Now Thrive the Armorers: Arms and Armor in Shakespeare

Now Thrive the Armorers: Arms and Armor in Shakespeare, one of the Exhibitions at the Folger opened on June 5, 2008 and closed on September 6, 2008. The exhibition was curated by Jeffrey Forgeng of the Higgins Amory Museum with assistance from Bettina Smith of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Arms and armor feature prominently in Shakespeare’s plays, as emblems of identity, as objects of display, and as implements of conflict. The clash of swords, the clank of armor, the roar of cannon reverberate through the texts, heightening the urgency, tension, and drama during critical scenes. The role of armor was undergoing a complex transition in Shakespeare’s day. The production of plate armor was at its peak, yet soldiers were shedding their armor on campaign. Firearms were increasingly dominant on the battlefield, and it was becoming impossible to wear armor heavy enough to stop a musketball. Those in power scrambled to ensure production of the new gunpowder weapons, while lamenting the resulting decline of traditional chivalric values. Armies once led by armored knights now looked more like modern military bureaucracies. In civilian life, private duels and armed insurrections were seen as serious threats to social stability. Yet in reality, state power and popular opinion were together undermining the private use of violence that had once been accepted as a birthright of the medieval warrior aristocracy.

Including books from the Folger collection, this exhibition features a large selection of some of the most important arms and armor from the Higgins Armory Museum in Worcester, Massachusetts. Together they capture an era in which the nature of warfare was rapidly changing yet the chivalric ideal still retained a powerful hold on the Renaissance imagination.

Listen to Gail Kern Paster, former director of the Folger Shakespeare Library discuss the exhibition, Arms and Armor in Shakespeare, in this podcast.

Exhibition material

- Daniel Mytens. Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton. Painting, after 1620. Call number: FPb55 and LUNA Digital Image.

- LOAN from Higgins Armory Museum, Worcester, MA. Fingered gauntlet of Prince (later King) Philip of Spain (1527-1598), by Desiderius Helmschmid (1513-1578/79) and Jörg T. Sorg the Younger (c. 1525-1603), steel; gold; brass; leather. The John Woodman Higgins Collection, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA. 2014.1155.14

Rites Of Knighthood: Richard II

- BOLINGBROKE: Pale trembling coward, there I throw my gage [gauntlet],…

- If guilty dread have left thee so much strength

- As to take up mine honor's pawn, then stoop.

- By that and all the rites of knighthood else

- Will I make good against thee, arm to arm,

- What I have spoke or thou canst worse devise.

- (Richard II, 1.1.71-79)

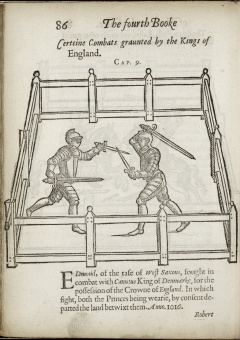

Richard II is one of the earliest of Shakespeare’s "history plays." These plays tell the story of the Wars of the Roses, the civil war between the rival royal families of Lancaster and York, which began in 1422 and ended in 1485 with the death of Richard III. The overthrow of Richard II in 1399 set the scene for this conflict. A duel between two nobles is at the center of Richard’s fall from power. Young Henry Bolingbroke, the king’s cousin, accuses the Duke of Norfolk of diverting military funds for his own use, and of taking part in the conspiracy that killed the Duke of Gloucester. In accordance with the laws of chivalry, Bolingbroke throws down his gauntlet, challenging Norfolk to an armored duel. Norfolk accepts, and the king sets a date for the encounter. The duel is about to begin when Richard throws down his baton of office on the field of combat and calls a halt to the proceedings. Wishing to avoid bloodshed, the king instead banishes the combatants: Bolingbroke for ten years, Norfolk for life. During Bolingbroke’s absence, the king takes over Bolingbroke’s inheritance, compelling him to topple the king upon his return.

Richard tries to play the part of an absolute monarch—a “Renaissance king” —by asserting control over the historically independent body of feudal knights that descended from medieval warriors. However, by denying Bolingbroke and Norfolk their duel, and by robbing Bolingbroke of his inheritance, Richard falls afoul of the rites of knighthood. The delicate fabric of feudal kingship begins to unravel, and for the next hundred years, rival branches of the royal family struggle over the English throne.

Listen to Bettina Smith discuss chivalry and dueling.

Items included

- Richard Jones. The booke of honor and armes. London: Printed by [Thomas Orwin], 1590. Call number: STC 22163 copy 1 and LUNA Digital Image.

