Thys Boke is Myne

Thys Boke is Myne, part of the Exhibitions at the Folger, opened on November 13, 2002 and closed on March 1, 2003. Major support for this exhibition came from The Winton and Carolyn Blount Exhibition Fund.

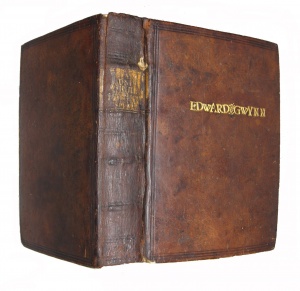

Thys Boke Is Myne is about provenance—the relationship between people and their books through five hundred years of printing history. The exhibition explores how bibliophiles, famous and forgotten, have signaled ownership of treasured volumes, revealing something of their character in the process. Books belonging to writers, collectors, royalty, actors, statesmen and women are on display, setting out the interesting and amusing ways people connect with their books. Inscriptions, mottoes, manuscript additions, bookplates, book labels, armorials, and binding stamps link texts to their owners from William Caxton to Langston Hughes. Its title is taken from a line writ large in Henry VIII's schoolboy copy of Cicero, which reads "Thys Boke Is Myne Prynce Henry."

Curation

Thys Boke is Myne was curated by Richard Kuhta. Richard received his B.A. at Swarthmore College in English Literature and completed his graduate studies at the Shakespeare Institute (England) and Trinity College Dublin (Ireland). After receiving a Masters in Library Service from Columbia University, he has worked as a library administrator in academic and research institutions for the past twenty years, with accomplishments in developing and implementing programs in reader services, with initiatives focused on conservation and special collections, and in library automation. Most recently, he has written and lectured on printing history in the Irish Literary Renaissance (Cuala Press), and the paintings of Henry Fuseli, a late-eighteenth century artist of Shakespearean themes, as well as doing consulting work in the field of library automation.

Richard was University Librarian at St. Lawrence University from 1986-1994, where he presented the prestigious Frank P. Piskor Faculty Lecture in 1994. He was appointed Librarian of the Folger Shakespeare Library in February 1994.

Curator's insights

Writers' Reading

Writers' marks are especially interesting. Authorial inscriptions tell us about personal relationships and document variations in handwriting or signature. Annotations record reactions to the competition, reflect prejudices, or show an author being difficult or vulnerable—in short, human. Reconstructing the contents of a writer's library can reveal source material behind famous works, or produce wonderful stories. Dr. Johnson, "though he loved his books, did not show them respect," says Boswell. He did not hesitate to slice leaves from a book with a greasy knife, or read while he ate, "and one knows how he ate." John Locke's library was a masterpiece of order, while Oliver Goldsmith and John Ruskin mutilated their books, tearing out chapters to avoid transcription, or giving choice pages to friends. It is riveting to see copies we know were owned by John Dryden, Edmund Spenser, or embellished with verse by Langston Hughes. These books exude an extra quality of life, like seeing a love letter.

I am Myles Blomefylde's booke

While it is thrilling to see books owned by Donne, Sidney, and Jonson, "nobodies" owned books in the early modern period, too. In Tudor England, reading and ownership was not limited to the rich and famous. The case "Quiet Lives" tells about the private libraries of people who cannot be found in the Dictionary of National Biography, people whose only evidence of existence is found in the books they left behind. Consider Myles Blomefylde, virtually unknown, who communicated with his books. "I am Myles Blomefylde's booke" they responded—one of the favorite inscriptions on display.

Women's Libraries

Scholarship is revealing much about women and their reading habits, and the exhibition shows you some of the books they owned. Frances Wolfreston (1607-1677) had a library of over 400 volumes and almost all have her signature, Frances Wolfreston, her bouk carefully written with a thick quill pen. Wolfreston's interest in drama and contemporary English literature was probably unusual for her time, but she acquired some the greatest rarities of early English literature. She had no less than ten Shakespeare quartos, a copy of the Rape of Lucrece (1616), and history is indebted to her for the first edition of Venus and Adonis (1593), a unique copy later owned by Edmund Malone and now in the Bodleian. Did any woman collect more Shakespeare in the 17th century?

I must first confess my want of Books.—Sir Walter Raleigh

Thys Boke Is Myne shows you volumes belonging to some of the greatest collectors in the early modern period (John Dee, Edward Dering, Thomas Knyvett, John Lumley), and books from renowned family libraries, like the one at Britwell Court, said to have rivaled or even surpassed the British Museum. The 18th century was an age of great collectors as well as great actors and editors of early drama, roles sometimes played by the same person. David Garrick's library was unsurpassed. John Philip Kemble's was a model of scholarly care. George Steevens and Edmund Malone, known more for being devoted editors of Shakespeare, battled each other in the auction rooms.

Thys Boke was Pope's?

The monetary value of a book may depend on who has owned it, and the evidence of ownership is a subject of the exhibition. Ordinary copies become unique when we know they were annotated by Anne of Cleves, George Eliot, or Walt Whitman. They become treasures when we can trace bindings to the private libraries of William Cecil, Edward de Vere, or King James I. But establishing proof of ownership is not always easy and the exhibition presents some puzzles for viewers to consider. We ask you to decide, for example, whether the Folger owns Alexander Pope's copy of a Third Folio or Sir Walter Raleigh's personal copy of his monumental History of the World, written while he was held captive in the Tower of London.

When ye lok on this remember me.—Anne of Cleves to Henry VIII

Inscriptions in books are full of anecdote and human interest, and the study of provenance brings us closer to people and their history. Behold Anne of Cleves' gentle inscription to her future husband, when ye loke on thys remember me, in sharp contrast to Henry's VIII's pronouncement, Thys Boke Is Myne Prynce Henry. Somehow we know more about these human beings by the way they wrote in their books.

This exhibition is a celebration of the history of private libraries, of people and their books. Petrarch (whose private library provided the nucleus of the future Bibliothèque Nationale) praised his books as "welcome, assiduous companions, always ready…to encourage you, comfort you, advise you, reprove you and take care of you, to teach you the world's secrets…and never bring you…lamentation, jealous murmurs, or deception." That's why we own books and keep them close, that's what Thys Boke Is Myne is about.