Noyses, Sounds, and Sweet Aires: Music in Early Modern England

"Noyses, Sounds, and Sweet Aires": Music in Early Modern England, one of the Exhibitions at the Folger opened June 2, 2006 and closed on September 9, 2006.

Church bells ring the time, street vendors cry out their wares, ballad singers push the latest scandal, and music spills from tavern doors: these are the sounds of London in the seventeenth century. Amidst this cacophony, even the silence of the night is broken by the bellman's ringing and accompanying call, "Past one of the clock, and a cold, frosty, windy morning."

"Noyses, sounds, and sweet aires" explores these soundscapes of early modern England, leading you through streets, into taverns and theaters, to court masques, cathedral services, and individual homes for private entertainment and personal devotion. It tells the story of the noises echoing through the city; the sounds of worlds in collision in and age of political and religious turmoil; and the sweet airs of amateurs and professionals.

The only traces of these worlds are manuscripts, books, images, and musical instruments—the material remains of musical culture. The sounds themselves have long since vanished.

Exhibition materials

Sounds of Bells: "The Perpetuitie of Ringing"

Bells marked the passage of time, day and night, in early modern England. They signaled the beginning of religious services, recorded moments of civic celebration or alarm, and tolled the death knell. They were so prevalent that they must have faded into the rest of the background noise of everyday life.

This view of London by Dutch engraver Claes Visscher was originally printed in 1616. Taken from the south bank of the Thames, where the Globe and other theaters are situated, it looks northward, showing many of the dozens of church steeples inside the city walls. Each had its own distinctive bell sound: Bow Church, St. Lawrence Pultney, St. Dustan in the East, and St. Paul's Cathedral, destroyed by the Great Fire of London in 1666.

Items included

- Claes Jansz. Visscher. Londinum florentissima Britanniae urbs. ca. 1625. Call number: GA795 L6 V5 1625 Cage and LUNA Digital Image.

Street Music: "Songs for Man, or Woman, of All Sizes"

There was no shortage of noise on the streets of early modern England. Amidst the sounds of bells ringing from steeples a pedestrian would hear street vendors shouting "cries" to hawk their wares; workmen calling out what services they offered; and everywhere ballad singers singing about the latest scandals and news. Vendors' voices needed to be loud and forceful to compete with other sounds of city life: the clop of horses' hooves, the creaking of carts, and the ringing of bells.

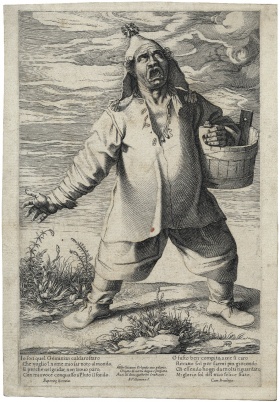

It’s hard to imagine a picture more clearly evoking the sound of a street crier than this engraving of roast chestnut seller. He flings one arm back, throws his body forward, and bellows a cry. In the poem, he claims his cry is unmatched—his voice shaking Pluto in the underworld.

Chestnuts were just one of the items sold on the streets of London by vendors. Large engravings of hawkers in books such as The Cryes of the City of London give today's readers a glimpse of some of the other common and unusual wares peddled: pins, baskets, singing glasses (a long glass cylinder fitted with reeds and a mouthpiece used as a horn), wigs, artichokes, brooms, knives, and combs.

Books containing engraved portraits of street criers, such as The Cryes of the City of London, become popular in the late seventeenth century; they evolved from individual broadsides filled with tiny figures in rows to publications of large individual portraits in book form. The brainchild of printseller Pierce Tempest, The Cryes of the City of London first appeared in 1687. This bestseller was expanded and reprinted many times until 1821.

Items included

- Francesco Villamena. Io son quel Geminian caldorostaro. Engraving, ca. 1600. Call number: ART 259- 532 (size M) and LUNA Digital Image.

Tavern Sounds: "Fidlers, Who are Properly Call'd a Noise"

Wild and raucous, English taverns were places to gather, drink, and celebrate. Amidst the laughter and occasional brawls, visitors would have heard a group, or a noise, of fiddlers playing, ballad singers crooning, and revelers singing catches and rounds while partaking of tobacco, ale, and sack (white wine imported from Spain).

It is not surprising that music books compiled for amateur use included a number of these humorous and even salacious tunes.

