Manifold Greatness: The Creation and Afterlife of the King James Bible

Manifold Greatness: The Creation and Afterlife of the King James Bible, one of the Exhibitions at the Folger, opened on September 23, 2011 and closed on January 16, 2012. The exhibition is at the center of an ambitious project partnering the Folger Shakespeare Library and the Bodleian Library of the University of Oxford, which recently produced a related exhibition, Manifold Greatness: Oxford and the Making of the King James Bible. After the Folger exhibition closed in January 2012, it traveled to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin, which assisted in the production of the website (now archived).

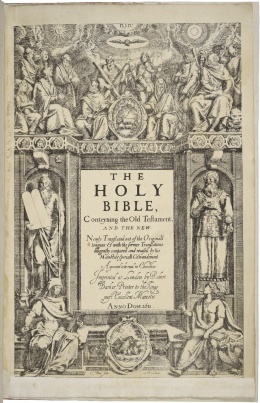

Through materials from the year 1000 to 2011, Manifold Greatness: The Creation and Afterlife of the King James Bible offers a "biography" of one of the world's most famous books, the King James Bible of 1611, which marks its 400th anniversary in 2011.

Beginning with tenth-century Anglo-Saxon biblical poems, the exhibition moves swiftly to the dramatic story of the early English Bibles, for which translators sometimes risked and even lost their lives. Rare books, manuscripts, and portraits then tell the stories of the tense conference at which James I agreed to a new Bible, and the four dozen or more top English scholars who created it over several years.

A look at the centuries-long "afterlife" of their famous text in public life, literature, entertainment, and the arts takes up the second half of the display—including, among numerous other items, the Folger first edition of the King James Bible, seventeenth-century family Bibles and lavishly bound editions, Handel's Messiah (based largely on the King James Bible), King James Bibles owned by Frederick Douglass and Elvis Presley, and the voices of the Apollo 8 astronauts as they read verses from Genesis on Christmas Eve 1968 as they orbited the Moon.

Curation

This exhibition was co-curated by Hannibal Hamlin and Steven K. Galbraith.

Hannibal Hamlin, Associate Professor of English at The Ohio State University, studied English at the University of Toronto and completed his doctorate in Renaissance Studies at Yale University. Renaissance literature and culture, especially Shakespeare, Donne, the Sidneys, and Milton, the Bible as/and/in literature, metrical psalms, and lyric poetry are among his scholarly interests.

His publications include Psalm Culture and Early Modern English Literature (Cambridge, 2004), The Sidney Psalter: Psalms of Philip and Mary Sidney, co-editor (Oxford World Classics, 2009), The King James Bible after 400 Years: Literary, Linguistic and Cultural Influences, co-editor (Cambridge, 2011), along with numerous journal articles, book chapters, and reviews.

A book on the Bible in Shakespeare is Hamlin’s major current project, in support of which he has been awarded fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American Council of Learned Societies (a Frederick Burkhardt Fellowship), and the National Humanities Center, among other grants.

He is editor of the journal Reformation and guest editor of a forthcoming forum on Poetry and Devotion for Religion and Literature. To mark the 400th anniversary of the King James Bible he is also organized an international scholarly conference at OSU in May 2011.

Steven Galbraith is the former Folger Shakespeare Library’s Andrew W. Mellon Curator of Rare Books (2008–2011) and is now Curator of the Cary Graphic Arts Collection at Rochester Institute of Technology, is an expert on the history of the book. He came to the Folger in 2007 from the Ohio State University Library, where he was Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts as well as a Visiting Professor of English. Prior to this he worked as a reference librarian at the University of Maine.

His publications include The Undergraduate's Companion to English Renaissance Writers and Their Web Sites (Libraries Unlimited, 2004) and articles in Reformation and Spenser Studies.

He is currently working on a critical edition of Thomas Drue’s Duchess of Suffolk, a book on Edmund Spenser’s printing history, and a textbook on rare book librarianship.

He earned his MLS from the University of Buffalo and his PhD in English Renaissance Literature from the Ohio State University.

