their bicentennial celebrations in 1976, Hampden-Sydney College, in Hampden-Sydney, Virginia, received a grant for an official coat of arms. The arms include two blue pheons, or spearheads, taken from the arms of the Sidney family of Penshurst, and two blue eagles against a silver background, from the Hampden arms.

Items included

- Robert Cooke, Clarenceux King of Arms. Grant of arms to Robert Horsseman of Ripon, Yorkshire. Manuscript, May 26, 1590. Call number: Z.c.40 (5) and LUNA Digital Image.

- William Camden, Clarenceux King of Arms. Confirmation of arms to Edward Lyster, doctor of physick of London. Manuscript, April 20, 1602. Call number: Z.c.22 (1) and LUNA Digital Image.

- LOAN courtesy of the Rare Books and Special Collection Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. King Philip II grant of arms. Grant or confirmation of arms to Alonso y Hernando de Mesa. Manuscript, Nov. 25, 1566. LOC Call number: Kislak MS 1014 Kislak Coll and LOC Digital Copy.

- William Dethick, Garter King of Arms. Confirmation of arms to Stephen Powle, citizen of London. Manuscript, March 15, 1588. Call number: Z.c.22 (41) and LUNA Digital Image.

- Gilbert Dethick, Garter King of Arms. Draft confirmation of arms to Thomas Pecke, Esq., late mayor of Norwich. Manuscript, ca. 1580s. Call number: X.d.280; displayed recto.

Shakespeare's Grant of Arms

William Shakespeare’s father, John Shakespeare, applied for a grant of arms in 1596. He then applied for a confirmation of arms in 1599, so that his wife’s arms could be impaled with his own. Although William Shakespeare’s name does not appear in the grants, the prosperous and successful playwright is assumed to have commissioned them on behalf of his aging father. Study of their handwriting indicates that the main scribe of each was William Dethick, Garter King of Arms.

Two draft grants of arms survive from the 1596 application, both dated October 20, 1596. One draft describes the arms as "gold, on a bend sable, a spear of the first, the point steeled argent"; that is, a gold background, with a black diagonal band set with a gold spear tipped with silver. The spear in the shield is a visual pun on the Shakespeare family name. The grant also describes the crest: "A falcon, his wings displayed, argent, standing on a wreath of his colors, supporting a spear gold, steeled argent." This miniature spear looks a bit like a metal pen, which was probably deliberate. The second draft’s neater script and its format, together with the fact that it incorporates some of the changes made to the first, suggest that it was intended as the model to be followed by the professional scribe who would write the patent of arms on parchment. Shakespeare’s motto Non sanz droict (Not without right) is included here, although it was not actually part of the grant and did not need to be recorded.

In a 1599 draft confirmation of arms, William Dethick, Garter King of Arms, and William Camden, Clarenceux King of Arms, confirms that John Shakespeare is entitled to bear the arms of Arden impaled with those of Shakespeare (i.e., that Shakespeare’s coat of arms could feature the Arden arms beside those of Shakespeare). Including the Arden arms would add luster to the Shakespeare family name, since John Shakespeare’s wife, Mary Arden, was an heraldic heiress. Two Arden coats of arms are drawn on this draft: the first is from another family with the Arden name; the second is the proper arms of Mary Arden’s family, drawn alongside after the mistake was realized. The Shakespeare family only ever used the 1596 arms, suggesting that this 1599 confirmation was never formally issued as a signed and sealed patent. These drafts are on loan to the exhibition by the courtesy of the Kings, Heralds, and Pursuivants of Arms.

Some controversy surrounds the Shakespeare grant of arms which you can learn more about in the Scholars' insights or on Folger's research blog, The Collation.

Items included

- LOAN courtesy of the Kings, Heralds, and Pursuivants of Arms. William Dethick, Garter King of Arms. Two draft grants of arms to John Shakespeare. Manuscript, October 20, 1596.

