History in the Making: How Early Modern Britain Reimagined its Past

History in the Making: How Early Modern Britain Reimagined its Past, one of the Exhibitions at the Folger opened January 24, 2008 and closed on May 17, 2008. The exhibition was co-curated by Alan Stewart and Garrett Sullivan with senior cataloger Ron Bogdan as consultant.

Early modern Britain faced a problem: how to reconcile its present with a past visibly at odds with it. Facing the dynastic and religious upheavals caused by the Wars of the Roses, the rise of the Tudors, and the Protestant Reformation, the British tried to account for their present by rethinking and rewriting their history. This exhibit considers the ways in which the early modern British made—and remade—their own history, focusing both on how key events—such as the controversial execution of Mary Queen of Scots or the murderous Gunpowder Plot—were interpreted in the period, and on crucial ideas that helped to shape those interpretations. It also examines some of the period’s most important figures, both real (Charles I) and imaginary (Shakespeare’s Falstaff), and the roles they played in the making of British history.

Exhibition material

The Brutus Myth

In the sixteenth century, Britain had its own foundational story, the so-called "Brutus myth," which neatly linked the origins of Britain with the classical civilizations of Troy and Rome. Brutus (or Brut) was a descendant of Aeneas, who settled in Italy after the Trojan War. After being banished from Italy, as the story goes, Brutus found his way to Britain, which he named after himself and populated with his descendants. These semi-mythical ancient kings of Britain included such figures as Gorboduc, Leir, and Cymbeline, who later provided the inspiration for plays by Shakespeare and others.

Listen to curator Garrett Sullivan discuss Falstaff's connection Sir John Oldcastle.

Items included

- John Bale. A brefe chronycle concernynge the examinacyon and death of the blessed martyr of Christ syr Johan Oldecastell the lorde Cobham, collected togyther by Johan Bale. Antwerp, 1544. Call number: STC 1276 copy 1; displayed title page.

Mary Queen of Scots

Throughout her life, Mary Stuart seemed to court controversy. A Catholic ruling over a Protestant country, she was accused of murdering her second husband in league with her third, and forced off the Scottish throne. Kept under house arrest by Elizabeth, she became a magnet for Catholic sympathizers within England. Implicated in several alleged plots against Elizabeth, she was eventually executed in 1587.

This act received wildly varying interpretations by contemporaries, who painted her as either a victim-martyr or a diabolical would-be regicide. When her son became king of England in 1603, one of his first acts was to send a velvet pall to cover his mother’s tomb in Peterborough Cathedral. Ten years later, he ordered her reburied in Westminster Abbey, facing Elizabeth. "Our dearest mother," James proclaimed, should be in "the place where the kings and queens of this realm are usually interred."

Listen to curator Alan Stewart discuss how Mary turned from Queen to martyr.

Items included

- Petrus A. Merica. Maria Jacobi Scotorum Regis filia, Scotorumque nunc Regina. Engraving, ca. 1556. Call number: ART 260-946 (size S) and LUNA Digital Image.

- Maria, Queene of Scottland. Colored engraving. Call number: 7758.3 v.3 no.4 and LUNA Digital Image.

Sir Philip Sidney

Sir Philip Sidney died, at the age of just thirty-one, after being wounded in a skirmish at Zutphen in the Low Countries. At the time of his death, he was fighting with the English forces led by his uncle, the earl of Leicester, against the Spanish occupation of the Netherlands. During his lifetime, Sidney was known as a courtier and ambassador, but it was only after his death that he would reach true fame. His premature death was mourned in a huge funeral in London; and his writings, which had previously circulated only in manuscript, were published within a few years. Within a decade he had become the quintessential English poet-courtier-soldier, an image that has endured for centuries.

The Funeral: "A Martial 'Vale'"

The funeral of Sir Philip Sidney was one of the great London events of 1587. After lying in state in the Minorites church just outside the city, the procession made its way through the capital’s streets to St. Paul’s, where Sidney was buried to the sound of a double volley, to “give unto his famous life and death a martial ‘Vale’ [farewell].” Sidney’s father-in-law Sir Francis Walsingham had “spared not any cost to have this funeral well performed.’