Curators' insights

On the exhibition's opening day, September 23, 2011, the Folger interviewed the curators to get their insights into the exhibition and what they hope visitors will take away from it.

Steve Galbraith: I'd like to humanize the story for visitors. These were real people making great sacrifices—William Tyndale, an earlier Bible translator, lost his life—and it also took hard labor to produce translations. We focus, for example, on John Rainolds, who worked on the King James Bible literally on his deathbed. Then you turn the corner and come to the cultural influence of the King James Bible, and that's all about people, too—the authors, the musicians. It was a challenge to represent that, though, with items from this whole universe of examples.

Hannibal Hamlin: Yes, and how to place those examples within the cases became a question for us, too. We found ourselves putting an image of Martin Luther King, Jr., and a still of Linus from A Charlie Brown Christmas in the same case, as well as a rare Folger copy of Handel's Messiah. They're all part of this larger story of the influence of the King James Bible.

Steve Galbraith: Manifold Greatness is also the first project to bring together what our Oxford colleague Helen Moore calls the "Big Three," the three major surviving manuscript records of the translation of the King James Bible.

Hannibal Hamlin: The Big Three! That's the Epistles translation from the Lambeth Palace Library; the translator John Bois's notes (or rather, a very old copy of his notes) of some of the translators' discussions; and an annotated copy of a Bishops' Bible showing the translators' changes from that text.

Steve Galbraith: The Bishops' Bible, with words crossed out and changes made—that really shows you, word by word, the painstaking process of translation that created the King James Bible, and how it all came out of the deep education and training of those translators.

Hannibal Hamlin: The idea of a King James Bible exhibition at the Folger snowballed as we began to work with the Bodleian Library at Oxford and later with the American Library Association on the traveling panel exhibit, and when we applied for the NEH grant. As the project developed, we could see the Folger exhibition would be framed differently, that it would have a longer, broader scope, including America as well as England, and coming up to the present.

Steve Galbraith: That meant we would need to borrow some materials for the later period, in addition to the earlier items that include our own rare Folger holdings. But with the prospect of the traveling panel exhibit, it was exciting to be able to share our Folger expertise and interpretation of the subject so widely. It really struck home to me today when we met with the coordinators from the 40 libraries around the United States that will be showing the traveling panel exhibit. They were just so enthusiastic; they have so many plans for the presentations where they are. I was really overwhelmed that our work in the Folger exhibition here is going to travel to that many places and people.

Hannibal Hamlin: Part of our partnership with the Bodleian included their loans of some very early materials, too. The Anglo-Saxon manuscript from about the year 1000, the Wycliffite Bible manuscript from the 1380s—I always gravitate toward those in the first case as I walk in.

Steve Galbraith: We wanted to include a nineteenth-century American family Bible and we hadn't found the right one. Then, rather hesitantly, Hannibal mentioned his own family Bible, and (Folger exhibitions manager) Caryn Lazzuri and I loved it.

Hannibal Hamlin: It feels odd, but nice, that my family Bible is in the exhibition. I've been surprised at how interested people are in that—a family Bible of one of the curators. And there's a Capitol Hill connection; my great-great-great-grandfather was Abraham Lincoln's first vice president. We're showing the page with the record of his two marriages. People in the family had looked at the front and the back pages of the Bible before and not seen much of interest. But from working on this exhibition, I knew that there are often records in the middle, between the two Testaments. And that's what I found. I was really happy to see that this existed.

Contents of the exhibition

Manifold Greatness exhibition material

This article offers a comprehensive and descriptive list of each piece included in the exhibition.

Image Gallery

To view highlighted images from this exhibition, visit this Flickr photo album.

Scholars' insights on Manifold Greatness

William Tyndale (case 1, item 1)

Steve Galbraith, co-curator of the Manifold Greatness exhibition, on Tyndale Fragments.