This collection, with words only and no music, contains ballads, songs, and catches—typical pub fare. The engraving on the title page juxtaposes upper-class and lower-class taverns.

In the top scene, Apollo dispenses "nectar" to five drinking and smoking gentlemen at an inn. In the lower, a bagpiper provides music for dancing in a tavern signed with a "rose."

Among the ballads, songs, and catches in An antidote to melancholy, there are a number that praise the virtues of carousing: "The exaltation of a pot of good ale"; "A glee in praise of wine"; "Three several songs in praise of sack"; and "The ballad of the brewer" are just a few.

Items included

- N.D. An antidote against melancholy: made up in pills. London: Printed by Mer. Melancholicus, 1661. Call number: D66A; displayed title page.

Music on Stage: "Would You Have a Love Song?"

Patrons making their way through London's streets, down to a ferry-landing on the Thames, across the water, up the bank, and through the doors of the Globe Theatre would have heard cart wheels rumbling, peddlers selling their wares, ferrymen yelling for passengers, and dogs yelping. Entering the theater, they encountered another world of sounds, a world that included music.

Music played many roles in theatrical performances: interpolated songs added layers of meaning to dramatic conversations; set pieces evoked the role of music in the real world; instrumental interludes helped set or reflect the mood.

While much of the music for the Elizabethan stage has been lost, its existence is made clear through song texts found in the plays, cues indicating performance, and references to familiar ballads and songs.

If you interested in learning more about the music heard and referenced in Shakespeare's plays, here are some selected readings on Shakespeare and theatrical music in early modern England:

- Duffin, Ross. Shakespeare's Songbook. New York: Norton, 2004.

- Folger Call number: ML80.S5 D85 2004

- Finney, Gretchen L. Musical Backgrounds for English Literature: 1580-1650. New Brunswick N.J.: Rutgers University Press, [1962].

- Folger Call number: ML3849 .F55

- Lindley, David. Shakespeare and Music. London: Arden Shakespeare, 2006.

- Folger Call number: ML80.S5 L56 2006

- Seng, Peter J. The Vocal Songs in the Plays of Shakespeare, a Critical History. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1967.

- Folger Call number: ML80.S5 S35

Additional titles for further reading can be found in the Bibliography of readings related to Noyses, Sounds, and Sweet Aires: Music in Early Modern England.

Theater during the Commonwealth

Drolls, comic scenes often excerpted from plays, were performed in ad hoc settings during the Commonwealth when theater was prohibited. Marsh published this collection after the Restoration.

The frontispiece offers a glimpse of a seventeenth-century theater: characters from several drolls populate the stage; curtains cover a place that could be used as a musicians' gallery. It is the first illustration to show an English stage lit by chandeliers and candles in front.

Items included

- The wits, or Sport upon sport. London: for Henry Marsh, 1662. Call number: W3218; displayed title page and frontis.

Music Education: "To Sing Your Part Sure"

Being able to read music, to sing a part securely, and to play an instrument were regarded as important goals for the upper classes. Amateurs learned these skills from manuals teaching the rudiments of music, or they studied with professional musicians employed as tutors.

Instruction often began with the gamut, the musical scale comprised of letters and solmization or solfa syllables (similar to our do re mi ) designating the degrees of the scale. Students were advised to "Learne Gam-ut up and down by heart."

John Dowland (1562–1626) was the greatest English composer of his time for the lute, writing solos, songs, and music for five viols and lute. Folger manuscript V.b.280 is called "The 'Dowland' lutebook" because it contains signatures and other examples of Dowland's handwriting and just might have been in his family until sold to Henry Clay Folger in 1926. The manuscript contains many easy pieces, still used by lute teachers today, as well as some of the finest music for very skilled players. Dowland, the last of three main copyists in the book, entered only three pieces; the final one is incomplete.

The Compleat Gentleman

In this popular conduct book, The Compleat Gentleman, Peacham includes a chapter on music education (it falls between chapters on poetry and on painting and drawing).

Offering very practical advice, Peacham admits, "I desire no more in you then to sing your part sure and at the first sight, withall, to play the same upon your Violl, or the exercise of the Lute."

His list of composers worthy of emulation is interesting: William Byrd is included along with Peacham's Italian music instructor Orazio Vecchi. Italian music was particularly popular at the turn of the seventeenth century.

