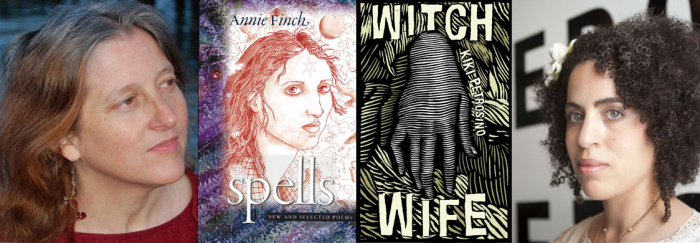

I Put a Spell on You (2019)

Part of the O.B. Hardison Poetry Series, I Put a Spell on You featured poets Annie Finch and Kiki Petrosino reading from their work in the Folger's Elizabethan Theatre on October 28, 2019 at 7:30pm. The two poets explored the realms of witchcraft and womanhood in all seasons of life.

The reading was preceded by a pop-up exhibition in the Paster Reading Room, which featured items from the Folger collections releated to witches, witchcraft, spells, and magic. The pop-up was curated by Teri Cross-Davis, Poetry Coordinator, and Beth DeBold, Assistant Curator of Collections. For more information on this past event, please visit the event page.

The exhibition catalog is available for download as a PDF file.

Items included

1). Shakespeare, William, 1564-1616

Mr VVilliam Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies: Published According to the True Originall Copies.

London: Isaac Jaggard and Ed. Blount, 1623

Call Number: STC 22273 Fo.1 no.72

Binding images for STC 22273 Fo.1 no.72

After William Shakespeare died in 1616, two friends from his acting company put together the history-making book that's best known as the "First Folio" of Shakespeare. Published in 1623, seven years after his death, it contains 36 of Shakespeare’s plays---almost all of them. Eighteen of the plays, including Macbeth and Twelfth Night, had never been published before and may have been lost without the creation of the First Folio. Largely because of this book we know them all. A “folio” was a large, expensive book, usually reserved for Bibles or important works of history, law, and science--- not plays. Shakespeare was one of the first English playwrights to have his plays collected in a folio.

The Folger owns 82 copies of this first printed edition of Shakespeare’s works. This copy once belonged to Rachell Paule, a woman living in 17th-century London.

Text by Caroline Duroselle-Melish

2). Bell, Robert Anning, 1863-1933

Trio of illustrations from Bell’s edition of The Tempest

[1900]

Call Numbers:

ART Box B433 no.7 (size S)

ART Box B433 no.10 (size S)

ART Box B433 no.20 (size S)

Although many of Shakespeare’s plays feature magic and the supernatural, The Tempest is the only one to deal so directly with characters who are human practitioners of magic. These original pen and ink illustrations were made by Bell for his edition of the play, published in 1901. We never meet the witch Sycorax in the real time of the play, but she casts a long shadow—the dead mother of the monstrous Caliban, her wickedness and depravity in her use of magic make her the perfect foil for the supposedly beneficent sorcerer Prospero.

Here, Caliban is portrayed as half fish, half man—reminiscent of a sea monster. In Bell’s Frontispiece to Act I, we see him before the arrival of Prospero on the island and his subsequent enslavement, sitting with the spirit Ariel who has been imprisoned in a pine tree by Sycorax. Bell also provides us with an illustration of the witch, described in the play as a “blue-eyed hag.” Contrast the two with Bell’s depiction of a freed Ariel. Scholars have long noted the racialized and gendered tensions present in the play, which was written in 1611, at the beginning of England’s colonial depredations in the Caribbean. These themes, as well as the tensions present in Bell’s early twentieth century, are evident in these illustrations.

Sycorax and Caliban are two characters that have lived rich lives outside the bounds of Shakespeare’s words, inspiring novels, plays, poems, and art from the 19th century on.