The streets “were so thronged with people that the mourners had scarcely room to pass; the houses likewise were as full as they might be, of which great multitude there were few or none that shed not some tears as the corpse passed by them.” Every detail was preserved on a roll made up of twenty-eight plates, seven and three-quarter inches wide, and over thirty-eight feet long, scripted by Thomas Lant, and engraved by Theodor deBry. Many years later, John Aubrey remembered seeing this scroll at the age of nine, in the parlor of a Gloucester alderman named Singleton. Singleton had the large sheets of paper pasted together so that the procession “in length was, I believe, the length of theroom at least.” But John became truly fascinated when Singleton “contrived it to be turned upon two pins, that turning one of them made the figures march all in order. It did make such a strong impression on my tender phantasy,” he recalled in his last years, “that I remember it as if it were but yesterday.”

Listen to curator Alan Stewart discuss the impact of Sidney's death.

Items included

- Crispijn van de Passe. Sydney Philippus VIX ea nostra uoco Tel fut ce digne Anglois qui proche de trepas chanta ... Engraving, 17th century. Call number: ART File S569 no.7 (size M) and LUNA Digital Image.

The Great Fire

Following the Restoration of the Stuart dynasty in 1660, Britain was to face a series of catastrophes. In 1665, London was struck by the Great Plague. The following year, a huge fire swept through the capital, lasting from Sunday, September 2 to Wednesday, September 5. Over thirteen thousand houses and eighty-seven churches, including the iconic St Paul’s, fell victim to the fire, leaving seven out of eight City inhabitants homeless. Looking for a scapegoat, Londoners attacked French and Dutch immigrants; preachers suggested that London needed to look to its own sins; while optimists saw the disaster, with its relatively low death toll, as yet another sign of God’s Providence.

These two views show how the City of London looked before and after the Great Fire. The Prague-born etcher Wenceslaus Hollar is alleged to have rushed to capture these images even while the fire was still burning—and to him we owe a view of the immediate aftermath.

Items included

- Wenceslaus Hollar. A true and exact prospect of the famous citty of London from St. Marie overs steeple in Southwarke in its flourishing condition before the fire. Etching. London, 1666. Call number: MAP L85c no.1 and LUNA Digital Image.

- Samuel Rolle. Shilhavtiyah or, The burning of London in the year 1666. London: printed by R[obert]. I[bbitson]., 1667. Call number: R1876; displayed frontispiece.

The Spanish Armada

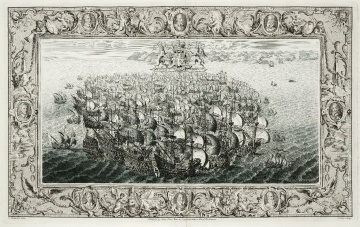

The defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 has come down through history as one of the most significant moments in British history; it has been read as providing evidence of everything from God’s defense of a Protestant nation under siege by Catholic enemies to the supercession of an old imperial power (Spain) by an emergent one. At the time, however, the defeat of the Armada was not universally seen as the decisive blow it was later taken to be, and many in England feared both future attacks from Spain and, more generally, other attempts by allies of the Catholic Church to destroy the Protestant nation.

In the House of Lords, the defeat of the Armada was commemorated by a set of ten vast hangings, commissioned around 1596 from the Dutch painter Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom (1563–1640), who specialized in marine scenes. Vroom's remarkable images, which gave various bird's-eye views of the sea-battles, hung in the Lords from 1650 until 1834, when they were destroyed in a fire. Happily, we are still able to see his work, albeit secondhand. In 1735, the engraver John Pine obtained an exclusive right to copy the tapestries, and four years later finished work on his series of engravings and Philip Morant supplied the text.

Items included

- Philip Morant. The tapestry hangings of the House of Lords: representing the several engagments between the English and Spanish fleets in the ... year MDLXXXVIII. London, [1739]. Call number: DA360 P4 Cage and LUNA Digital Image.

Providence

By the early seventeenth century, England and its monarchs had experienced a sequence of apparently miraculous escapes from danger—the series of threats on Elizabeth’s life, the Great Armada bearing down onto the English shore, the ruthless ambition of the Gunpowder Plot. It was very tempting for writers to see this apparent “deliverance” as divinely ordained for their country, and over the next century there grew the theme of Britain’s “triumph of providence” over her enemies.

