Symbols of Honor: Heraldry and Family History in Shakespeare's England

Symbols of Honor: Heraldry and Family History in Shakespeare's England, one of the Exhibitions at the Folger, was on display in the Folger Great Hall from July 1 to October 26, 2014.

The summer exhibition highlights a vital, richly visual aspect of Shakespeare's world: the coats of arms sought after by rising families (including the Shakespeares)—and the royal officials, called heralds, who granted them. Expert in family history, the heralds laid the groundwork for modern genealogy; they also feuded publicly and often.

Symbols of Honor showcases a treasure trove of the heralds' own papers from the Folger collection. It also includes some extraordinary loan items. Among them: a colorful pedigree of Edward IV, probably created for the king himself, and the original drafts of the Shakespeare grant of arms, which have left England for the first time for this display.

Curation

Symbols of Honor: Heraldry and Family History in Shakespeare's England was curated by Nigel Ramsay and Heather Wolfe.

Dr. Nigel Ramsay, co-curator of Symbols of Honor, has been a research fellow in the History Dept of University College London since 1997. He is a historian of medieval and Tudor England, and previously held posts at Canterbury Cathedral and in the Department of Manuscripts of the British Library. His study of the Tudor herald Robert Glover (d. 1588) will be published by the Harleian Society in 2014.

Dr. Heather Wolfe, co-curator of Symbols of Honor, is curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library. She has curated numerous Folger exhibitions and has written widely on early modern manuscripts and the intersections between print and manuscript. Recent publications include The Trevelyon Miscellany of 1608 (2007), The Literary Career and Legacy of Elizabeth Cary (2007) and Letterwriting in Renaissance England (2004), co-written with Alan Stewart.

Curators' insights

"Heraldry was a flourishing, live world" in Shakespeare's time, says Nigel Ramsay, co-curator of Symbols of Honor. "It mattered enormously to the Elizabethans and Jacobeans. For them, it meant status and honor. The right to a coat of arms might be litigated; some would even fight a duel." Increasingly, too, Elizabethan heraldry was for "up and coming merchants and gentry, people lower down the social scale" than in the past, further fueling its popularity.

To tell the story of that thriving, yet unfamiliar, aspect of Shakespeare's age, Ramsay and co-curator Heather Wolfe, the Folger curator of manuscripts, drew heavily on the Folger's holding of more than a hundred heraldic manuscripts, which Wolfe calls an "untapped treasure." Ramsay, who has been exploring the Folger heraldic collection for years on annual visits, says he has found "discoveries all over"—including the oldest copy in the world of the first English book of genealogies, Pedigrees of some Noble Families, from no later than 1525.

Although the manuscripts include beautiful display documents, Wolfe says that most of the Folger materials are "working papers that show the heralds as human beings. I'm excited about any manuscript that gives you a sense of the personalities," she says. "There was a lot of controversy about grants of arms, and you get a sense of how the heralds were arguing among themselves. It's very exciting to hold the manuscripts and to see what caused such consternation."

Some of the heralds were "extraordinarily tough, vicious fighters," says Ramsay of these disputes. But he also points to "one of the good guys," the herald William Smith, a scholar and gifted cartographer. An insightful observer, "Smith was able to produce this wonderfully revealing pamphlet about all that was wrong with heraldry as practiced in his day." Its image of a herald, he adds, may be a Smith self-portrait. The Folger has both of the two known copies of Smith's work.

Many of the heraldic papers are also "colorful, delightful, and playful," says Wolfe—a practical necessity since the heralds were required to make each coat of arms unique. A good example of "the creativity that went into it," she says, is an image-packed manuscript by John Guillim from about 1610, a source book of possibilities that is opened here to pages of fish, helpfully divided into soft fish and "crusted" ones (shellfish).

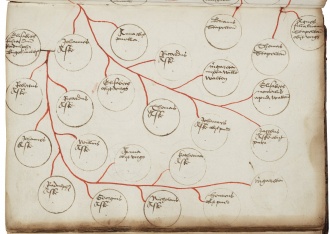

As the heralds dug into family records, often seeking earlier coats of arms that could legitimately be claimed, they laid the groundwork for modern genealogy, including basic tools like the family tree or pedigree. "It became easier to see the evolution of the modern family tree through these manuscripts," says Wolfe. "By the seventeenth century, they look exactly like they do now." At the same time, she adds, amateur genealogy took root, as individuals eagerly researched their own families' histories.

A number of extraordinary loan items add to the exhibition's story. Ramsay calls the pedigree scroll of Edward IV, from the Free Library of Philadelphia,"one of the most splendid pedigree rolls there is." Dated to the 1460s, it has "a late medieval form of beauty: crude, vigorous, and bright," he says. "And it belonged to a king. It's very rare to be able to say that."

The exhibition also includes an unprecedented American display of three draft manuscripts from the College of Arms, the primary organization of English heralds that remains active today. Two of the three are drafts of the original grant of arms to William Shakespeare's father John in 1596, which William inherited in 1601. The third proposes adding the Arden family arms of Shakespeare's mother, although the Shakespeares never used this revised version. Celebrating Shakespeare's personal links to heraldry in his 450th birthday year, all three have traveled from England for the first time for this display.

Contents of the exhibition

Contrary to popular belief, English Renaissance heralds did not play trumpets. Think of them as the earliest professional brand consultants, genealogists, and trademark protectors. They had the singular power to bestow enduring and easily recognizable symbols of status and honor upon individuals and institutions who had the proper lineage, reputation, and wealth.