Text by Beth DeBold

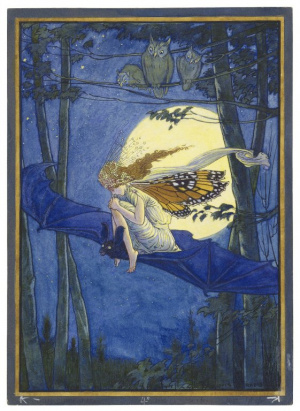

3). Rhead, Louis, 1857-1926

[Ariel on a bat’s back]

[before 1918]

Call Number: ART Box R469 no.108 (size L)

Ariel, the lively spirit who is freed from the witch Sycorax only to be bound by the sorcerer Prospero in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, has long been an inspiration for artists. In Act V, Prospero asks Ariel to help attire him in preparation for his final confrontation with Antonio, Sebastian, and Gonzalo. He promises that once this final reckoning is made, Ariel will be free from his magical bonds. In response, Ariel sings:

Where the bee sucks, there suck I,

In a cowslip’s bell I lie;

There I couch when owls do cry;

On the bat’s back I do fly

After summer merrily.

Merrily, merrily shall I live now

Under the blossom that hangs on the bough.

(Act V, sc.i 98-104)

This watercolor illustration was painted by artist Louis Rhead in preparation for a 1918 edition of Charles and Mary Lamb’s Tales from Shakespeare. This popular and often-reprinted volume offered prose retellings of Shakespeare’s plays, and was primarily meant for children.

Text by Beth DeBold

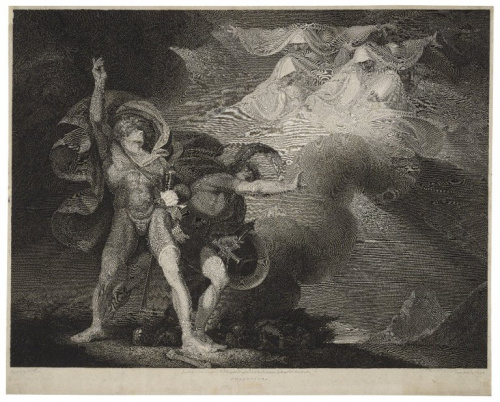

4). Trotter, Thomas, printmaker, 1756-1803; after Henry Fuseli, painter, 1741-1825

[The Witches appear to Macbeth and Banquo]

London : J. & J. Boydell, 1790

Call Number: ART Box F993 no.9 (size XL)

In this vivid depiction of Macbeth and Banquo’s encounter with the three Weïrd Sisters on the blasted heath, we are thrown into the chaotic moment at which Macbeth learns his fate: the three sisters cry “hail,” telling him that he shall be Thane of Cawdor, and king thereafter. Troublingly, they also prophesy that Banquo “shalt get kings, though [he] be none.” Shortly after, the two are met by King Duncan’s men, who hail Macbeth as Thane of Cawdor. Macbeth begins to wonder if, since this part of the prophecy was true, how the rest might be fulfilled. From this one moment, his path is set towards the inevitable: murder, doom, and ruin.

Henry Fuseli, a Swiss-born painter who lived in England for much of his life, was captivated by the macabre and supernatural. In 1786 he was commissioned to paint scenes from different Shakespeare plays for engraver and publisher John Boydell’s famous and ill-fated “Shakespeare Gallery.” Meant to foster British art and create a large, lavishly illustrated folio edition of the plays, as well as engraved reproductions of the paintings for sale, the gallery ended up being a financial failure—but it had an enormous influence on the public, perceptions of Shakespeare, and how art was made and consumed in Britain. This engraving is a proof, prepared for a print that was never published.

The Folger owns several original Fuseli paintings, including depictions of Ariel, Puck, “Faery Mab,” and “Macbeth Consulting the Vision of the Armed Head.” These are currently on display in the Bond Reading Room, along with other works of art from the Folger collections.

Text by Beth DeBold

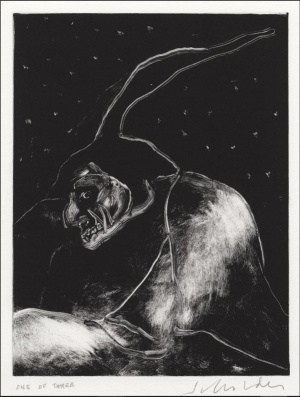

5.) Scholder, Fritz, 1937-2005

One of Three

1995

Call Number: ART 240183 (size L)

This gorgeous monotype depicts “one of three” witches from Macbeth. Clad in a horned helmet and thick cloak, thick tusks sprouting up from her lower jaw, the witch gazes back at us out of the corner of one eye from under a carpet of stars.

Montoype prints are a magic in and of themselves—they are created by painting in reverse on a glass or acrylic plate with ink, or by covering the plate in ink and then removing the portions meant to be negative space. A single print is then made using a press. The result is one-of-a-kind, and can never be repeated in quite the same way again. Monotypes are particularly prized for their velvety, textured quality. Sometimes a single print will pass through the press multiple times as color and lines are added.

