Scholars' insights on Shakespeare's the Thing

This article explores four and a half centuries of Shakespeare with Folger staff and others close to the library as they discuss special highlights featured in Shakespeare's the Thing, one of the Exhibitions at the Folger.

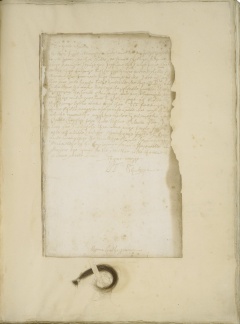

A Famous Forgery (case 1)

Heather Wolfe on William Henry Ireland.

I've always been fascinated by the fact that William Henry Ireland was able to temporarily convince the literary world that he had made the most important literary discovery ever.

William Henry Ireland was a *really bad* forger of Shakespeare manuscripts with a too-good-to-be-true story of how he came to own them. Nevertheless, he managed to capitalize upon his deceptions after he was found to be a fraud.

Case in point is this fake letter from William Shakespeare to his wife Anne Hathaway. Written in a terrible imitation of an English secretary hand and carelessly burned around the edges to appear "ye olde," this copy was actually written out by William Henry Ireland after the forgeries were discovered. It appears here next to a printed reproduction of his original forgery, in an album that he put together for a curious collector over a decade after the original forgeries were made.

Many other versions of the forgery survive, including a handful at the Folger which Ireland created both to sell and to give to supporters. This is the only one at the Folger with a lock of hair, however. We're not sure where the hair in our copy came from, but one could assume it came straight from the head of William Henry Ireland himself.

While many people initially believed that the documents were authentic, the handwriting and spelling were so unconvincing, as was their literary merit, that it soon became apparent that the entire archive had been concocted. This letter is a prime example of William Henry Ireland's flowery style leading to his own unraveling.

Heather Wolfe is Curator of Manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library. She has curated or co-curated many of the Folger exhibitions including Technologies of Writing in the Age of Print, Letterwriting in Renaissance England, Word & Image: The Trevelyon Miscellany of 1608, and The Pen's Excellencie.

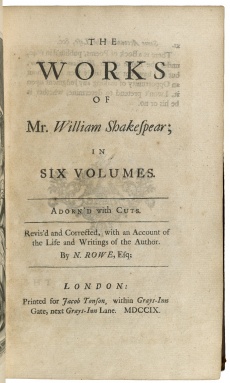

Editing Shakespeare (case 6)

Barbara Mowat on editor Nicholas Rowe.

Nicholas Rowe was a lawyer who switched careers and began writing for the London stage. When he was asked to edit Shakespeare's plays in the early 1700s, he searched everywhere for Shakespeare's manuscripts, but they had already disappeared. Rowe was thus forced to base his 6-volume edition on the early printed texts—the 36 plays collected in the 1623 First Folio and printed in the Folios that followed, as well as the few plays that he could find that had also been printed individually in small quartos. His edition, published in 1709, made the plays available and accessible to a wide readership in many ways. Among the most important: he modernized the spelling and punctuation; he occasionally replaced a word that seemed incorrect; he standardized characters' names; and he added stage directions. He also used material from quarto editions of Hamlet and Othello to add to or correct the Folio texts. His edition became the basis of subsequent texts for many years, and many of his textual corrections and his decisions about characters' names have stood for centuries.

Hear Mowat discuss this important editor.

Barbara Mowat is Director of Research emerita at the Folger. In addition, she is co-editor, with Paul Werstine, of the Folger Shakespeare Library Editions, which are the basis for the Folger Digital Texts and consulting editor for Shakespeare Quarterly.

Rival Richard IIIs (case 11)

Robert Richmond on rivals Junius Brutus Booth and Edmund Kean.

There is so much happening in this image and the more I look, the more I enjoy it. While it is open to many interpretations, my reading has always been that this piece is more than just a commentary on the storied rivalry between Junius Brutus Booth and Edmund Kean, competing in the early nineteenth-century in warring productions of Richard III. A closer look at the red-faced cigar-smoking manager, the patent clapping machine, and the box office man tallying up the take suggests a struggle with the commercialization of theatre at this time. The deeply-felt rivalry served neither actors nor audience—only the management who lined their pockets with the proceeds. And as a British-born director currently staging Richard III at the Folger, the clash between these two performers always reminds me of that familiar tussle of ownership over Shakespeare between the UK and the US. Edmund Kean was the greatest British actor of his generation; Booth, (though a native Englishman) was soon to become the most prominent actor in the United States. What I find so relevant about this "cartoon" is that here, at the Folger, I have found the place where this conflict has been fully resolved. In this remarkable institution, the universality of Shakespeare, his work, and his relevance is housed under one roof.

Robert Richmond is director of the Folger's 2014 production of Richard III. He has directed previous plays with the Folger including Twelfth Night, Othello, and Henry VIII.