These symbols formed a "coat of arms" that could be displayed on buildings, clothing, armor, monuments, rings, utensils, cups, plates—virtually anywhere the individual wanted to assert his or her status. Heralds created coats of arms that reflected the values, life story, and sometimes the last name, of the commissioning individual—such as Shakespeare’s “spear”on his arms. Heralds guaranteed that an individual’s arms were unique and regulated how they could be used by other family members.

The heralds suffered from a poor reputation because of the unstructured nature of the College and the quarrelsome ways of some of its members. Without these heralds, however, we would not have the modern family tree format, or access to rich caches of biographical material relating to families of English descent—information that plays such an important role in genealogical research today.

The Folger has a unique collection of the working papers of the most influential heralds from Shakespeare’ time. These manuscripts reveal the astonishing growth and importance of heraldry in the period, and the ways in which early modern heralds shaped modern genealogy.

Symbols of Honor exhibition material

This article offers a comprehensive and descriptive list of each piece included in the exhibition.

Image Gallery

To view images of exhibition highlights, visit this Flickr photo album.

Scholars' insights on Symbols of Honor

The controversy over Shakespeare's grant of arms

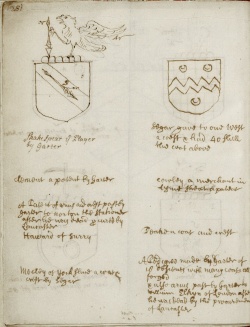

In 1602, twenty-three recently-granted coats of arms, including arms originally granted to Shakespeare’s father, were disputed by York Herald, Ralph Brooke. John Shakespeare died in 1601, and William Shakespeare inherited the arms at his father’s death. Brooke charged that Shakespeare’s arms were too similar to existing coats of arms, and that the family was unworthy.

Heralds William Camden and William Dethick defended the grant by clearly differentiating the arms from those of other individuals and pointing out that John Shakespeare was a justice of the peace of Stratford upon Avon who married the daughter and heir of the Arden estate. And beyond that, he "was of good substance and habelitie [ability]."

When Brooke challenged the group of arms granted by William Dethick, Garter King of Arms, he identified Shakespeare's arms as belonging to "Shakespear the Player by Garter." To describe Shakespeare as a Player rather than playwright was derogatory.

In this image, the arms are drawn in trick; that is, the colors are indicated by the letters o (Or, or gold), s (Sable, or black), and Ar (Argent, or silver). The manuscript in which these arms appear is a ca. 1700 copy, copiously annotated by the herald Peter Le Neve (d. 1729), Norroy King of Arms. It was copied directly from Ralph Brooke's original, which no longer survives.

Shakespeare's arms appear in a few later collections of coats of arms, such as this example from 1677, where they are described at the bottom of the left-hand page as "Shakespear, the great Poet and Commedian, bare on a Bend : a Spear ." The three blanks, where one would expect to see gold, sable, and gold (with a silver tip), indicate that the compiler knew only an uncolored version of the arms, such as that on a wax seal impression. The compiler was also unsure whether the crest featured a dove or an eagle, when in fact it is a falcon: "And for his Crest, Vpon a Torce of his Colours, a Doue Volant or Eagle." "Commedian" in this context means a writer of comedies, or non-tragic plays.

For more on the feuding heralds, watch this video.

Co-curator, Nigel Ramsay, also brings more detail to this debate on Folger's research blog, The Collation, in his post titled, William Dethick and the Shakespeare Grants of Arms.

Symbols of Honor children's exhibition

Supplemental materials

How to Decipher a Coat of Arms

A full achievement of arms consists of a crest, helm, supporter, mantling, shield, and motto. To learn more about the elements that make up a coat of arms, read this article.

Video

Heather Wolfe, co-curator of the exhibition and curator of manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library, shares a pedigree of Queen Elizabeth copied out of a book in the College of Arms.

Heather Wolfe, co-curator of the exhibition, shares a controversial coat of arms that reveals the rivalry and quarrels between heralds.

Related publications

Learn more in Heralds and Heraldry in Shakespeare’s England, edited by co-curator Nigel Ramsay and available at the Folger Shop.

This is a lavishly illustrated collection of essays about most of the main themes of the show, ranging from the heralds themselves to grants of arms, heraldic visitations and heraldic funerals, as well as the place of heraldry in the work of different Elizabethan and Jacobean writers.

- Heralds and Heraldry in Shakespeare’s England. Edited by Nigel Ramsay. Donington, Lincolnshire: Shaun Tyas, 2014.

- Folger Call number: CR1615 .H47 2014

Related programs

Talks and Screenings at the Folger

- Shake Up Your Saturdays: Exploring Heraldry, July 5, 2014

- "Shakespeare's Coat of Arms and the Early Modern Heraldry Wars", Kathryn Will, July 17, 2014

- Shake Up Your Saturdays: We Are Shakespeare, August 2, 2014

- "The Institute of Heraldry: Guardians of our National Symbolic Heritage", Charles Mungo, September 19, 2014

- "Heraldry and the College of Arms", Peter O'Donoghue: York Herald, October 1, 2014

Folger Theatre

- William Shakespeare's Hamlet, July 25–26, 2014

- William Shakespeare's King Lear, September 5–21, 2014

Folger Consort

- Early Music Seminar, September 24, 2014

- Courting Elizabeth: Music and Patronage in Shakespeare's England, September 26–28, 2014

Suggestions for further reading

This brief Annotated bibliography of readings related to Symbols of Honor is not meant to be comprehensive but to provide a variety of resources about heraldry.