- LOAN courtesy of the Kings, Heralds, and Pursuivants of Arms. William Dethick, Garter King of Arms and William Camden, Clarenceux King of Arms. Draft confirmation of arms to John Shakespeare. Manuscript, 1599.

H.E.R.A.L.D.: Humble, Expert, Righteous, Aduysed, Learned, and Dutifull

William Smith actively campaigned for a position in the College of Arms for at least two years before being appointed Rouge Dragon Pursuivant on October 23, 1597. Over thirty of his beautiful manuscript creations survive, as well as a treatise in which he criticizes unfair promotions within the College of Arms and the unfair system of distributing fees among the heralds. In the treatise, he describes the College of Arms as a monster with three heads (the Kings of Arms), six bodies (the Heralds), and four legs (the Pursuivants).

Smith compiled this extensive Alphabet of arms, which contains nearly eleven thousand coats of arms, to make it easier “to fynde such as a man desyreth to know.” As the title page records, he began the work on October 20, 1594 and completed it on October 30, 1597, just one week after he was elected to the College of Arms as Rouge Dragon Pursuivant. The coats of arms in each of the four corners of the title page are those of the families of his mother, father, and German wife. His motto, Silentio et spe (Silence and hope), adorns the bottom center of the page. Queen Elizabeth’s royal coat of arms decorates the facing page.

On another opening, Smith depicts a herald and describes his duties and attributes. Heralds are messengers of nobility, overseers of justice, and revealers of truth. They must be Humble, Expert, Righteous, Aduysed (Advised), Learned, and Dutifull.

Items included

- William Smith, Rouge dragon Pursuivant. Alphabet or blazon of arms. Manuscript, 1597. Call number: V.b.217; displayed p. 1 and facsimile of title page and opposite.

The Business of Heraldry

Alphabets and Ordinaries

In order to satisfy the growing demand for new coats of arms, heralds needed to have at their fingertips all the thousands of coats that had ever been used. They relied on two main organizational approaches: Alphabets and Ordinaries. Alphabets consisted of an A-to-Z listing and illustration of the arms of every arms-bearing family and institution, organized by surname. Ordinaries consisted of arms arranged by ordinaries, the simple geometric shapes and figurative designs that serve as the basic structure of almost all coats. These books were updated as fresh grants of arms were made, and were passed down through generations of heralds. Alphabets and Ordinaries served as reference books for creating meaningful and aesthetically-pleasing arms, and for avoiding the duplication of previously-granted arms.

The heavily-used pages in this Ordinary, part of a two-volume set, are arranged by the type of geometric design or image that appears within the shield. It is open to a section of coats of arms that include a bend engrailed, a diagonal band with very wavy edges. Mostly written in the later sixteenth century, it was soon after acquired and added to by Ralph Brooke, York Herald.

This collection of several Alphabets gathered from various sources is thought to have belonged to Ralph Brooke, York Herald. It is open to coats of arms belonging to families whose surnames begin with the letter D, starting with "Davillers of Suffolke" and ending with "Demorby."

Not all armorial collections were organized alphabetically or by ordinary. Richard Mundy, an arms painter rather than a herald, made this collection of five hundred coats of arms and crests granted by Robert Cooke and Richard Lee, successive Clarenceux Kings of Arms. The range of popular Elizabethan designs is evident in this opening. On the left are scallop shells, cinquefoils (five-petaled flowers), and a pole-axe-wielding arm; on the right, a heart belonging to Edmund Scambler (d. 1594), Bishop of Norwich, and a smoking pistol belonging to Thomas Walle of Stonepit, Kent.

Funeral Processions

Heralds were paid meager salaries by the Crown, but they increased their incomes through a range of activities, including conducting heraldic funerals, making pedigrees, and verifying armorial bearings, and, for the Kings of Arms, granting arms. Funerals were particularly lucrative. Two or more heralds were often involved, and, in addition to their basic fee they received perks such as generous clothing and travel allowances.