One of the most important people in the story of King James Bible is William Tyndale who lived and died almost a century before the King James Bible was printed. In his day, William Tyndale translated much of the Bible into English, though it was heresy to do so. Rather than risk his life in England, he fled to Continental Europe to work on an English translation of the Bible and spent most of the later part of his life on the run. The first fruits of his labors, an English translation of the New Testament, were printed in Worms, Germany in 1526. In 1530, he printed an English translation of the Pentateuch or the five books of Moses. Because Tyndale’s translations were banned in England they were smuggled into the country. Many copies were destroyed, thus very few survive. These leaves from Tyndale’s Pentateuch were found inside the boards or covers of another unrelated book, suggesting they ended up as scrap paper in a bookbinder’s shop. While Tyndale never did finish a complete English translation of the Bible, his work was a major influence on most 16th and 17th century English Bibles, including the King James Bible.

Listen to Galbraith discuss Tyndall's work.

Dueling Notes (vitrine 1, items 1 & 2)

Hannibal Hamlin on dueling marginal notes in the Geneva and Rheims Bibles.

A full-scale battle of biblical interpretation takes place in the margins of two sixteenth-century Bible translations. The Geneva Bible was famous for its copious marginal notes, guiding the reader with alternative translations, cross-references to other relevant passages, and interpretations. It was really the first English Study Bible. Most of the notes were uncontroversial, but a few reflect the radical Calvinism of the translators. The Book of Revelation, for instance, was often interpreted by Protestants as a prophecy of the evils of the Catholic Church. This was made easier by the coincidence that the “Rome” condemned in Revelation (the Roman Empire of the first century) was the same city as the later “Rome” of the Pope and the Vatican. So the beast with seven heads signified the seven hills of Rome, whether in the first century or the sixteenth. Given the harshly anti-Catholic notes in the Geneva Bible, it’s not surprising that when English Catholics published their own Bible, their interpretive notes fired back against the Protestants. The marginal notes debating the identity of the Whore of Babylon in the Geneva Bible and the Rheims Bible are in sharp argument with each other.

Hear about this Biblical debate.

Elizabeth I’s Bishops Bible (case 3, item 1)

Steve Galbraith on one of the Folger Library's greatest treasures.

In a letter dated September 12, 1568, Archbishop Matthew Parker asks Queen Elizabeth's chief advisor William Cecil, Lord Burghley to present to Queen Elizabeth I “a specially-bound copy” of the English Bible that he and his Bishops had just completed. The Bible bound in scarlet velvet is likely that Bible. If you look closely at the silver diamond in the middle, you will see Elizabeth’s royal arms and the initials “EL” and “RE” for “Elizabetha Regina, Latin for “Queen Elizabeth.” Also look for the Tudor roses found on each of the silver bosses. Because this Bible was likely owned by Queen Elizabeth I, it is truly one of the Folger Library’s greatest treasures. This translation of the Bible, known as the Bishops’ Bible, is also of great importance to the King James Bible, because each translator working on King James Bible was given a 1602 edition of the Bishops Bible to use as their copy text.

Hear about Elizabeth's Bishops Bible.

John Rainolds (above case 5)

Steve Galbraith on John Rainolds

John Rainolds is a central figure in the creation of the King James Bible. President of Corpus Christi College, Oxford and a leader of the Puritan movement in England, Rainolds was one of those advocating for religious reforms at the Hampton Court Conference. It was Rainolds who in the closing minutes of the second day of the conference proposed to King James the idea of a new English translation of the Bible. Although his health began to fail, in the years that followed he worked unfailingly with the First Oxford company on the translation of the Old Testament prophets. Weekly meetings were held in his Corpus Christi lodgings and it is said that when his health severely weakened his colleagues would carry Rainolds from his bed to the meeting room. He died on May 21, 1607. Although he did not live to see the publication of the King James Bible in 1611, Rainold’s legacy as a religious leader and Bible translator continues to be celebrated, particularly in the anniversary year of the Bible translation that he initiated.

Listen to Galbraith discuss the important role Rainolds played in the creation of the King James Bible.