Items included

- John Dowland. Collection of songs and dances for the lute. Manuscript, ca. 1594-ca. 1600. Call number: V.b.280 and LUNA Digital Image.

- Henry Peacham. The compleat gentleman fashioning him absolute in the most necessary & commendable qualities concerning minde or bodie that may be required in a noble gentleman. London, 1622. Call number: STC 19502 Copy 1; displayed f. A2.

Music Printing: "A Perfect and True Copie"

The technology for printing music from movable type was developed in about 1500 in Italy. In the 1520s the English printer John Rastell began using the single-impression method. This technique, which uses type fonts with both notes and staves, made commercial music printing possible.

England, however, did not become a major center for music printing, perhaps because of the systems of control exercised by royal patents and by the Company of Stationers. Printers found various means to get around these restrictions, including the printing of “hidden editions.”

When students of music and of early modern history look at early editions of music publications, it is important for them to have a clear understanding of the ways music was printed, performed, and collected from the sixteenth century up until today.

Printing

Music books were usually printed as partbooks, each one containing the music for a single voice part (cantus, altus, tenor, etc.). This partbook contains the music for the cantus part.

Performing

Each singer or instrumentalist would read from the music book for his or her part.

Click on this image and get a view of these musicians, each playing from their own partbook.

Collecting

Music books were typically short—sometimes containing as few as twenty leaves. Owners often had several titles bound together as a set, known as a “binder’s copy.” All of the titles in one volume of a binder’s copy contain the music for a single part, i.e. altus or bassus, etc. This volume comprises the altus parts of six books of madrigals. Along with the Quintus, it is only one of two volumes that survives from a set of five that once belonged to Sir Charles Somerset (ca. 1588–1665).

By the nineteenth century, many binder’s copies were coming apart. Collectors such as Henry Huth (1815–1878) had them disbound and all the parts for a single work bound together in one volume. This new binding preserved the complete set, but the music could no longer be used for performance.

Items included

- Orlando Gibbons. First set of madrigals and mottets of 5. parts: apt for viols and voyces. London: Printed by Thomas Snodham, 1612. Call number: STC 11826 Copy 2; displayed title page.

- Nieuwen Jeucht Spieghel. 1620. Call number: PN6349 N65 1620 Cage and LUNA Digital Image.

- Thomas Weelkes. Madrigals to 3.4.5. & 6. voyces. London: Printed by Thomas Este, 1597. Call number: STC 25205 Copy 2 Vol. 1; displayed cover.

Playford and New Markets: "A Much Larger Banquet than You had Before"

The abolition of the Book of Common Prayer services in 1645 and the dissolution of royal and cathedral musical organizations during the Commonwealth forced professional musicians into private employment as music tutors and helped to develop a broad-based audience of enthusiastic musical amateurs. Stationer John Playford shrewdly provided music for this new market—instruction manuals, country dances, catches, songs, and psalms. A committed royalist, he used music to help sustain royalist aspirations during the Interregnum.

Some of Playford's most popular titles included:

- The English Dancing Master (1651)

- A Musicall Banquet (1651)

- Catch that Catch Can (1652)

- Musicks Recreation (1652)

- Introduction to the Skill of Musick (1654)

- Court Ayres (1655)

As a stationer and a musician, Playford was particularly suited to collect and promote music. He possessed some training and a genuine interest in music. Consequently he seems to have been accepted in London musical circles where could easily copy music from friends and associates.

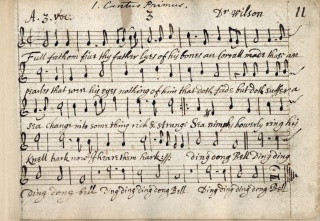

The manuscript above is an example of Playford's musical copying used for singing and playing with his music club. It records a version of Robert Johnson’s "Full fathom five," most likely written for a Jacobean re-staging of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Although Playford and Johnson never met, Playford probably received the piece from Johnson’s fellow theater musician John Wilson.

In this pastoral elegy for Playford, written by Nahum Tate and set to music by Henry Purcell, the shepherds are entreated to lament Playford in the guise of Theron. King Theron of Acragus (488-472 BCE) was an ancient Greek ruler known for promoting the arts. Such a tribute to Playford demonstrates the high esteem with which he was regarded by Restoration artists.