In this reproduction of the funeral procession for Sir Christopher Hatton (ca. 1540-91), six heralds are visible, identifiable by their tabards. Hatton was a favorite courtier of Queen Elizabeth and a Knight of the Order of the Garter. Three of the heralds in the procession carry Hatton's achievements—the helm and crest of a golden hind (deer), the shield of arms and sword, and the heraldic surcoat, or literally, the coat of arms. The senior herald walks behind the coffin.

Hatton's arms, visible on the shield, appear within the garter. Although not shown in color on this manuscript roll, they consist of a blue background with a golden chevron between three golden garbs, or sheafs of wheat. His arms are quartered twelve times in the large banner that preceeds the heralds, and in the surcoat carried by the third herald.

Items included

- Ralph Brooke, York Herald, former owner. Ordinary of arms. Manuscript, ca. 1604. Call number: V.b.90; displayed fol. 317v–318r.

- Ralph Brooke, York Herald, former owner. Alphabet of arms. Manuscript, ca. 1600. Call number: V.b.145; displayed fol. 85v–86r.

- Richard Mundy, arms painter. Coats of arms granted by Robert Cooke, Richard Lee and others, ca. 1570-1600. Manuscript, ca. 1600. Call number: V.b.256; displayed fol. 46v–47r.

- FACSIMILE. Funeral procession of Sir Christopher Hatton. Manuscript roll on paper, ca. 1591. Call number: Z.e.3; displayed panels 4–9 and LUNA Digital Image.

Badges, Mottoes, and Imprese

Coats of arms were not the only form of heraldic identifier: badges, mottoes, and imprese could also depict the owner's identity. Simpler than coats of arms, badges usually consisted of a single image which appeared on anything from book bindings and seals to servants' clothing. Mottoes originated as war-cries shouted out to show support for a particular leader, but by the sixteenth century they had become hereditary to particular families. An impresa, from the Italian for badge or emblem, was a fashionable alternative to a coat of arms for an Elizabethan lady or gentleman. It was personal to its bearer, and was intended to be obscure in its meaning, understood only by friends.

The binding of this book, once owned by Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, is stamped with his badge: a bear and ragged staff with the motto Droit et loyal (Right and loyal). The badge was the ancient device of the Earls of Warwick, from whom Dudley claimed descent, and was first used by Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, in the fourteenth century.

Mottoes, which were often ambiguous in their meaning and could be translated in a variety of ways, posed as many questions of interpretation to contemporaries as they do today. In this collection of mottoes, translations have been attempted for most of the mottoes, and the names of families using them are also supplied. In this image, we see that Mihi Christi Trophaeum translates to "The badge of Christ for mee" or "Christ is my badge" and is used by "Mr. Walter Toock Awdyter." Tooke was auditor general of the Court of Wards and Liveries.

Camden's book of miscellaneous essays, his Remaines, devoted more pages to imprese than to traditional heraldry. He describes the two components of an impresa as the picture-body and the mottosoul. He was fascinated by names and phrases, and also included chapters on surnames, nicknames, anagrams, and rebuses, or "name-devises," such as a ram in the sea, from the seal of the abbot of Ramsey.

Dedicated to England's nobility and gentry, Thomas Blount's translation of a French work by Henri Estienne serves as a tantalizing source book for creating a personal device, or impresa. The author emphasizes that the device should capture all the rules of moral and civil life in a short motto and symbolic figure, and should be obscure enough so that it requires decoding by people who view it.

Items included

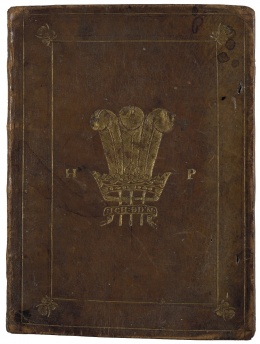

- Sir Charles Cornwallis. The life and death of our late most incomparable and heroique Prince, Henry Prince of Wales. Manuscript, ca. 1626. Call number: V.a.486; displayed front cover.