- LOAN from Higgins Armory Museum, Worcester, MA. "Rowel" spur, Western Europe, 1625-1650. The John Woodman Higgins Collection, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester MA. 2014.980.1

Now Thrive The Armorers: Henry V

Medieval feudalism existed to put armies on the field of battle. In Henry V, Shakespeare shows us medieval English warfare at the height of its success, during the Hundred Years’ War against France (1337–1453). As the play begins, the French king denies King Henry his feudal lands. Henry responds by mustering an army to invade France, leading his followers toward the English-held port of Calais. They are overtaken by the French at Agincourt, the scene of one of the greatest upsets in military history. Although the English were outnumbered nearly 4 to 1, weather and terrain favored English defensive tactics, based on lowly longbowmen supported by a sprinkling of dismounted knights. Showers of English arrows goaded the heavily-armored French knights into riding past their own archers and crossbowmen to attack across the narrow and muddy field. Archery and mud took their toll on the attackers, and by the time the French knights reached the English line, they had lost all impetus and cohesion. The English counterattack brought a decisive victory: French casualties numbered as many as 5,000 men, while the English lost only 200.

The stars of the medieval battlefield were the mounted knights, yet by Henry V’s day, the outcome of battle was more often determined by the foot soldiers. The French defeat at Agincourt reflected a military system that emphasized cavalry over infantry, and was much better suited for attack than defense. At Castillon in 1453, the tables were reversed. An English relief force under John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, tried to break the French siege of Castillon. When Talbot’s horsemen assaulted an entrenched French position, they were shattered by the defending crossbows and by a newcomer on the medieval battlefield: the cannon. Talbot was among the slain, struck down by a French axe. The sword on display was dropped in the river Dordogne by an Englishman fleeing from the battle—the final chapter of the Hundred Years’ War.

Listen to curator Jeffrey Forgeng discuss a sword from the around 1600.

Items included

- Johann Jacobi von Wallhausen. Manuale militare, oder Kriegss manual. Frankfurt am Mayn, 1616. Call number: 181820 and LUNA Digital Image.

Draw If You Be Men: Romeo And Juliet

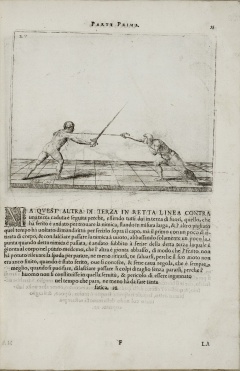

During the sixteenth century, fashionable young men took to wearing the new style of sword called a rapier as part of their everyday attire. Rapiers could be made longer and thinner than battlefield swords, since they did not have to stand up to the same kind of punishing use. Spanish and Italian fencing masters began to explore new styles of swordsmanship to suit the new weapon, developing elegant systems of combat that emphasized thrusting attacks that took advantage of the rapier’s length and lightness.

By the sixteenth century, a heated debate had arisen in England over the new weapon and its techniques. Traditionalists favored the old-fashioned broad-bladed sword, with its reliance on hewing attacks with the edge. But many style-conscious young gentlemen picked up a rapier and turned to the newer Italian style of combat.

As a result of the rapier’s popularity, the streets of London thronged with boisterous young men wearing swords at their sides. In an age where honor was everything, weapons were often drawn at the slightest provocation leading to increased civilian violence. To make matters worse, the thrusting technique of the Italian style was highly lethal. Where the traditional cutting sword tended to deal wounds that were bloody but not fatal, the rapier was designed to pierce the head or torso, where even a small puncture might lead to death. Contemporary fears about escalating violence heavily inform Romeo and Juliet, written at the height of the rapier debate in England.

To learn more about swords in Shakespeare, watch this video.

Items included

- Salvator Fabris. De lo schermo o'vero Scienza d'arme. Copenhagen, 1606. Call number: Folio U860 F3 1606 Cage and LUNA Digital Image.

To See A Good Armor: The Armorer's Craft in Shakespeare's Day

- BENEDICK: I have known when there was no music

- with him but the drum and the fife, and now had he

- rather hear the tabor and the pipe; I have known

- when he would have walked ten mile afoot to see a

- good armor, and now will he lie ten nights awake,

- carving the fashion of a new doublet.

- (Much Ado About Nothing, 2.3.13-18)

By Shakespeare’s day, the medieval craft of armor-making had become a modern industry. Governments engaged contractors who promised to deliver the equipment, and the contractors tapped a network of smaller suppliers to make up the thousands of orders it took to supply an army. The iron came from continual-production blast furnaces that melted iron ore to extract the metal. The iron was hammered into flat sheets by water-powered triphammers, manned by low-paid laborers. At the end of the process, the armor was finished with water-powered grinding and polishing wheels.