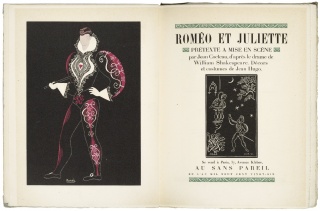

Jean Cocteau's Romeo (case 13)

Janet Griffin on Jean Cocteau's Romeo et Juliette.

Having just had Romeo and Juliet on our stage this fall, we were thrilled to see this version of Shakespeare's greatest love story. Jean Cocteau's Roméo et Juliette, a wonderful example of surrealist theatre. It relied a great deal on choreography and found meaning beyond the simple text. While we at Folger take great store by the text, this Cocteau production would certainly have been an amazing night in the theatre—and one which I would have jumped to present when it played in Paris in 1924—just 8 years before the Folger opened. I know our audience would have embraced the daring of the piece. The costumes, designed by Jean Hugo, a gifted artist of France's avant-garde and the great grandson of Victor Hugo, were impressive with their iridescent linear designs which glowed under what I suspect was the equivalent of black light—quite a psychedelic experience! This limited-edition volume with its splendid hand-colored illustrations is a testament to the remarkable ways in which great artists through time have retold Shakespeare's moving tale of woe.

Listen to Janet Griffin talk about Cocteau's production.

Janet Griffin is Director of Public Programs and artistic producer of Folger Theatre.

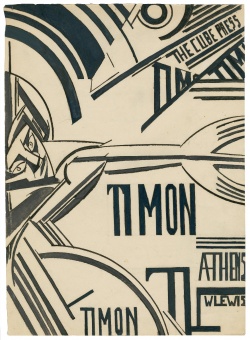

Modernist Timon of Athens (case 18)

Essence Newhoff on a Wyndham Lewis illustration for Timon of Athens.

The Folger has a strong culture of philanthropy. My job here is to match the inspired generosity of donors with the passionate work of our staff. I'm intrigued with the story of Timon of Athens, a play that, in many ways, chronicles an individual who wants to be a philanthropist, but goes about it all wrong, and is so cheated by his friends that he ends up hating all of humanity. This Wyndham Lewis illustration for the play, drawn almost exactly 100 years ago, is riveting. Lewis, along with the poet Ezra Pound, was a leader of the briefly lived but influential, London-based modernist movement known as Vorticism. The Guggenheim describes the Vorticists' style as "combining machine-age forms and the focused energy suggested by a vortex." Here you see a character, presumably Timon, with his hands outstretched. Lewis doesn't note the Act or Scene he is illustrating, so the viewer can question: is this Timon being generous and giving? Or is he trying to wring the necks of those who betrayed him (and in turn all humankind)? Are his wrists together in a symbol of his feeling shackled by his situation? It's a highly visual representation of this play, and I love peering into the moment of history when Lewis created it. You can see more of Lewis' illustrations here.

Hear Newhoff discuss this modernist interpretation of Timon of Athens.

Essence Newhoff is the the Folger Shakespeare Library's Director of Development.

Four states of Shakespeare's portrait (case 19)

Erin Blake on different "states" of the Droeshout portrait of Shakespeare.

The copper printing plate that Martin Droeshout engraved was touched up twice during the printing of the First Folio in 1623, and once more for the Fourth Folio, sixty-two years later - that is, the print exists in four different states. Although there are 4 Folios and four states of the portrait, the various states don't correspond to the editions of the Folio—states 1, 2, and 3 are all found in the First Folio.

In this case, you can see one of each of the four states.

Only four examples of the first state survive. Two are at the Folger: one still bound in the book, and the one at top left, disbound before the library purchased it. Look at the right-hand side of the collar, below Shakespeare's left ear, to spot the main difference between the first state and the rest: in state one, Shakespeare's head doesn't cast a shadow on the collar. Because so few examples exist, it's assumed that Droeshout realized pretty quickly that the portrait looked odd, so he went back and added the shadow.

The differences between the second and third states are minor: a highlight in each pupil and an extra strand of hair.

But the fourth state is heavily re-engraved. Droeshout's original lines grew shallower as the plate wore out, so they held less ink, and printed thinner and paler. Whoever touched up the plate in 1685 used cross-hatching to darken it. Look at the facial hair in state 4, and you can see how the wavy lines making up Shakespeare's moustache and soul patch now have diagonal slashes across them.

Hear Erin Blake describe the differences in the four Droeshout versions.

Erin Blake is Curator of Art & Special Collections at the Folger Shakespeare Library. She has co-curated many previous Folger exhibitions including The Curatorial Eye: Discoveries from the Folger Vault, Word & Image: The Trevelyon Miscellany of 1608, Fakes, Forgeries & Facsimiles, and David Garrick, 1717–1779: A Theatrical Life.