- Heinrich Bullinger. Bullae papisticae ante bienniumcontra sereniss. London: John Day, 1571. Call number: STC 4043 copy 1; displayed cover and LUNA Digital Image and Binding image on LUNA.

- Book of mottoes. Manuscript, ca. 1600. Call number: V.b.202; displayed fol. 7v–8r and LUNA Digital Copy.

- William Camden, Clarenceux King of Arms. Remaines, concerning Britaine:but especially England, and theinhabitants thereof. London: John Legatt, 1614. Call number: STC 4522 copy 8; displayed p. 211 and LUNA Digital Image.

- Henry Estienne. The art of making devises. Translated by Thomas Blount. London: W.E. and J.G, 1646. Call number: 154- 264q; displayed frontis.

Disputes within the College of Arms

Ralph Brooke vs. William Dethick

The College of Arms was plagued by rivalries and quarrelling in the 1590s. William Dethick, Garter King of Arms, was notorious for his arrogant and overbearing manner. He quarrelled with several of his colleagues, including Ralph Brooke, York Herald, in whom he met his match. Brooke accused Dethick of abusing his office in multiple ways: by granting arms to people who were of too lowly a status, who were not the Queen's subjects, or who were already dead, and by granting arms that were too similar to arms that already existed. The exclusivity and honor associated with the right to bear arms was at stake. Dethick was forced to resign in 1606 after numerous allegations of outrageous and unethical behavior.

Learn more about a debated coat of arms for a fishmonger from co-curator, Heather Wolfe, in this video.

Items included

- Ralph Brooke, York Herald. Detections and abusesse of William Derike of some called Garter Kinge of Armes. Manuscript, ca. 1595 Call number: X.d.313; displayed front and LUNA Digital Copy.

- Ralph Brooke, York Herald, compiler. Coats of arms granted by William Dethick as York Herald and Garter King of Arms, 1570–95. Manuscript, compiled ca. 1595 – ca. 1600, and facsimile of detail. Call number: V.a.156; displayed fol. 11v–12r and LUNA Digital Copy.

- Ralph Brooke, York Herald, compiler. Alphabet of Arms. Manuscript, ca. 1620. Call number: V.b.144; displayed p. 153–154 (image).

Ralph Brooke vs. William Camden

While Ralph Brooke, York Herald, waged one battle with William Dethick about the improper granting of arms, he waged another with his new colleague William Camden, Clarenceux King of Arms. Camden was the venerable author of Britannia, an extremely influential and innovative account of the local history and topography of the British Isles. Ralph Brooke responded to Britannia with A discoverie of divers errors, exposing Camden's genealogical inaccuracies in a mean-spirited and sarcastic fashion, and accusing him of ignorance in heraldic matters. The attack was largely prompted by Brooke's resentment that he had been overlooked for promotion, while Camden, who had no prior experience as a herald, was appointed Clarenceux, the senior provincial King of Arms.

Items included

- William Camden. Britannia. London: Eliot's Court Press, 1594. Call number: STC 4506 copy 2; displayed title page.

- Ralph Brooke, York Herald. A discoverie of divers errors published in print in the much commended Britannia, 1594. Very preiudiciall to the discentes and successions of the auncient nobilitie of this realme. London: J. Windet, 1599. Call number: STC 3834.2 copy 1; displayed title page.

- Ralph Brooke, York Herald. A second discoverie of certaine errovrs published in the much commended Britannia 1594 in a Collection of antiquarian papers. Manuscript, ca. 1600. Call number: V.b.218; displayed fol. 321r.

- FACSIMILE reproduced by kind permission of The Worshipful Company of Painter-Stainers, City of London. Unknown member of the Painter-Stainers' Company. Portrait of William Camden, Clarenceux King of Arms to Elizabeth I from 1597–1623. (Painted as either a retrospective or a copy.) Oil on canvas, 1637.