Despite these advances, the central stage of armor production remained very much a craft. The armorer trained for about seven years as an apprentice, learning the subtle art of shaping steel to accommodate the complex shapes and motions of the human body. The final product had to be strong enough to resist battlefield damage, flexible enough to allow almost total freedom of movement, and stylish enough to meet the tastes of fashion-conscious Elizabethans.

Listen to curator Jeffrey Forgeng discuss extremely high status suit of armor.

Items included

- Hartmann Schopper. Panoplia omnium illiberalium mechanicarum aut sedentariarum artium genera continens. Frankfurt, [1568]. Call number: GT5770 S4 Cage and LUNA Digital Image.

- Jan. Collaert after Jan van der Straet. Politura armorum from Nova reperta. Engraving. [Antwerp], [between 1636 and 1677] . Call number: ART Vol. f81 no.17 and LUNA Digital Image.

Brave New World: The Tempest

- GONZALO: Had I plantation of this isle, my lord—…

- I' th' commonwealth I would by contraries

- Execute all things, for no kind of traffic

- Would I admit; no name of magistrate;

- Letters should not be known; wealth, poverty,

- And use of service, none; contract, succession,

- Bourn, bound of land, tilth, vineyard, none;

- No use of metal, corn, or wine, or oil;

- No occupation, all men idle, all,

- And women too, but innocent and pure:

- No sovereignty—

- …All things in common nature should produce

- Without sweat or endeavor; treason, felony,

- Sword, pike, knife, gun, or need of any engine

- Would I not have; but nature should bring forth

- Of its own kind, all foison [bounty], all abundance

- To feed my innocent people.

- …I would with such perfection govern, sir,

- T'excel the Golden Age.

- (The Tempest, 2.1.157-185)

Inspired by the story of a Bermuda shipwreck in 1609, The Tempest explores the complexities of planting a “brave new world” on foreign soil. Like the shipwrecked counselor Gonzalo, Europeans dreamed of the possibilities in this seeming Garden of Eden: a landscape unspoiled by human exploitation, a people free of class divisions, and a culture without implements of war. Yet like the magician Prospero, the Europeans came to their new home with an instinct for power and with secret knowledge that would help them acquire it—especially the technologies of steel and gunpowder that lay at the foundation of the European military system.

Items included

- LOAN from Higgins Armory Museum, Worcester, MA. Root club, Southeastern Pennsylvania, late 19th - early 20th century. Higgins Armory Museum, Worcester MA.

Imagining Some Fear: A Midsummer Night's Dream

- THESEUS: The poet's eye, in a fine frenzy rolling,

- Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven

- And as imagination bodies forth

- The forms of things unknown, the poet's pen

- Turns them to shapes, and gives to airy nothing

- A local habitation and a name.

- Such tricks hath strong imagination

- That, if it would but apprehend some joy,

- It comprehends some bringer of that joy;

- Or in the night, imagining some fear,

- How easy is a bush supposed a bear!

- (A Midsummer Night’s Dream, 5.1.12-23)

Far from being simply tools of warfare, arms were powerful emblems of personal identity. They were also equally powerful as transformative trappings, capable of converting the wearer into a figure strange, exotic, and eye-catching. Representations of arms and armor—and the artifacts themselves—show the fantastic imagination of the Renaissance in full play. Today we think of armaments as technologies designed for brutal efficiency. Yet this was certainly not the case in Shakespeare’s day. The clients who purchased arms and armor valued the same kind of fanciful creativity in the craftsman’s wares as they enjoyed in a play like A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Listen to Jeffrey Forgeng discuss the embossed details of a ceremonial breastplate.

Items included

- LOAN from Higgins Armory Museum, Worcester, MA. Ceremonial breastplate, France, 1550-1575. The John Woodman Higgins Collection, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA. 2014.70.1

Our Legions Are Brim Full: Julius Caesar

- BRUTUS: Our legions are brim full, our cause is ripe.

- The enemy increaseth every day;

- We, at the height, are ready to decline.

- There is a tide in the affairs of men

- Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

- Omitted, all the voyage of their life

- Is bound in shallows and in miseries.

- On such a full sea are we now afloat;

- And we must take the current when it serves,

- Or lose our ventures.

