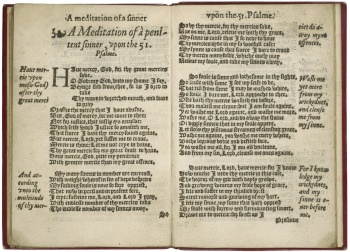

A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner STC 4450

A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner is the first English-language sonnet sequence, written by Anne Locke Prowse (c. 1530 – c.1590-1607). It was published in 1560 alongside Locke’s translations of four of John Calvin’s sermons on Isaiah 38.The twenty-six poems in the sequence gloss Psalm 51.

Author's biography

Anne Locke was born to a prosperous London merchant family around 1530. Her father, Stephen Vaughan, and mother, Margaret Gwynneth, were active at the court of Henry VIII. Her first husband, Henry Locke, was also descended from London merchants, though the Lockes were more socially prominent and more well-known for their staunch Protestantism. Through her husband, Locke was connected with John Knox, leader of the Reformation in Scotland. Knox occasionally boarded with the Lockes during sojourns in London. After Mary I's ascension to the English throne in 1553, Locke lived in exile in Geneva with other Protestants, where she became acquainted with Calvinist theology. She returned to London in the summer of 1559; around this time, she began translating Calvin's sermons into English and composing sonnets for publication in 1560. In 1571, Henry Locke died; the next year, Locke married the preacher Edward Dering. Dering, however, died in 1576. Locke married for a third and final time to cloth merchant Richard Prowse, who was also a member of Parliament.[1] During their marriage, the Prowses moved to Exter, where Prowse had establisehd himself as a draper and served three times as mayor. In Exeter, Locke established close ties to local female Protestant writers like Anne Dowriche.[2]

Despite her apparent reputation as a gentlewoman of great learning and religious merit, Locke's known body of work is small. Beyond A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner, Locke's works include a dedicatory poem written in Latin, one of many composed by a variety of authors for a multilingual, illuminated manuscript of Doctor Bartholo Sylva's Giardino cosmografico coltivato, held by the Cambridge University Library. Locke, her second husband Edward Dering, and the five Cooke sisters, all staunch Protestants, compiled the manuscript and presented it to Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester.[3] Nearly twenty years pass before Locke's writing appears again; in 1590, she translated John Taffin's Of the markes of the children of God from the French.[4] After 1590, Locke disappears from the historical record; she probably died around or before 1602, when she was praised posthumously by Richard Carew in his Survey of Cornwall.[5]

Publication history

Locke's sonnet sequence was probably written around 1559, the year of her return to London from exile in Geneva, and published in 1560, at the end of a volume that also contained her translations of four of John Calvin's sermons on Isaiah 38. Sermons of John Calvin upon the Songe that Ezechias made after he had bene sicke...Translated out of Frenche into Englishe was entered into the Stationer's Register on January 15, 1560 by John Day. A letter of dedication to the Protestant patron Katharine Bertie, duchess of Suffolk, precedes the translations and sonnets.

A modern edition of the sequence, and Locke's other works, was edited by Susan M. Felch in a 1999 volume titled The Collected Works of Anne Vaughan Lock.

Authorship

After her lifetime, Locke was not widely known as the creator of her sonnet sequence and the translations which it accompanies. Thomas Roche first ascribed this material to her in his 1989 Petrarch and the English Sonnet Sequences and is thus also the first scholar to identify her as the author of the first English sonnet sequence.[6] The typical competitor for authorship of the sequence is John Knox. Records of Knox's correspondence with Locke, however, support the latter's authorship. Knox writes his letters in Scots English, and would likely have composed poetry in the same dialect; the sonnets, however, show no grammatical or idiomatic links to Scots English.[7]

Though the volume's dedication to the Duchess of Suffolk is only signed "A.L.," Locke was probably known to the Protestant community in London, many of whom lived in exile in Geneva during the reign of Mary I or were connected with those who did.[8] By using her initials in place of her full name, Locke avoid both anonymity and complete exposure, two major transgressions that plagued female writers during the sixteenth century, who were considered unchaste if their work was published. The particular psalm translated and glossed also favors Locke's authorship. Psalm 51 states that experiencing God's forgiveness includes speaking God's praise and thus frames speech as duty, thus validating potentially dangerous female speech as spiritual obligation.[9] [10]

A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner and the Folger

The Folger holds one of two extant copies of STC 4450. The other extant copy is in the collection of the British Library. The Folger copy arrived at the library in 1938 with the purchase of the Harmsworth collection. Former owners also include R. De Coverly, whose signature is on the copy, and Alexander Moffat, marked by a bookplate.

The volume was featured in the 2012 exhibition Shakespeare's Sisters: Voices of English and European Women Writers, 1500-1700.

Notes

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Women in the Renaissance, ed. Diana Maury Robin, Anne R. Larsen, and Carole Levin, (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2007), 219.

- ↑ Micheline White, "Women Writers and Literary-Religious Circles in the Elizabethan West County: Anne Dowriche, Anne Lock Prowse, Anne Lock Moyle, Ursula Fulford, and Elizabeth Rous," Modern Philology 103 (2005):187-214.

- ↑ Susan M. Felch, "The Exemplary Anne Vaughan Lock," in Intellectual Culture of Puritan Women, 1558-1680, ed. Johanna Harris and Elizabeth Scott-Baumann (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 23.

- ↑ Susuan M. Felch, introduction to The collected works of Anne Vaughan Locke, by Anne Vaughan Locke (Tempe: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1999), lvii-lix.

- ↑ Patrick Collinson, "Locke, Anne (c. 1530-1590x1607)," last modified 2004, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, accessed March 21, 2016, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/69054.

- ↑ Michael G. Spiller, "A Literary 'First': The Sonnet Sequence of Anne Locke (1560)," Renaissance Studies: Journal of the Society for Renaissance Studies 11 (1997): 42.

- ↑ Spiller, "A Literary 'First'," 51.

- ↑ Teresa Lanpher Nugent, "Anne Lock's Poetics of Spiritual Abjection," English Literary Renaissance 39 (2009): 3-4.

- ↑ Nugent, "Anne Lock's Poetics of Spiritual Abjection," 8.

- ↑ Margaret P. Hannay, ""Wisdome the Wordes": Psalm Translation and Elizabethan Women's Spirituality," Religion & Literature 23 (1991): 65-66.