The frontispiece image, from John Nalson's An impartial collection of the great affairs of state (1682), depicts Britannia fallen victim to domestic sedition and foreign threats.

Listen to curator Garrett Sullivan discuss the triumph of Providence.

Items included

- John Nalson. An impartial collection of the great affairs of state, from the beginning of the Scotch rebellion in the year MDCXXXIX. to the murther of King Charles I. London, 1682. Call number: N106 Vol. 1; displayed frontispiece.

- Triumphs of providence over Hell, France & Rome, in the defeating and discovering of the late hallish and barbarous plott, for assassinating his royall Majesty King William ye III, lively display’d in all its several branches. [London, 1696]. Call number: 244835 and LUNA Digital Image.

The Gunpowder Plot

The fifth of November was the day on which King James, his queen, peers and Parliament should have died. A group of English Catholic gentlemen, dissatisfied with the state’s treatment of Catholics, plotted to explode barrels of gunpowder under the Parliament House in Westminster, during the opening ceremony of Parliament. Betrayed by a panicked colleague the conspirators were either killed trying to escape or executed later. James proclaimed the fifth of November a public holiday—a “red letter day”—effectively inscribing this event (or non-event) into Britain’s calendar.

The near escapes from the Armada and the Gunpowder Plot allowed historians to see Britain—and especially Protestant Britain—as somehow divinely favored. A typical pamphlet on the Gunpowder Plot lauded Great Britaines great deliverance from the great danger of Popish powder, and in time writers drew up lists of nefarious plots against the sovereign and the country, all of which were foiled, and thus proved that Britain’s survival was guided by Providence.

Items included

- Samuel Ward. The Papists Powder-Treason. 1689. Call number: 251142 and LUNA Digital Image.

- William Leigh. Great Britaines, great deliuerance, from the great danger of Popish powder. London: Printed [by T. Creede], 1606. Call number: STC 15425.

A New Antiquarianism

Perhaps because of the constant writing and rewriting of the past, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw a new and passionate interest in historical research. Several gentlemen and scholars became antiquarians, intent on collecting and preserving the traces of the past in manuscripts, coins, relics or ruins. In 1586, the College of Antiquaries was formed in London. Among its numbers were such luminaries as the London historian John Stow, who wrote a celebrated Survey of London, piling up amazing detail about the capital’s buildings and history; William Camden, who had particular interests in England’s Roman legacy, producing the massive tome Britannia [1586]; William Dugdale’s interest focused on his native county of Warwickshire and produced the beautiful volume The antiquities of Warwickshire illustrated [1656]. The antiquarians provided British readers with different possibilities for their past. Were they descended not from Brutus but from the Picts, Angles, Saxons, Danes, or Normans? What was Britain’s relationship with ancient Rome? In 1612, John Speed published a history that told Britain’s story through a series of invasions: The history of Great Britaine under the conquests of the Romans, Saxons, Danes and Normans.

Among the side-effects of this new antiquarianism was the birth of Anglo-Saxon culture as an object of study. From the 1560s onwards, there was a concerted campaign to present to the world documents from England’s Anglo-Saxon period. For lawyers such as William Lambard, this was part of an attempt to find early sources for English law. Most importantly, though, it appealed to churchmen like Matthew Parker, archbishop of Canterbury, and Protestant historians such as John Foxe, who were furthering John Bale’s researches into England's church. Texts such as the Gospels in Anglo-Saxon, according to Foxe, showed that “religion presently … is no new reformation of things … but rather a reduction of the Church to the Pristine state of old conformity.”

Listen to curator Alan Stewart discuss the rise in the Anglo-Saxon history.

Items included

- Archaionomia, siue, De priscis anglorum legibus libri. London, 1568. Call number: STC 15142 copy 1; displayed B2 and opposite.

- The Gospels of the fower Euangelistes translated in the olde Saxons tyme out of Latin into the vulgare toung of the Saxons, newly collected out of auncient monumentes of the sayd Saxons, and now published for testimonie of the same. Anglo-Saxon and English in parallel columns. London: Printed by Iohn Daye, 1571. Call number: STC 2961.

Supplemental material

Explore History in the Making through this audio tour.