The Ashbourne portrait: Difference between revisions

SophieByvik (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

SophieByvik (talk | contribs) (added image of portrait) |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

==Physical description== | ==Physical description== | ||

[[File:FPs1.jpg|thumb|right|300px]] | |||

The portrait was completed in 1612, though its initial painter remains unknown. William L. Pressly has tied the figure's pose to another anonymous work of the seventeenth century, a 1614 portrait of Sir Thomas Broderick, who is displayed in the same three-quarter pose beside a skull as Sir Hugh Hamersley.<ref>William L. Pressly, "The Ashbourne Portrait of Shakespeare: Through the Looking Glass," ''Shakespeare Quarterly'' 44 (1993): 68.</ref> | The portrait was completed in 1612, though its initial painter remains unknown. William L. Pressly has tied the figure's pose to another anonymous work of the seventeenth century, a 1614 portrait of Sir Thomas Broderick, who is displayed in the same three-quarter pose beside a skull as Sir Hugh Hamersley.<ref>William L. Pressly, "The Ashbourne Portrait of Shakespeare: Through the Looking Glass," ''Shakespeare Quarterly'' 44 (1993): 68.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 13:18, 22 July 2015

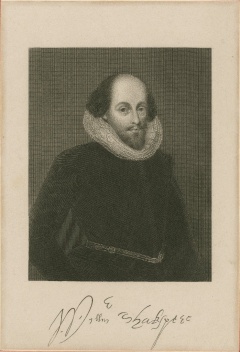

Once thought to be a portrait of William Shakespeare, and now known to depict the slightly altered visage of Sir Hugh Hamersley (1565-1636), the Ashbourne portrait has been the locus of scholarly and popular debate since its discovery in 1847. It joined the Folger collection in 1931 as a portrait of Shakespeare in preparation for the opening of the Folger Shakespeare Library. For more information, see this item's Hamnet record.

Physical description

The portrait was completed in 1612, though its initial painter remains unknown. William L. Pressly has tied the figure's pose to another anonymous work of the seventeenth century, a 1614 portrait of Sir Thomas Broderick, who is displayed in the same three-quarter pose beside a skull as Sir Hugh Hamersley.[1]

Alterations to the painting

Pressly has speculated that, while the portrait's transformation from Hamersley to Shakespeare cannot be fully traced, it is likely that the Rev. Clement Kingston, who initially acquired the painting in 1847, executed the changes. Kingston, a teacher, was cited by a former student as an artist. [2] Changes essential for the transformation of Sir Hugh Hamersley to William Shakespeare included: painting over the coat of arms, changing the inscribed date from 1612 to 1611, and raising the Hamersley hairline to resemble that of the balding Shakespeare of the Droeshout portrait.

Conservation

In 1932, most of the paintings in the Folger collection were cleaned or relined in preparation for the opening of the Library. It is likely, but ultimately unknown, that the Ashbourne portrait was tended to in this group. In 1936, an Oxford newsletter references the portrait being cleaned and varnished by the Fogg Museum, though neither the Fogg nor the Folger have records of this exchange; if any work was completed on the portrait during the 1930s, it was probably done in 1932 with the rest of the Folger collection by conservators from the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

In 1950, the portrait was X-rayed by the National Gallery of Art, whose restorer, Stephen S. Pichetto, determined that the original painting was completed no earlier than the second half of the 17th century, and the overpainting completed no earlier than the 18th century. The painting was examined in 1963 by David Piper of London's National Portrait Gallery (see above). In 1979, Peter Michaels made more extensive restorative changes to the painting, removing a layer of varnish and two layers of dark background paint. It was relined once more. Arthur Page continued restorative work in 1988 and 1989, removing Michaels' restoration and re-cleaning and re-lining the painting. In 2000, Page revarnished the portrait.

A 2002 examination of the portrait by the Canadian Conservation Institute found no "C.K." monogram below the coat of arms.

Controversy

Portrait painter Abraham Wivell verified the image soon after the Reverend Clement Usill Kington's acquisition of it in 1847; in December of that year, a mezzotint made the no-longer-supposed portrait of playwright William Shakespeare available to the public.[3] For the duration of the nineteenth century, the portrait was lauded as a dignified image of England's greatest poet. M.H. Spielmann was the first scholar to dispute the identity of the sitter in a 1910 article. Spielmann dispensed with much of the evidence that had previously been used as identifying proof of Shakespeare: the crest on the book held by the sitter was not Shakespeare's; though Shakespeare had appeared at court, this did not guarantee that he ever wore courtly dress; the sitter was not presented in stage dress and thus could not be a depiction of the playwright as Hamlet (a theory favored based on the skull that sat on the table in the portrait's lower left corner). Spielmann, however, ultimately remarked that the sitter's identity was a mystery, and the possibility of the portrait being of Shakespeare remained.[4]

In a 1940 article published in Scientific American, Charles Wisner Barrell shifted the identity of the sitter to Edward de Vere, the seventeenth Earl of Oxford (1550-1604). After examining the portrait with X-rays, Barrell found that the forehead, ruff, and inscription had been altered, and discovered a coat of arms beneath the inscription. Barrell interpreted these changes, especially the obscured coat of arms, as proof that the portrait was Edward de Vere. Barrell attributed the portrait to Dutch painter Cornelius Ketel (1548-1616), also based on information unearthed by his X-rays – this time an inscription of the initials "C.K."[5] This speculation continued in Charlton and Dorothy Ogburn's This Star of England, which connected the portrait to Hamlet and King Lear, again based on the presence of the skull.[6]

The case was settled in 1979, when the portrait was restored in preparation for exhibition. Uncovered during this session was the elusive coat of arms, which firmly identified the sitter as Sir Hugh Hamersley, a merchant who served in a variety of roles in the City of London, among them Lord Mayor and Master of the Haberdasher's Club.[7] The last legible letters on the coat of arms spell "MORE," the last four letters of Hamersley's motto, "HONORE ET AMORE."

Lawsuit

Meredith Underhill, a descendant of a Stratford-upon-Avon family contemporary with Shakespeare's, contacted Folger Shakespeare Library curator of books and manuscripts Giles E. Dawson in 1947 about the authorship question of Shakespeare. Dawson's response included a dismissal of C.W. Barrell's examination of the Ashbourne portrait as fraudulent. The letter resurfaced in 1948 at a meeting of the Shakespeare Fellowship in New York, when Underhill was prevented from speaking in favor of Shakespeare's authorship. Represented by Charlton Ogburn,[8] Barrell subsequently sued Dawson for libel for $50,000. Barrell was never able to produce the photographs and other pieces of evidence cited in his Scientific American article. After reaching the Washington, D.C. District Court, the suit was dropped in November 1950.

Provenance

The portrait's earliest known owner was the Reverend Clement Usill Kingston, who purchased it in London in 1847. Later that year, it was sold to a Mr. Harvard; after Harvard's death, it was acquired by R. Levine before 1910. In 1928, it was sold at auction to Eustace Conway. Conway put it up for auction the next year, but purchased it back before selling it to Emily Jordan Folger in 1931 for $3,500.

Notes

<references>

- ↑ William L. Pressly, "The Ashbourne Portrait of Shakespeare: Through the Looking Glass," Shakespeare Quarterly 44 (1993): 68.

- ↑ William L. Pressly, A catalogue of paintings in the Folger Shakespeare Library : "as imagination bodies forth" (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 300.

- ↑ Pressly 58-59.

- ↑ Pressly 59-60.

- ↑ Pressly 61.

- ↑ Pressly 64.

- ↑ Pressly 64-66.

- ↑ Pressly 62-63.