Translating the Bible to English (vitrine after case 5)

Hannibal Hamlin on the Annotated Bishops Bible

The annotated copy of the Bishops Bible in front of you is one of only three original documents that survive from the translation process of the King James Bible. Manifold Greatness is the first exhibition ever to bring all three together in one place. Every translator was given an unbound copy of the Bishops’ Bible to use as their base text. Even though the Geneva Bible was more popular, the Bishops’ Bible was the official translation of the Church of England from 1568 until 1611. The copy you see here is the only one of the four dozen to survive, though it may consist of parts of several. Since the original copies were unbound, pages from different copies may have gotten mixed together. One of the original translators recorded the decisions of his company directly on the page, crossing some words out, inserting others. It may seem surprising that so few records of the translation process survive, but the translators probably never thought their Bible would last so long or become such a cultural icon. They certainly wouldn’t have thought anyone would be interested in their labors, just in the product of it, the Bible itself.

Listen to Hamlin discuss the translation process.

The Wicked Bible (case 7, item 2)

Steve Galbraith on one of the most notorious printing errors

To err is human, and printing in the seventeenth century was a very human process that often produced very human mistakes. Most were simple misprints that most readers would overlook. But when a misprint catches the eye of the King himself, you know you’ve severely erred. Such was the case with the so-called “Wicked Bible” of 1631. This edition of the King James Bible contains the infamous misprint, “Thou shalt commit adultery.” The mistake of omitting one small word is a relatively simple one to make, though, in this case, the result was wicked enough to earn the printers Robert Parker and Martin Lucas a 300 pound fine, a pretty major sum for the time. This manuscript court document from the Acts of High Commission shows King Charles I showing some forgiveness by remitting the fine in exchange for Barker and Lucas printing Greek texts being translated by the King’s librarian, Patrick Young. Thus the printers survived to print another day, though I imagine their compositors took greater care in setting type.

Hear about printing mishaps.

Sir Justinian Isham (case 8, item 2)

Steve Galbraith on the Isham Bible

I must admit that this book is my favorite in the exhibition. Books have stories to tell beyond the texts they contain. This pocket-sized copy of the third part of the Bible is a perfect example. A manuscript note in the front of the book reads “This was ye [the] only booke I carried in my pockett when I travelld beyond ye [the] seas ye [the] 22d year of my Age; & many years after.” The inscription is signed, “Just. Isha[m].” While many book owners from the early modern period inscribed their names into their books and perhaps even supplied a date, very few provided such personal details. “Just. Isha[m]” is Sir Justinian Isham, who lived from 1611 to 1675. As the inscription suggests, in 1633 he travelled to the Netherlands at the age of twenty-two.

Hear about a pocket-sized copy of the Bible.

The Psalm 46 myth (case 10, item 1)

Hannibal Hamlin on Shakespeare's connection to the KJV

Some time around the turn of the twentieth century, someone with codes on the brain and too much spare time discovered that Psalm 46 in the King James Bible contained the secret “signature” of Shakespeare. The myth that Shakespeare was involved in translating the King James Bible lingers on but is only a myth. There is no real evidence for it, just the imaginative “code” breaking, and it makes no sense historically. It probably grows out of a couple of cultural beliefs that have been widespread since the nineteenth century. The first is that the King James Bible is the greatest achievement of English prose writing. The second is that Shakespeare is the greatest writer in English literature. From these assumptions grew the idea that, as England’s greatest writer, Shakespeare must have been consulted in the creation of the great writing of the King James Bible. This is misguided. The translators of the King James Bible were not at all concerned with literary style, just with making their translation as literally accurate as possible. Whatever style the translation has is an accidental by-product. Furthermore, all but one of the translators were clergymen, and all of them were exceptionally knowledgeable about ancient languages. Shakespeare had no place among them, and they would have found the idea of consulting him ridiculous, if they’d even heard of him at all.

Hear about the mis-connection between Shakespeare and the King James Bible.

