Impressions of Wenceslaus Hollar

Impressions of Wenceslaus Hollar was part of the Exhibitions at the Folger, and opened on September 25, 1996, and closed on February 3, 1997.

The exhibition catalog can be purchased from the Folger Shop.

If Wenceslaus Hollar were alive today, he might well be a freelance photographer. His eye was his camera lens, his copperplates the film. No other artist recorded so many aspects of seventeenth-century English life as he did.

Over some forty years and in more than 2700 etchings, he covered a vast array of subjects for his patrons, for the publishers, and in collaboration with other artists: architectural and topographical views, maps, copies of paintings and drawings, and depictions of people, fashions, and events. His harmonious landscapes and precise architectural renderings, his dazzling studies of women's costume, and his vivid depictions of crowds of people are remarkable for their virtuosity and detail.

Impressions of Wenceslaus Hollar is about Hollar's impressions of he world in which he lived, how he saw that world, what captured his attention, and his imagination, and what he was commissioned to see and record. Nearly 150 of the 1400 Hollar etchings in the Folger Library collection have been included in this exhibition in order to represent aspects of Hollar's career, from his travels in Germany in the 1630s, through his years in England, in Antwerp, and in England again, until his death in 1677.

Impressions of Wenceslaus Hollar also reflects our impressions, our responses to the artist who was nearsighted and used "a glasse to helpe his sight," yet etched such delicate lines that often we need a magnifying glass to see them; the talented copyist, who could reproduce another artist's work and record a landscape or a building, but could not quite master the contours of a human face; the man who was captivated by lace and fur, by texture and lines, and yet eschewed baroque exaggeration in favor of simplicity and clarity.

Exhibition material

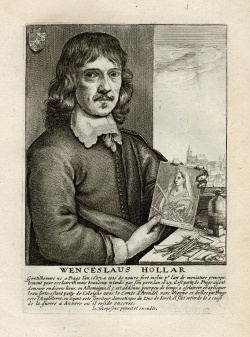

- Wenceslaus Hollar. Wenceslaus Hollar. From Jean Meyssens, Image de divers hommes d'esprit sublime. Antwerp, 1649. Displayed portrait.

The Road from Prague: Hollar's Early Years

Hollar was born in Prague in 1607. At the age of twenty he left Bohemia. After travels in Germany, he journeyed to England in 1636 as the protegé of the Earl of Arundel who engaged Hollar to etch copies of artworks in his collection. It was Arundel's desire, apparently, to create a visual inventory of his collection, a "paper museum" of etchings that would be an enduring record. Although Arundel's plan was never completed, there are numerous etchings by Hollar that are our only remaining record of works of art in the collection.

Hollar's fascination with texture and skill at reproducing it in the etched medium are among his most notable characteristics. His interest in costume began in Germany and continued in England. The Ornatus Muliebris Anglicanus, or The Severall Habits of English Women and the Seasons, published in the 1640's, demonstrate Hollar's talents as a miniaturist. His ability to capture the play of light on shimmering gowns and the exquisite detail of lace and furs is evident in this three-quarter length figure of Spring.

This case included

- Wenceslaus Hollar. Spring from The Four Seasons. London, 1641. Call number ART 252-175.1 (size M) ; displayed print.

From London to Antwerp

The Earl of Arundel left England in February of 1642, only months before the continuing conflict between king and parliament escalated into serious military confrontation. Hollar, however, remained in London where he produced cheap, crude illustrations for the flourishing popular press. In 1644 he moved to Antwerp and, over the next eight years, refined his talents, producing what are considered some of his greatest etchings.

Hollar's sources were varied. He etched plates from sketches he had made in England, and he copied prolifically from the works of Durer, Van Dyck, Holbein, Titian, and others. His portrait of a woman with coiled hair after Durer was issued in Antwerp in 1646 and was based on a painting in the Arundel collection. Some of his scenes, portraits, and representations from life are beautifully conceived and sensitively executed. These include the below portrait of a young African woman.

This case included

- Wenceslaus Hollar. Woman with coiled hair. London, 1646. Call number ART Box H737.5 no. 26; displayed print.

- Wenceslaus Hollar. Portrait of a young African woman. Etching, 1645. Call number ART Vol. b35 no. 46; displayed plate no. 46.

England Again: From 1652 to 1677

Hollar returned to England in 1652 and began working for the publisher John Ogilby and the antiquary Sir William Dugdale. Over the next twenty-five years he etched no fewer than 566 plates for them.

He produced many precise architectural renderings and topographical views for Dugdale's Monasticon Anglicanum (1655-1673). On his view of the east end of Lincoln Cathedral, prepared for volume 3 of Dugdale's Monasticon, Hollar signed himself "Scenographer Royal." Charles II had granted him the title following the Great Fire of 1666 in recognition of Hollar's work documenting parts of the city of London before and after its destruction.

Hollar's ultimate ambition to create a map of the city measuring ten feet by five feet was never realized. In a bid to secure subscriptions to finance the project, Hollar issued a prospectus describing his plans. The only surviving copy of "Propositions Concerning the Map of London and Westminster" is in the Folger Library. It served as a receipt to Sir Edward Walker for his subscription and bears Hollar's signature.

Wenceslaus Hollar died in London in 1677. The young Czech artist that the Earl of Arundel took to England in 1636 had spent forty years recording his impressions of the turbulent era in which he lived. His etchings permit us to witness the spectacle of coronations and executions, to pour over the detail of costumes, and to view a terrain that was shifting even as Hollar rendered it and that has since been irrevocably altered. Treasures from the Arundel art collection, buildings such as St. Paul's, and the city of London that Hollar knew, in the words of his contemporary, John Aubrey, "live now only in Mr. Hollar's etchings." The Earl of Arundel's "paper museum "took shape in the larger vision of the seventeenth-century antiquaries and in the visual documentation Wenceslaus Hollar provided for them.

This case included

- Wenceslaus Hollar. East end of Lincoln Cathedral. From Sir William Dugdale, Monasticon Anglicanum, vol. 3. London, 1673. Call number 152-273f Vol. 3; displayed second plate after page 256.