- (Julius Caesar, 4.3.246-255)

To Renaissance Europeans, the story of ancient Rome was a matter of immediate modern relevance. Political leaders saw the rise and fall of figures like Caesar as timeless lessons about how power can be gained or lost. Military commanders studied Caesar’s armies and campaigns as models to guide modern military practice. Artists, poets and playwrights found in the Roman heritage a rich vocabulary to enrich their own contemporary creations. Rome’s enduring importance is reflected in the arms and armor of Shakespeare’s day. Classical themes feature prominently in the decoration and design of armor. The decorative motif on the Medici backplate derives from the ancient Roman “trophy”: armor and weapons displayed as spoils stripped from defeated enemies after a victory in battle. The morion-burgonet imitates a style associated with the ancient Romans: its wearer, like Louis XIII as represented in Valdor’s image, was appropriating the power and sophistication that Renaissance Europeans associated with Rome’s classical age.

Items included

- Jean Valdor. Les triomphes de Louis le Iuste XIII. du nom, roy de France et de Nauarre. Paris, 1649. Call number: 222- 718.1f; displayed p. 79, "Perpignan".

'Tis The Soldier's Life: Othello

- OTHELLO: Come, Desdemona. 'Tis the soldier’s life

- To have their balmy slumbers waked with strife.

- (Othello, 2.3.276-277)

- To have their balmy slumbers waked with strife.

The story of Othello reflects the changing world of Renaissance warfare. By Shakespeare’s day the armored horsemen of the medieval battlefield had lost much of their effectiveness in the face of improved infantry equipment and tactics. Armor was still common, but as firearms became more powerful and reliable, armor had to be made thicker and heavier to withstand them. The extra weight became excessive, and soldiers began to abandon parts of their armor, keeping only the protection for their head and torso.

Armies no longer consisted of feudal knights and peasants, but of full-time professionals. These long-term professional soldiers developed a culture of their own that was increasingly separated from the culture of the civilian world and distinct from the traditional concepts of chivalry and feudalism.

The tragedy of Othello is heavily informed by the emerging professional world of the Renaissance soldier, set against the backdrop of the Venetian garrison on Cyprus. Othello has chosen the bookish Florentine Cassio for his second-in-command, appointing his old comrade-in-arms Iago as ensign (standard-bearer); an honorable position, but without real authority. Iago's fury at this slight takes itself out on Desdemona, who has joined her new husband amidst the garrison. Desdemona's story is played out in this alien world of the military camp. She is cut off from the usual civilian and female networks on which she might normally rely.

Listen to curator Jeffrey Forgeng discuss professional armies.

Items included

- Francesco Fernando Alfieri. La Picca, e la Bandiera. Padua, 1641. Call number: 186-963q and LUNA Digital Image.

Armed at Point Exactly: Hamlet

- …a figure like your father,

- Armèd at point exactly, cap- â-pie,

- Appears before them and with solemn march

- Goes slow and stately by them. Thrice he walked

- By their oppressed and fear-surprisèd eyes,

- Within his truncheon's length…

- (Hamlet, 1.9.209-214)

Shakespeare’s most famous tragedy dramatizes the historic shift from the medieval ideals of chivalry to Renaissance Machiavellianism. Hamlet’s father is remembered as an impetuous warrior who personally overcame his enemies in hand-to-hand combat. Hamlet’s uncle Claudius is very different: a Renaissance ruler who uses politics, diplomacy, and even assassination to obtain his ends. Young Hamlet is caught in the middle of this transition, a philosopher-prince who is neither a medieval-style knight like his father nor a politician like his uncle.

Each of the three is associated with arms that powerfully evoke their personalities. The ghost of the elder Hamlet appears in cap-â-pie armor—“head to toe,” the typical style of a medieval knight, but no longer the norm in Shakespeare’s day. Claudius is characterized by the artillery that manifests his royal authority, and by the “Switzers” (mercenary soldiers) on whom he relies for protection. Young Hamlet, aptly, is master of the rapier, the cerebral Italian weapon whose techniques were grounded in Renaissance science and geometry.

Hamlet explores the making and unmaking of kings in ways that closely associate them with the father-son relationship and with the building of masculine identities. The elder Hamlet is a king—and a man—of the old school: quick to anger, fierce in battle, committed to revenge. His son is a figure of a different stamp. University-educated, skilled in the modern art of fencing, interested in theater, and naturally philosophical, young Hamlet is very much a Renaissance man. Claudius contrasts with both his brother and nephew: neither truly a warrior nor truly a scholar, Claudius excels in the manipulation and exercise of power

Items included

- LOAN from Higgins Armory Museum, Worcester, MA. Siege helmet, England [?], 1600-1650. The John Woodman Higgins Collection, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA. 2014.1125

Supplemental material

Arms and Armor in Shakespeare children's exhibition

About the Higgins

The Higgins Armory Museum is the only museum dedicated exclusively to armor in the Western hemisphere.