Frederick Douglass (case 11)

Hannibal Hamlin on the Douglass Bible

This is a King James Bible owned by the freed slave and abolitionist statesman Frederick Douglass. As Abraham Lincoln observed, the King James Bible was carried into battle by both North and South in the American Civil War. Books like Josiah Priest’s Bible Defence of Slavery argued that slavery was instituted by God’s curse on Noah’s son Ham, and was practiced throughout the Old Testament. Slave owners read to their slaves Paul’s Epistle to the Ephesians 6:5, “Slaves be obedient to them that are your masters according to the flesh, with fear and trembling, in singleness of your heart, as unto Christ.” Abolitionists, on the other hand, cited Paul in Galatians: “there is neither bond nor free . . . for ye are all one in Christ Jesus.” And African Americans quickly made the Bible their own, seeing in the Exodus of Israel out of Egypt the promise of their own emancipation. Frederick Douglass distinguished between the “Slaveholding Religion” and the “Christianity of Christ,” and countered the arguments about Ham by pointing out that many slaves were descended from white owners as well as other slaves.

Listen to Hamlin discuss the importance of the KJV for African Americans during the American Civil War.

Moby-Dick (case 12, item 4)

Hannibal Hamlin on the literary influence of the King James Bible

Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, which you see here in an edition illustrated by Rockwell Kent, is one of countless novels, plays, and poems in English influenced by the King James Bible. This influence is most obvious in the titles of novels like William Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses, Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, and Henry James’s The Golden Bowl. But other literary works borrow characters, plots, themes, and even the language of the King James Bible. Moby-Dick is Melville’s dark struggle with the traditional Christian God and the values he represents. In the Old Testament, when Job challenged God to justify his innocent suffering, God replied with a series of questions that showed Job he was unworthy to ask his question. “Canst thou draw out Leviathan with a hook?” God asked. On a symbolic level, Captain Ahab, named after the wicked Old Testament king, aims to set Job’s God straight, drawing out one Leviathan––the white whale Moby Dick––with a harpoon. Melville’s novel is full of biblical allusions, especially to the Book of Jonah, the story of the reluctant prophet swallowed by a great fish. The illustration open here is of Father Mapple preaching a sermon on Jonah in the whaler’s chapel in Nantuckett.

Listen to Hamlin discuss the connection between the King James Bible and Moby Dick.

Handel’s Messiah (case 13, item 1)

Steve Galbraith on the King James Bible's influence on music

From hymns and African American Spirituals, to Pete Seeger’s “Turn Turn Turn” to Bob Marley’s “Rastaman Chant,” the King James Bible has had profound influence on music. One of the most famous works inspired by the King James Bible is Handel’s Messiah, which takes most of its libretto directly from the translation of the book of revelation found in the King James Bible. The clip you are about to hear is the Messiah’s “Hallelujah” chorus performed in 1991 by the Choir of Oxford’s Magdalen College and the Folger Consort, a collaboration that nicely mirrors the exhibition collaboration between the Folger and Oxford.

Chorus:

- Hallelujah, for the Lord God Omnipotent reigneth.

- The Kingdom of this World is become the Kingdom of our Lord and of his Christ;

- and he shall reign for ever and ever, King of Kings, and Lord of Lords.

- Hallelujah.

- Adapted from the King James Bible: Revelation 19:6, Revelation 11:15, and Revelation 19:16

Hear the King James Bible in Handel's Messiah.

A live audio recording of selections from Handel's Messiah by the Folger Consort and the Choir of Magdalen College, Oxford is also available for free download at CD Baby.

Additional scholarship

Various scholars around the country contributed their knowledge to events held at locations for the traveling exhibition. A selection of videos from those lectures are listed below. For additional videos, watch the videos on this page or visit the Manifold Greatness YouTube page.