Items included

- John Playford. John Playford collection of music to The Tempest. Manuscript, ca. 1650-1667. Call number: V.a.411; displayed p. 11r.

- Nahum Tate. A pastoral elegy on the death of Mr. John Playford. London, 1687. Call number: T203; displayed title page.

Viols: "Strike Up a Noise of Viols"

Introduced into England early in the sixteenth century, the viola da gamba, a fretted instrument of six strings played with a bow, became extremely popular among both professional and amateur musicians. Valued in part because of its shimmering sound, the viol was also relatively easy to learn and soon became a staple of domestic music-making.

While composers wrote fantasias and other kinds of instrumental music specifically for viol consorts (or ensembles), performers also played vocal music, often advertised as "apt both for viols and voyces," on these stringed instruments.

Items included

- John Strong. Treble viol. England, 16th century?. Call number: ART Inv. 1047 and LUNA Digital Image.

- [Bass viol]. Call number: ART Inv. 1048 and LUNA Digital Image.

Music at Court: "Greet Elyza with a Rhyme"

Queen Elizabeth, indeed every monarch, had a special role in the national musical culture. The court maintained the Chapel Royal, a group of musicians and clergymen serving the English monarch, as well as a large number of instrumentalists.

Elizabeth was known as an accomplished amateur musician; she was even portrayed in one portrait holding a lute, the most popular aristocratic instrument of the day. Her influence on music can be seen through her patronage of Tallis, Byrd, Ferrabosco, and Morley.

During the reign of James I, court masques came into vogue. These entertainments were dramatic pageants, incorporating drama, music, dance, ornate costumes, elaborate scenery, and complex allegorical and political meaning. Produced by and for the monarch and the court, masques were designed to praise rulers, likening them and their courtiers to mythical gods and heroes. By spending lavishly on productions, monarchs like James I, and other sponsors showcased their affluence. Because of the ephemeral nature of masques, only bits and pieces survive from what must have been a vast corpus of vocal and instrumental music produced for them.

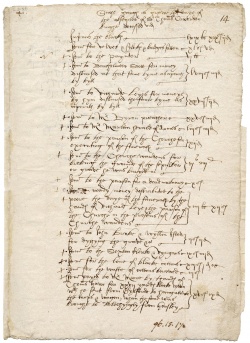

This unpublished manuscript shows the organization of the musical establishment typical since the time of Henry VIII. The categories of musicians include those involved with ceremonies of state (“trumpeters”) as well as instrumental ensembles and other musicians: “Luters,” “Harpers,” “Singers,” "Rebecke” (fiddle family), “Sagbutts” (trombone family), “Vialls,” “Bagpiper,” “players of Enterludes,” “Maker of instrumentes.” The only name listed, “Browne,” is that of Benedict Browne, “Serjeant Trumpetter.”

Items included

- A generall collection of all of the offices in England. Manuscript, 1609. Call number: V.b.119; displayed p. 22 recto.

- Lute. Workshop of Michielle Harton. Padua, c.1598. Call number: ART Inv. 1002 (realia) and LUNA Digital Image.

Worship in Times of Religious Strife: "O Sing unto the Lord a New Song"

Changes in the English church begun during Henry VIII’s reign, initially more concerned with economics and politics than with theology, turned during Edward VI’s reign into a wholesale assault on the “Old Religion.” The apparatus of the liturgy—including music books used in Latin services—and the institutions that had supported it were destroyed.

In this Catholic Book of Hours, the iconoclastic fury of some reformers in England during this period is evident. The book is defaced; a reader has crossed out references to the Pope as well as to indulgences such as one earned by "say[ing] .iii. times the hoole salutacyon of our lady." Books of Hours—primers containing prayers for lay devotion—were Catholic "bestsellers."

After Edward’s death, Mary I re-instituted Catholic observance, while Protestants, now in exile, were absorbing practices of Calvin’s Geneva.

Images such as this one, depicting the "persecution of Catholics by Protestant Calvinists in England," were designed to inflame. In this engraving, martyrs are drawn on hurdles to the place of execution, hanged, drawn and quartered, and burned; their heads were displayed on Bridge Gate, at the south entrance to the city.

When she became queen, Elizabeth I re-established the Book of Common Prayer, and composers began creating music for an English church that would offer a distinctive blend of traditional and reformed practices.