Scholder’s creation here captures the shivery delight often evoked by the Weïrd Sisters…and makes us wonder what the other two are up to in the meantime.

Text by Beth DeBold

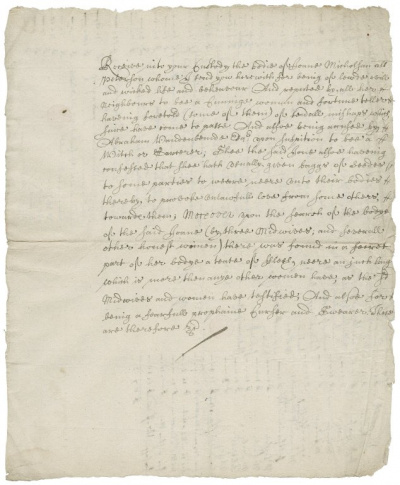

6.) Unknown

An paramount for to get the love of a woman [and two other spells]

England: [1600]

Call Number: X.d.208

High-resolution Digital Images of X.d.208

This document includes several spells, including a spell to “get the love of a woman,” “To know when a woman is w[i]th a man chylde or a woman chylde,” and “To know whether newes be trow or false.”

The first and lengthiest spell instructs the bearer in how to conduct a coercive love spell. First, the person wishing to use the spell must draw the image “of ^a woman her whom thow doste love / or whom thow wylte haue” on a blank tile on a Friday. The caster must then offer specific words and prayers to both Venus and God. The spell gives helpful guidance in how to draw the object of the person’s desire, along with specific symbols to include, where to place them, and what they mean. If the worker of this spell is successful, the woman will have “nether reste in slyppynge nether wakynge…lyenge nether standdynge nether settynge & how so ever she move that so she maye burne in the love [of him] & that she maye so thynke vppon hym contynyally wth owte sessynge, where by she maye com & full fyll his wysh & re queste in all thynges…”

Text and transcription by Beth DeBold and Heather Wolfe

7). Unknown

Book of Magic, with instructions for invoking spirits…

England: [1577-1583?]

Call Number: V.b.26 (1) and (2)

Cover-to-cover digital images of V.b.26 (1)

Cover-to-cover digital images of V.b.26 (2)

The Book of magic, ca.1577–1583 V.b.26, page 51

This grimoire contains detailed instructions for invoking spirits and casting spells. Through the magic of various invocations, the user could cure sickness, catch thieves, or find love. The manuscript was well-used: successive generations of readers added notes to the margins, and one user supplied page numbers in a distinctive blue ink. In the early nineteenth century, the first fourteen pages and the final thirty pages were removed, and the Folger Shakespeare Library purchased this incomplete version of the manuscript in 1958. We were able to add the missing final pages to the collection after successfully bidding on them at a 2007 auction in London. This ‘lost’ portion of the grimoire was identifiable by its blue page numbers and other external and internal evidence. We are still searching for pages one to fourteen.

Magic circles were drawn on the ground or on a piece of parchment in order to summon angels, spirits, or demons to assist the magician with his work. In the volume to your left, V.b.26 (1), the two circles are to be used to summon the spirit Birto “to make aunswere to any Question to be demaunded” on the second, fourth, sixth, tenth, or twelfth day of the month, when the air is clear. The summoner was instructed to sit in the right-hand circle on his knees and repeat three times the provided prayer, psalm, and conjuration. Birto would then appear in the form of a man in the other circle. On the opposite page, instructions in Latin are written for summoning a spirit named Bilgall.

In V.b.26 (2), to your right, the ABRACADABRA spell appears on the bottom of page 206, the first page of the last part of the manuscript which the Folger acquired in 2007. A magician could cure a sick person without that person’s knowledge by each day scraping out successive lines of the word ABRACADABRA, written on virgin parchment, while reciting the provided spell.