Ralph Brooke vs. Augustine Vincent

Ralph Brooke published his first attack on William Camden in 1599, and further antagonized Camden with A catalogue and succession, published twenty years later. Camden was by this time an elderly man, but he was capably defended by another herald, Augustine Vincent, Rouge Croix Pursuivant. Vincent responded with A discouerie of errours in the first edition of the catalogue of nobility. Vincent essentially reprinted Brooke's Catalog and added his corrections as separate paragraphs after each section. The debate turned into a learned discussion of the history of the English nobility, well worth the while for the publisher of both men's books, William Jaggard.

Items included

- Ralph Brooke, York Herald. A catalogue and succession . . . discoueringe, and reforming many errors committed, by men of other profession. London: William Jaggard, 1619. Call number: STC 3832.2 copy 3; displayed sig. 3v–4r.

- Ralph Brooke, York Herald. A catalogue and succession . . . by him inlarged, with amendment of divers faults, commited by the printer, in the time of the authors sicknesse. London: William Stansby, 1622. Call number: STC 3833 copy 5; displayed p. 1 with facsimile detail of title page and LUNA Digital Image.

- Augustine Vincent, Rouge croix Pursuivant. A discouerie of errours in the first edition of the catalogue of nobility. London: William Jaggard, 1622. Call number: STC 24756 copy 2; displayed p. 431 with facsimile detail from opening and Blog post, The Collation and LUNA Digital Image.

Heraldry for the Elite

Noblemen under Queen Elizabeth and King James went to great expense to commission elaborately illustrated pedigrees and family records. These documents established the proper ancientness of their English descents and displayed their coats of arms in glorious fashion. Unethical heralds would occasionally create fictional ancestors to provide additional honor and respectability, but this was not the norm.

William Bowyer presented an exquisitely written and illustrated manuscript to Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, in November 1567. Although not a herald himself, Bowyer's records-based scholarship helped raise the standards of pedigree making to new levels of accuracy and detail. The calligraphic passages are in the hand of Jean de Beauchesne, co-author of the first writing manual to be published in England. The volume consists of copies of grants and deeds concerning Robert Dudley's estates, interspersed with eulogies in verse of previous earls of Leicester and the kings who granted the various charters. Shown here is Leicester's achievement of arms, with sixteen quarterings. The crest at the top—the bear and ragged staff—was also used by Leicester as his badge. This item is on loan courtesy of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

The Genelogies of the Erles of Lecester and Chester, created in 1573, shows the descent of the two earls from ancestors dating back to the time of William the Conqueror. Robert Dudley was particularly conscious of his family's claims to a long noble lineage. The original ancestors are depicted with branches emerging from their bodies: they are the roots of the tree that grows through each page of the book, passing through heraldic shields and roundels with the names of principal family members. The tree motif is not merely decorative. The Leicester branch has oak leaves, and the Chester branch has elm leaves. Folio page 2r, illustrated with two knights, explains that roundels with two overlapping leaves signify direct descendants, while roundels with one overlapping leaf are the "colaterall children."

Items included

- LOAN courtesy of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. William Bowyer, Keeper of the Records in the Tower of London. Heroica Eulogia Guilielmi Bowyeri Regiae maiestatis archivorum infra Turrem Londinensem Custodis. Ad Illustrissimum Robertum Comitem Leigrescestrensem. Manuscript, England, November 1567. Huntington Call number: mssHM 160 and Digital Scriptorium Catalog description and Digital Copy.

- LOAN courtesy of the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania Libraries The Genelogies of the Erles of Lecester and Chester. Manuscript, ca. 1572–1573. UPenn Call number: Ms. Codex 1070 and UPenn Digital Facsimile.