The museum was founded in 1931 by John Woodman Higgins, a wealthy industrialist and avid collector of armor.

As a young man, Higgins (1874-1961) had a passion for medieval tales about knights and castles. Growing up in late nineteenth-century Worcester, MA, then a leading center of American manufacturing, he observed blacksmiths, factory workers, and entrepreneurs, and developed an interest in metalworking and industry. These two passions would merge in the Higgins Armory Museum.

Today,[1] Higgins’s legacy lives on in the museum’s collection of over 5000 artifacts, centering on the armor and arms of the Middle Ages and Renaissance, and including comparable pieces from the ancient period and from around the world. You can search the collection online through the Worcester Art Museum catalog.

- ↑ In December 2013, the Higgins Armory Museum closed. Its entire collection is now housed at the Worcester Art Museum. To learn more about the integration, read this article.

Audio

Explore Arms and Armor in Shakespeare on an audio tour.

Family Ties

Listen to Bettina Smith discuss the Paul Hector Mair's Book of Dynasties.

- Paul Hector Mair. Geschlechter Buch: darinn der loblichen kaiserliche[n] Reichs Statt Augspurg so vor fünffhundert vnd mehr Jaren hero, daselbst gewonet, vnd biss auff acht abgestorben, auch deren so an der abgestorbnen stat eingenom[m]en vnd erhöhet worden seyn : dessgleichen mit was Personen die Röm. Frankfurt, 1580. Call number: 239- 584f and LUNA Digital Image.

The Bodyguard

Listen to Jeffrey Forgeng discuss a halberd.

- LOAN from Higgins Armory Museum, Worcester, MA. Bodyguard halberd, Germany, 1611. The John Woodman Higgins Collection, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester MA. 2014.129

Warfare 101

Listen to Bettina Smith discuss jousting and military manuals.

- Johann Jacobi von Wallhausen. Manuale militare, oder Kriegss manual. Frankfurt am Mayn, 1616. Call number: 181820 and LUNA Digital Image.

Child's Play

Listen to Jeffrey Forging discuss armor made for children.

- LOAN from Higgins Armory Museum, Worcester, MA. Child's fingered gauntlet, Germany, 1560-1570. The John Woodman Higgins Collection, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester MA. 2014.570

Fit for a Prince

Listen to Jeffrey Forgeng discuss a high-end gauntlet fit for Prince Philip of Spain.

- LOAN from Higgins Armory Museum, Worcester, MA. Fingered gauntlet of Prince (later King) Philip of Spain (1527-1598), by Desiderius Helmschmid (1513-1578/79) and Jörg T. Sorg the Younger (c. 1525-1603), steel; gold; brass; leather. The John Woodman Higgins Collection, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA. 2014.1155.14

A Commanding Figure

Listen to Virginia Millington discuss a painting of Henry Wriothesley, the Third Earl of Southampton.

- Daniel Mytens. Henry Wriothesley, Third Earl of Southampton. Painting, after 1620. Call number: FPb55 and LUNA Digital Image.

Flourishing the Flag

Listen to Virginia Millington discuss Alfieri's swordsmanship manual.

- Francesco Fernando Alfieri. La Picca, e la Bandiera. Padua, 1641. Call number: 186-963q and LUNA Digital Image.

A Case of Partisanship

Listen to Jeffrey Forgeng discuss the role of partisan swords in protection.

- LOAN from Higgins Armory Museum, Worcester, MA. Head of a Partisan for the Guard of Henri III of France (r. 1574-89). Bodyguard partisan, France, 1588. The John Woodman Higgins Collection, Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA. 2014.44

A Show of Force

Listen to Virginia Millington discuss Valdor's work honoring King Louis XIII.

- Jean Valdor. Les triomphes de Louis le Iuste XIII. du nom, roy de France et de Nauarre. Paris, 1649. Call number: 222- 718.1f; displayed p. 79, "Perpignan".

Video

Join curator Jeffrey Forgeng for video tour of the exhibition highlights. We've created two short videos on two of the exhibition's major themes.

The first, "Swords and Shakespeare," showcases weapons of Shakespeare's day and how changes in weaponry profoundly impacted plays such as Romeo and Juliet and Othello.

The second video, "Dressed to Thrill," explores how knights needed armor for both fashion and function.