Text by Heather Wolfe

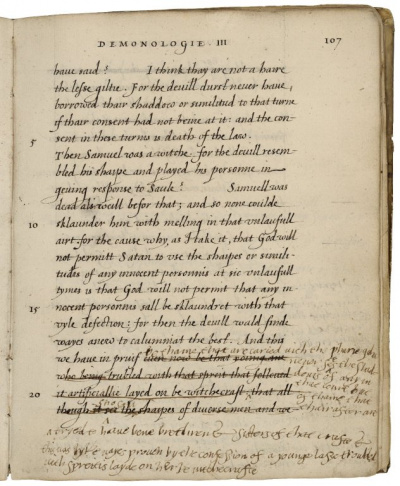

8). James I/VI, 1566-1625

Daemonologie in form of a dialogue [manuscript]

[1592]

Call Number: V.a.185

Select Images of V.a.185

This manuscript is a fair copy of a treatise written by King James I/VI on witchcraft and demonology. He was quite interested in the supernatural, and when in 1590 it was revealed that several witches in North Berwick (just east of Edinburgh) had made attempts on his life, he traveled to both attend the trials and interrogate the witches himself. Daemonologie follows the form of a conversation between two fictional individuals, “Philomathes” and “Epistemon,” who debate what is known about witchcraft. It was published in 1597, and issued three times in London on his accession to the throne in 1603. It was also made available in Latin and Dutch for international audiences. Daemonologie also pushes back against those who doubt the existance of witches, particularly the author Reginald Scot, whose book The Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584) characterized belief in supernatural phenomena and witchcraft as irrational. In his text, James criticizes Scot roundly, his book was banned, and copies burned.

This scribal copy of Daemonologie has been attributed to James’s childhood friend Sir James Semphill, and contains corrections in the hand of the monarch himself.

Text by Heather Wolfe and Beth DeBold

9.) Unknown

Spell to bind the seven sisters of the fairies to you for ever

England: circa 1600

Call Number: X.d.234

High-res Digital image of front side of X.d.234

Written on vellum, this highly unusual and unique set of four spells instructs the bearer in how to summon and bind the fairies Lilia, Hestillia, Fata, Sola, Afrya, Africa, Julia, and Venulla. The first spell gives instructions for calling the fairies, the second another set of instructions for marking a circle and calling individual fairies to you, the third for binding them once they are in your presence, and the fourth to banish them. The reason for calling the fairies is explicitly for sexual purposes. This manuscript is considered at length in Dr. Frederika Bain’s article “The Binding of the Fairies: Four Spells," which can be viewed and downloaded here.The article includes full transcriptions.

Text by Beth DeBold

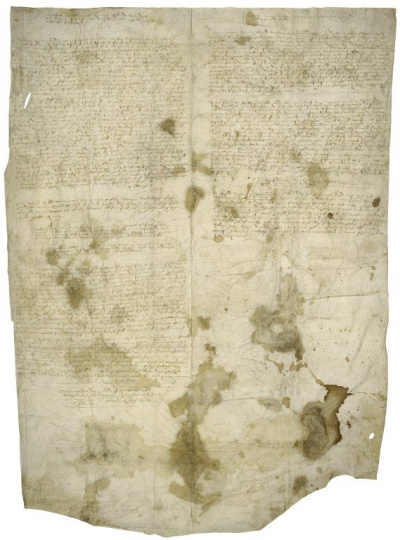

10.) England and Wales. Court of Quarter Sessions of the Peace.

Warrant from the Middlesex Court of Quarter Sessions of the Peace for imprisonment of Joane Micholson

England: [1675?]

Call Number: X.d.375 (30)

High res Digital Image of X.d.375(30)

This undated warrant provides a glimpse into the process of accusation and arrest on suspicion of witchcraft. The victim’s name is Joan Micholson. The document reads:

Receive into your Custody the bodie of Joane Micholson als

Peterson whome I send yow here with for being of lewde evill

and wicked life and beheavour And reputed by all her

Neighbours to bee a Cunninge woman and fortune teller

haveing foretold (some of them) of sem ill mishaps which

Since have come to passe. And alsoe being accused by

Abraham Pandenbende Esq^r vpon suspition to bee a

Witch or Sorcerer; Shee the said Jone also having

confessed that shee hath usually given baggs of seedes

to some parties to weare neere vnto their bodies

thereby to provoke unlawfull love from some others,

towarde them; Moreover vpon the search of the bodye

of the said Joane (by three Midwives; and several

other honest women) there was found in a secret

part of her bodye a teate of flesh neere an inch long

which is more then anye other woman have, as the s[ai]d

Midwives and women have testified, And alsoe for

being a fearfull prophaine Curser and Swearer, These

and therefore &d./

The narrative hits all the usual marks of a seventeenth-century witchcraft accusation: Joan is able to predict the future; she is known to provide love charms; she curses, swears, and behaves badly; furthermore, when examined by midwives and “honest women,” she is found to have a teat where a familiar or the devil might be expected to come nurse. While most victims accused of witchcraft were women, women also participated heavily in trials as experts on women’s bodies, and participated in accusing their neighbors. Joan’s fate is not known.