Heraldry for All

Heralds, herald-painters, and professional scribes competed to produce manuscripts and printed books suitable for sale to the general public. The most popular type of heraldic manuscripts were "Baronages," short biographies and illustrations of the arms of the nobility from the time of William the Conqueror to the present. Even wider audiences were reached with printed guides to heraldry. These books were aimed at a readership that wanted to interpret the armorial landscape around them: the coats of arms, badges, mottoes, and other devices on buildings, banners, clothing, bookbindings, seals, paintings, utensils, and suits of armor.

Manuscript catalogs of the English nobility by such heralds as Robert Cooke found a very ready market. This Baronage, one of eight versions at the Folger, has hand-colored shields, making it more expensive than versions done in black ink alone. The full achievement of arms at left is that of Henry VIII, underneath his royal badges of the red rose of the house of Lancaster, the fleur-de-lis of France and of the house of Plantagenet, and the portcullis, a latticed grille that fortifies a castle, of the Beaufort family.

William Grafton, the owner of this copy of John Ferne's heraldic manual, used it like one might use a family bible. Beneath a note of the birth of his first son, William, on 16 November 1587, he included a painting of his coat of arms. This would be described in heraldic terms as per saltire sable and ermine, a lion rampant or, armed and langued gules: in the top and bottom triangles, a gold lion rearing up on its hind legs, with a red tongue and claws, against a background of black; in the left and right triangles, black spots on white, representing the stoat's winter coat of fur.

Gerard Legh's heraldic manual was a popular introduction to the mysteries of heraldry. He provided simple step-by-step instructions, in the form of a dialogue, for decoding and interpreting all facets of coats of arms. In doing so, he made them accessible to a curious public, hungry for details on how to decode the heraldic environment in which they lived. The arms that he illustrated are all imaginary, perhaps because he did not wish to give offence to the heralds by seeming to enter their jealously-guarded territory.

This is part of the original rough draft for John Guillim's popular and monumental Display of Heraldrie, published in 1611. It contains many more illustrations of arms and charges than are in the printed version, from which they were eliminated because of what Guillim describes on the last page as "the huge charge of cutting;" that is, the expense of making woodcuts. On the left are examples of "Fishes skynned," or soft fish, which could be incorporated into one's arms: the luce, eel, conger, plaice, sole, ray, tench, and trout. On the right are examples of "crusted," or hard fish: the small and great sea crab, cuttle fish, and lobster.

Items included

- Robert Cooke, Clarenceux King of Arms. An English baronage. Manuscript, 1572. Call number: V.b.76; displayed p. 128–29.

- Sir John Ferne. The Blazon of Gentrie. London: John Windet for Andrew Maunsell, 1586. Call number: STC 10825 copy 2; displayed A1v–A2r.

- Gerard Legh. The Accedence of Armorie. London: Richard Tottell, 1591. Call number: STC 15391 copy 3; displayed fol. 60v–61r.

- Edmund Bolton. The elements of armories. London: George Eld, 1610. Call number: STC 3320 copy 1 Bd.w. STC 3394 copy 2; displayed p. 198 and LUNA Digital Image.

- John Guillim, Portsmouth Pursuivant Extraordinary, later Rouge Croix Pursuivant. A display of heraldry. Manuscript, ca. 1610. Call number: V.b.171; displayed fol. 79v–80r.

- FACSIMILE. John Guillim. A Display of Heraldrie. London: William Hall for Raphe Mab, 1611. Call number: STC 12501 copy 1; displayed title page and LUNA Digital Image.

Women's Heraldry

The rules for women's heraldry were complicated by brothers, marriage, widowhood, and remarriages. Like men, women could inherit or be granted a coat of arms. Unlike men, women's arms never had a helm or crest on top of the shield, since women did not fight on the battlefield. A woman's coat of arms was generally in the shaped of a lozenge, or diamond, when she was unmarried or widowed, but was joined in a shield with her husband's arms upon marriage.

