Inter-Faith Encounters: English Protestants and the Hebrew Bible

This essay was composed for the NEH Summer Institute: Shakespeare from the Globe to the Global (seminar).

Sara Coodin, University of Oklahoma

Renaissance English culture was markedly preoccupied with the Hebrew language and the Hebrew Bible, and by implication, also with Jews. That preoccupation came to the fore in Tudor England with Henry VIII’s desire to furnish Scriptural grounds for his divorce. The Latin Bible failed to supply those grounds, but Henry hoped to locate a Scriptural precedent in either the original Hebrew text of the Bible or its Judaic exegesis. The cultural interest in Hebrew in England expanded in the decades after Henry’s reign with the influx and popularization of humanist learning, which advanced a program of textual scholarship that prioritized the discovery, translation, and study of original texts.

Despite a growing interest in the original text of the Bible and the Hebrew language in this period, sixteenth-century-English Protestants did not have the necessary skills to delve into Hebrew texts. The desire to consult with original materials and, in some cases, with rabbinic and Talmudic commentary on difficult passages often necessitated face-to-face encounters with rabbis or recent converts who were fluent in Hebrew and familiar with the Judaic exegetical tradition. These kinds of inter-faith encounters took place largely in Continental Europe in the sixteenth century. However, there are also extensive signs of textual encounters between Protestants and Jews in England, evidenced in English-language Bible commentaries from the period, where English Protestant theologians such as Andrew Willet directly address rabbinic commentary in their work.

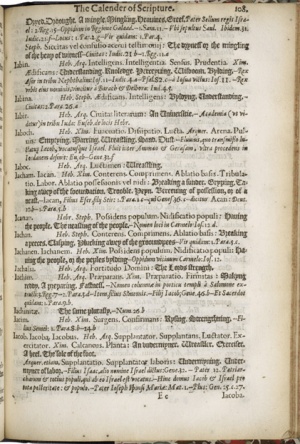

In the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, many printed English Bible translations and commentaries prominently advertised having consulted with the Hebrew text. “Consultation with the Hebrew” was a marker of quality, and a badge signaling a well produced, authoritative, and newly revised text. A variety of Biblical materials incorporated this claim on their title pages, including the 1575 Calendar of Scripture, which catalogues etymologies of Scriptural names and their Hebrew meanings. In this page from the Folger Shakespeare Library’s edition of The Calendar of Scripture, Jacob’s name is correctly explained through its Hebrew etymology. In Hebrew, Ya-akov (Jacob) means “heel-grabber,” which is interpreted figuratively as “usurper.”

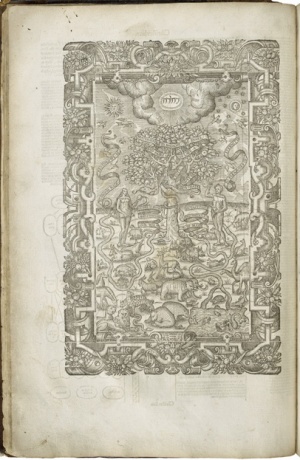

In early seventeenth-century English Bibles, characters from the Hebrew Bible figure prominently alongside those from the New Testament, and Hebrew is accorded a prominent visual place in frontispieces and illustrations. In this 1602 Bishops' Bible, the ten tribes of Israel flank the left-hand side of the frontispiece, while the right-hand side features apostles. The very top and center of the page showcases a Hebrew word encased in rays of light containing the letters yud, heh, vav, heh, which spell out Yehovah, the sacred Hebrew word for God.

The late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries in England were characterized by a zeal for translating the Bible into English — a zeal that, in many ways, culminates in the production and publication of the 1611 King James Bible. However, the widespread interest in translating the Bible in consultation with the original text raises a series of suggestive questions about the relationship between Protestant Englishmen and the Jewish materials they were consulting. Just what were Protestant theologians seeing when they pored over Hebraic materials? How much did English theologians see past in the interest of framing those materials within a Protestant schema? Many scholars have emphasized the ways in which early modern theologians read Jewish sacred writings and Jews through a Patristic dichotomy that de-legitimized their Jewish aspects, casting the Hebrew Bible as the “Old” Testament — a debased, primitive form of worship. However, English writers also often described Jews and Judaism as intransigent, highly resistant to any and all attempts at assimilation, and therefore impossible to either Christianize or eradicate. In short, Jews were often represented as a force to be contended with, and one that stubbornly resisted attempts at Christian assimilation.