Items included

- [Book of Hours (Salisbury)]. Hore Beatissime virginis marie ad legitimum Sarisburiensis Ecclesie ritum, cum quindecim orationibus beate Brigitte, ac multis alijs orationibus pulcherrimis, et indulgentijs, cum tabula aptissima iam ultimo adiectis. Paris, 1530. Call number: STC 15968; displayed f. Liiii.

- Richard Verstegan. Théatre des cruautez des heretiques de nostre temps. [Antwerp, 1588]. Call number: BR 1605 V4 1607 Cage; displayed p. 80-81.

Psalms in Church and at Home: "If Any of You Be Mery Let Hym Synge Psalmes"

It is hard to overestimate the importance of psalm singing in early modern England. Chanted Latin psalms had played an essential part in Roman Catholic worship, but with the coming of the Reformation, metrical psalms in the English vernacular were introduced for congregational singing. Psalm books became treasured possessions of nobility and commoners alike, to be used both in church and in family prayers. They were published in more than 1,450 editions over 300 years.

The so-called “Old Version” of the English psalter appeared in over 450 editions with tunes between 1562 and 1688, in sizes from large to small. Many, like this edition, were bound with bibles or prayer books. The small, dos-à-dos binding reflected the Puritan principle that women as well as men should sing. Festooned with decorative embroidery, it could be easily carried in a purse.

This partbook is one of a collection of five original settings by Henry Lawes and his late brother William, who was killed fighting for Charles I at the siege of Chester in 1645. The texts are psalm paraphrases by George Sandys, set as vocal chamber music. The dedication shows that Lawes, one of Charles I's court musicians, was unafraid to advertise his loyalty even at this late date.

Items included

- The whole booke of Psalmes: collected into English meeter by T. Sternhold, I. Hopkins, W. Whittingham, and others, conferred with the Hebrew, with apt notes to sing them withall. Newly set foorth, and allowed to be sung in all churches, of all the people together, before and after morning and euening prayer, as also before and after sermons. Moreouer in priuate houses, for their godly solace and comfort, laying apart all vngodly songs and ballads, which tend onely to the nourishing of vice, and corrupting of youth. London, ca. 1610. Call number: STC 2535.2 Bd.w. STC 2907 and LUNA Digital Image.

- Henry Lawes. Choice psalmes put into musick, & for three voices. London, 1648. Call number: L640; displayed title page verso.

Sounds of Mourning: "For Whom the Bell Tolls"

What is the sound of mourning? In early modern England, the toll of a bell, rung once for each year of a person’s life, announced death and called mourners to funerals.

These funerals, or obsequies, could be lavish. This manuscript details the spectacle of a knight’s funeral, including expenses for attire and banquet as well as payments to preacher, herald of arms, grave diggers, and “ryngars.” Typically, bells were rung right after a person’s death as well as before and after the burial. A ringer tolling the “lich bell” might accompany the corpse in a funeral procession.

Death also inspired powerful musical responses, found in the elegies that composers wrote for departed friends, teachers, and patrons. Like the tolling of bells, these musical tributes captured the sound of a person, a community, or a nation in mourning.

Items included

- William More. Suche charges as grewe the daye of the obseques of Sr Thomas Cawerdon Knight decessed. Manuscript, ca. 1559. Call number: L.b.86 and LUNA Digital Image.

Supplemental materials

"Noyses, Sounds, and Sweet Aires": Music in Early Modern England children's exhibition

Related publications

A companion catalog, "Noyses, sounds, and sweet aires" : music in early modern England, compiled and edited by Jessie Ann Owens was published in conjunction with the exhibition and can be purchased from the Folger Shop. Found at Call number: ML286.2 .F65 2006, the book includes an introduction by Owens as well as the following critical essays:

- "What means this noise?" by Bruce R. Smith

- "Ballads in Shakespeare’s world" by Ross W. Duffin

- "John Playford and the English musical market" by Stacey Houck

- "Music and the cult of Elizabeth : the politics of panegyric and sound" by Jeremy Smith

- "Reading between the lines : Catholic and Protestant polemic in Elizabethan and Jacobean sacred music byCraig Monson

- "If any of you be mery let hym synge psalmes" : the culture of psalms in church and home by Nicholas Temperley