Anne Clifford's personal interest in inheritance issues is apparent in the way she read her copy of John Selden's book on inheritance, Titles of Honor. She underlined relevant passages and dog-eared important pages, paying particular attention to sections that might inform her in her battle to obtain her father's vast estates. In the chapter on women's titles, shown here, the headings about female inheritance are highlighted in pencil. She recorded on the title page that she read the book in February 1638.

In this pedigree from The Blazon of gentrie . . . for the instruction of all Gentlemen bearers of Armes, John Ferne addresses the issue of female heirs. The last row in the pedigree describes the three daughters—Margaret, Alice, and Ellen—as co-heirs, since they had no brother. If an arms-bearing man had only daughters, then they would each bear both of their parents' quartered arms, which would then be conjoined with the arms of their husband if they married. Their children would also be entitled to those arms.

Gerard Legh's rules for heraldry provided answers to frequently asked questions about how coats of arms were created and inherited. In the image bottom right, he addresses a series of hypothetical questions concerning women's arms: Can a woman bear her father's arms without difference? How should a woman bear arms if she is a widow? What if her mother dies and her father remarries and has a son? What if a woman with a coat of arms marries someone without a coat and they then have a son? His answers form a still-valuable heraldic grammar-book.

Items included

- Lady Anne Clifford, former owner. John Selden. Titles of Honor. London: William Stansby for Richard Whitakers, 1631. Call number: Folio STC 22178 copy 3 and LUNA Digital Image.

- Sir John Ferne. The Blazon of Gentrie. London: John Windet for Toby Cooke, 1586. Call number: STC 10824 copy 1; displayed Part 2, p. 80–81.

- Gerard Legh. The Accedence of Armorie. London: Richard Tottell, 1591. Call number: STC 15391 copy 2; displayed fol. 97v–98r.

The First Amateur Genealogists

Popular genealogy was born in the seventeenth century. While only a King of Arms could grant a coat of arms, anyone with the ability to read medieval documents could conduct genealogical research and compile a pedigree. Copying the pedigrees of royal families and noblemen also became an increasingly popular pursuit. As Sir Edward Dering (d. 1644) wrote in his notes for a history of his own family, "What is history but the pedigree of the world?"

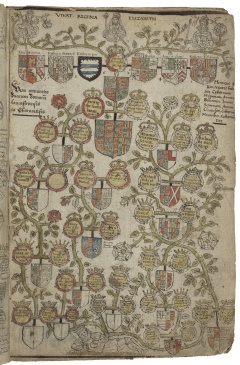

This pedigree of Queen Elizabeth is part of a collection of pedigrees and coats of arms that were copied out of a book in the College of Arms. It shows Elizabeth at the top of a leafy tree emerging from the belly of Edward III, who was the root of her family "tree." The largest coat of arms depicts the coming together of the House of Lancaster and the House of York in the marriage of Henry VII to Elizabeth, the daughter of Edward IV. The unknown compiler of this personal manuscript shows a clear interest in understanding the pedigrees of royal and noble Elizabethan families.

Edward Dering was the first person to write a records-based genealogical history of his own family. In the displayed opening, Dering proudly traces his family in Kent back to Saxon origins, before the invasion of William the Conqueror in 1066. He notes that the Domesday Book mentions one "Derinc," son of "Sired," whom he takes to be his ancestor. Dering obtained a warrant to search public records in the Tower of London, but when he could not locate genuine evidence, he filled the gaps in his family history with imaginative reconstructions, a practice also engaged in by a few professional heralds.

Items included

- A Collection of Armes in Blazon. Manuscript, ca. 1585–90. Call number: V.b.375; displayed p. 53.

- Sir Edward Dering. History of the Dering family from the time of the Conquest. Manuscript, ca. 1635. Call number: Z.e.27; displayed p. 4–5.

- LOAN courtesy of Hampden-Sydney College. John Brooke-Little, Richmond Herald. Grant of arms to Hampden-Sydney College, Virginia. Manuscript, July 4, 1976.