Lectures from the traveling exhibition

- The Making of the King James Bible, Helen Moore, editor of Manifold Greatness: The Making of the King James Bible and Fellow and Tutor in English at Corpus Christi College, University of Oxford, spoke at the Harry Ransom Center of The University of Texas at Austin, April 26, 2012

- Hebrew Idioms, Dr. Norman Jones at The University of Mississippi, June 4, 2012

- From Ancient Texts to Literary Masterpiece, Wilburn Stancil at Kansas City Public Library, July 24, 2012

- The Connection Between the King James Bible and Modern Rap Music, Dr. Valinda Littlefield at Sumter County Library, July 30, 2012

- Why Moses is Portrayed with Horns, Dr. Cyndia Clegg, Distinguished Professor of English at Pepperdine University, at Pepperdine, August 30th, 2012

- The Role the King James Bible Played in Mormonism and the Settlement of the West, Philip L. Barlow, Arrington Chair of Mormon History and Culture, Utah State University, at the University of Wyoming Coe Library, October 15, 2012

- Seventeenth-Century Needleworkers and the King James Bible Susan Frye, UW Department of English professor, at the University of Wyoming, October 22, 2012

- What Kind of a Text is the King James Bible?, Bart Ehrman at Loyola Marymount University, January 24, 2013

Manifold Greatness children's exhibition

Manifold Greatness family guide

Make it! Videos

Explore these videos to learn how to make ink, quill pens, quartos, and ruffs, 1611 style.

Manifold Greatness website

An extensive website, Manifold Greatness: The creation and afterlife of the King James Bible (now archived), jointly produced by the Folger Shakespeare Library and the Bodleian Library with assistance from the Harry Ransom Center, was created as both a lasting online resource and a companion project. It includes a variety of supplemental materials and interactive elements.[1]

Before the King James Bible

Making the book

Later influences

Additional elements

Discover answers to Frequently Asked Questions about the King James Bible or learn what separates myth from reality.

A companion blog, which follows the exhibition from March 2011 to the final traveling tour destination, provides insight into the events, artifacts, and people involved in Manifold Greatness.

Social media

Supplemental materials

Audio

The Apollo 8 astronauts

On Christmas Eve, 1968, the three Apollo 8 astronauts read aloud from the creation account in Genesis, using the King James Bible text, while in orbit around the Moon. Apollo 8 included the first lunar orbits, which meant that the astronauts were completely out of touch with Earth for 45 minutes every time their craft passed behind the Moon. By the time of the Genesis reading, the crew had circled the Moon nine times and had one more revolution to complete. A global audience estimated at half a billion heard and watched their live television broadcast, making it the most-watched broadcast in history at that time.

Lunar Module Pilot William Anders:

- We are now approaching lunar sunrise, and for all the people back on Earth, the crew of Apollo 8 has a message that we would like to send to you.

- "In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, ‘Let there be light’: and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness."

Command Module Pilot James Lovell:

- "And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day. And God said, ‘Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.’ And God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament: and it was so. And God called the firmament Heaven. And the evening and the morning were the second day."

Commander Frank Borman:

- "And God said, ‘Let the waters under the heavens be gathered together into one place, and let the dry land appear’: and it was so. And God called the dry land Earth, and the gathering together of the waters called he Seas: and God saw that it was good."

- And from the crew of Apollo 8, we close with good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas, and God bless all of you—all of you on the good Earth.

Listen to a recording of their reading.

Video

The Manifold Greatness project marks the 400th anniversary of the 1611 King James Bible. Learn about this exciting exhibition and partnership between the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford; the Folger Shakespeare Library; and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin.

Earlier English Bible translations not only led the way to the King James Bible, they also contributed to it. Manifold Greatness curator Steven Galbraith shares the stories of earlier translators, including John Wyclif and William Tyndale who risked their lives translating the Bible into English.

How was the King James Bible created? What English Bibles came before it, and what has happened since its publication in 1611? How can we begin to assess its wide-ranging cultural influence in the four centuries that followed? Curators of the Manifold Greatness exhibitions at the Folger Shakespeare Library and the Bodleian Library at Oxford explore these and other questions in this video, called Setting the stage.

As the English crown passed to rulers of different faiths, how did the kings and queens from Henry VIII to James I shape the history of Bible translation? In this video called The Crown and the Bible, curators of the Manifold Greatness exhibitions at the Folger Shakespeare Library and the Bodleian Library at Oxford, as well as other specialists, consider these and other questions.