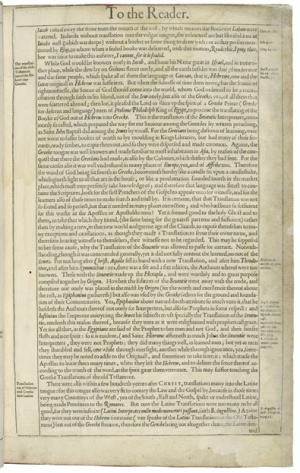

Early modern English culture’s ongoing fascination with Hebrew and use of Hebraic materials to compile new translations of the Bible suggests increasing awareness of a parallel tradition among Jews that approaches and explicates Biblical narratives and figures very differently from how Protestants were figuring them. In this introductory note to readers in the Folger’s copy of the1611 King James Bible, translators make reference to Jacob — a figure from the Hebrew Bible — as a way of explicating the act of translation itself. “Translation,” they write, “removeth the cover of the well, that we may come by the water, even as Jacob rolled away the stone from the mouth of the well, by which means the flocks of Laban were watered.” Although the translators’ message is clearly a Protestant one in which translators make Scripture available to a wide audience, the figure chosen to represent this image is one from the Hebrew Bible. Which Jacob is being referenced here? The Judaic Jacob, or the Patristically reinterpreted, Protestantized one?

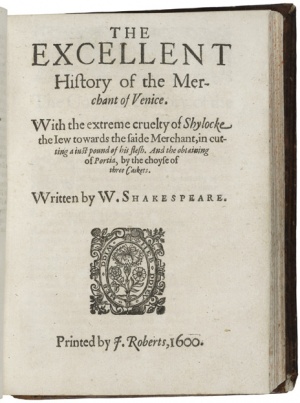

In Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice, Shylock cites an episode from the Hebrew Bible featuring Jacob successfully breeding his uncle’s parti-colored lambs. Shylock cites a passage from Genesis in a way that may suggest a different perspective on these verses from the one that Antonio provides. In this 1600 edition of The Merchant of Venice from the Folger’s collections, Shylock not only identifies with Jacob; he identifies himself as Jacob. In this text of the play, he pronounces:

- When Jacob, graz’d his Unckle Labans sheepe,

This Jacob from our holy Abram was

(As his wise Mother wrought in his behalf)

The third possessor; I, he was the third.

Later versions of the play change the ‘I’ to ‘aye,’ suggesting at a less proprietary relationship between Shylock and his Biblical forefather. But we might just as easily read the line as Shylock emphasizing how he (as Jacob) was the third possessor of that dynastic wealth. As the third possessor, his wealth functions as a token of God’s covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Shylock may very well be asserting his membership in the Jewish or Hebrew nation in this episode.

Antonio’s response to Shylock’s use of Scripture is quick and dismissive. He accuses Shylock of appropriating Christian Scripture illegitimately: “The devil can cite Scripture for his purpose.” However, Antonio’s comment signals a problem with which Shakespeare’s contemporaries were well familiar. What Christians label the “Old” Testament in fact encompasses an anterior tradition’s sacred writings: the Jewish Torah. In a strict chronological sense, Christians are the appropriators of Jewish sacred writings, and they occasionally required the assistance of Jews to successfully translate and interpret those writings. Early modern England’s growing awareness, appreciation, and reliance on the Hebrew Bible and the Hebrew language would appear to signal a recognition of that anterior tradition. The cultural awareness and fascination with Hebrew in Renaissance England repeatedly and, at times, very deliberately recalls the presence — theological, linguistic — of that anterior tradition, and of Jews.

Suggested Reading

Coudert, Alison, and Jeffrey Shoulson, eds. Hebraica Veritas? Christian Hebraists and the Study of Judaism in Early Modern Europe. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

Friedman, Jerome. The Most Ancient Testimony: Sixteenth-Century Christian-Hebraica in the Age of Nostalgia. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1983.

Jones, G. Lloyd. The Discovery of Hebrew in Tudor England: A Third Language. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1993.

Manuel, Frank. The Broken Staff: Judaism Through Christian Eyes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992.

Pick, B. ‘History of the Printed Editions of the Old Testament, Together With a Description of the Rabbinic and the Polyglot Bibles.’ Hebraica 9.1/2 (Oct 1892 —Jan 1893), 47–116.

Rashkow, Ilona. ‘Hebrew Bible Translation and the Fear of Judaization.’ The Sixteenth Century Journal 21.2 (Summer 1990): 217–33.

Willet, Andrew. Hexapla in Genesin. London, 1608.