How did the King James Bible translators go about their challenging task in the years from 1604, when King James agreed to a new English Bible, to 1611, when the King James Bible was first printed? What do we know about the day-to-day work of translation, and what special insights does it offer us into the translators' world? Watch this video, Reconstructing the process to find out.

Printing the King James Bible was a major assignment—and an expensive one—for the king's printer, Robert Barker. Learn more in this video called, Printing the book.

Watch as co-cuator Steve Galbraith demonstrates the process of printing using a model printing press at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

Co-curators Hannibal Hamlin and Steve Galbraith share some of the more well-known printing errors from early editions of the King James Bible, including the accidental substitution of Judas for Jesus (in the "Judas Bible"), the omission of an important word from the seventh commandment on adultery, and even some gender confusion in the 1611 edition.

Co-curator Hannibal Hamlin talks about perhaps the most enduring influence of the King James Bible: its language, which has inspired poems, novels, and other writings spanning four centuries and every English-speaking literary tradition.

In this video called, One book, many forms, the curators of the Manifold Greatness exhibition explore the history of the physical form of the King James Bible—including the growing popularity of illustrated editions over the centuries and the role of the King James Bible in today's digital media.

Related publications

Manifold Greatness: The Making of the King James Bible (2011), published by Bodleian Library Publishing, is a richly illustrated, accessible, and meticulous account of the creation and afterlife of the 1611 King James Bible. Edited by Helen Moore and Julian Reid, contributors include Moore and Reid, Valentine Cunningham, Steven Galbraith, Hannibal Hamlin, Diarmaid MacCulloch, Peter McCullough, Judith Maltby, Christopher Rowland, and Elizabeth Solopova.

Related programs

Talks and Screenings at the Folger

- KJV in the USA: The King’s Bible in a Country without a King, Jill Lepore, September 29, 2011

- Robert Pinsky, Reading for the O.B. Hardison Poetry Series, October 4, 2011

- Poetics and the Bible, December 16, 2011

Folger Theatre

- Othello, October 18 – December 14, 2011

Folger Consort

- Early Music Seminar, A New Song: Celebrating the 400th Anniversary of the King James Bible, Wednesday, September 28, 2011

- A New Song: Celebrating the 400th Anniversary of the King James Bible, September 30 – October 2, 2011. Recording available through CD Baby

- Selections From Handel's Messiah: Recorded Live December 20-23, 1993, available for free download through CD Baby.

Conferences

- The King James Bible and Its Cultural Afterlife, The Ohio State University, May 5–7, 2011

- Anglo-American History of the KJV, Folger Institute, September 29 – October 1, 2011

Traveling exhibition

A traveling panel exhibition, inspired by the Folger exhibition and produced by the Folger in partnership with the American Library Association (ALA) toured 40 sites throughout the United States from 2011 through the summer of 2013.

- Read blog posts about the various tour locations.

- Watch videos from host sites for the traveling exhibition including lectures by experts, events, exhibits, and more.

- View a Flickr photostream of images from events and exhibitions from various tour locations.

Suggestions for further reading and research

This bibliography is not meant to be comprehensive, but is meant to lead the interested reader to some of the many resources on the King James Bible.

The following finding aids were prepared by the Folger Shakespeare Library and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin, to suggest some of the rare resources at those institutions which relate to the topics included in the Manifold Greatness project. Hands-on research access to rare materials is limited. Scholars and other qualified researchers seeking the opportunity to work with these or other rare books and manuscripts should apply to the library in question.

The King James Bible has such an extensive religious and cultural history that there are almost countless websites that could be listed; this link offers some useful starting points.

This exhibition was made possible by a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this exhibition do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

- ↑ The exhibition website was amongst the winners of the 2012 Leab Exhibition Awards from the RBMS (Rare Books and Manuscripts Section) of the ALA (American Library Association). The Awards recognize outstanding exhibition catalogs issued by American or Canadian institutions in conjunction with library exhibitions, as well as electronic exhibition catalogs of outstanding merit issued within the digital/Web environment.