Text and transcription by Beth DeBold

11.) Molitor, Ulrich, 1470-1501

De Lamiis et Phitonicis Mulieribus

Germany, circa 1493-1500

Call Numbers:

INC M794

INC M795

INC M803

INC M806

These items have not yet been added to our digital collections

De Lamiis et Phitonicis Mulieribus ("Of witches and diviner women") was an early treatise on witchcraft, which featured some of the first illustrations of witches in European sources. These four books were printed in what is now Germany—two in Latin, and two in the local language.

First published in 1489, De Lamiis is a dialogue between a skeptic (Archduke Sigismund of Austria) and a believer (the author Molitor) in witchcraft. Molitor believed that the Devil had the power to trick people into giving him allegiance, and that most resulting magical phenomena credited as witchcraft were illusions caused by Satan to keep humans in thrall. He did not trust witches who confessed through torture, although he did advocate for the execution of witches as heretics.

The lively woodcuts show witches working weather magic, copulating with a demon (possibly the Devil himself), transforming into evil creatures, and engaging in a sabbath, Such images established the popular idea of what witches looked like, which can still be seen today. These four volumes are on deposit at the Folger through the generosity of Ingrid Rose, in memory of Milton Rose.

Text by Beth DeBold

12). Napkyn, Hugh, active 1617-1639

A booke conteyning divers excellent & approoved remedyes in phisique and chyrugery…

England: [1631]

Call Number: Fast Acc. 271103

This item has not yet been added to our digital collections

Compiled by Hugh Napkyn, a barber surgeon living in London in the seventeenth century, this elaborate manuscript contains numerous recipes for plasters, balms, waters, and other medical remedies. The cures treat a wide variety of complaints and illnesses, from simple coughs to “cancer in the breast” and the plague. The boundaries between medicine, food, science, and magic were much more porous than we would think of them today: for example, this charm for an Ague, which involves carving mystical characters into two halves of a pippin (a type of apple). The patient is then supposed to eat in a specific way, and Napkyn writes that it has been “prooved [successfully tested] numerous times.” It is perhaps worth mentioning that Napkyn was involved in several medical malpractice suits, but it was not uncommon for medical practitioners to utilize such charms.

Text compiled from dealer description

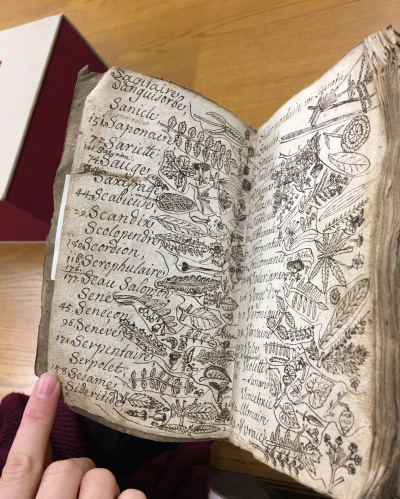

13.) Unknown

Table des plantes naturelles de l’evêchée des Bâles qui entrent en Medecine…[manuscript

[Basel]: circa 1700

Call Number: V.a.597, item 1

This item has not yet been added to our digital collections

This beautifully-illustrated French manuscript provides lists of plants found in the “bishopric of Basel,” which can be used for medicinal purposes. In the early modern period, medicine, cookery, magic, and science were more fluid categories than how we think of them today, and manuscript miscellanies such as this one would routinely include recipes to both cure and feed the body. Some recipes may seem less based on scientific logic as we would understand it today, and more like what we would think of as “magic.” The table of detailed illustrations, helpful for recognizing the plants, is followed by an index of common ailments (for example, ulcers, gout, or paralysis) and potentially afflicted body parts (eyes, stomach, intestines). The book further includes descriptions of each plant listed, and its uses. Plants named include ones we would consider both medicinal and culinary, such as Chicory, White and Black Hellebore, Endives, Chamomile, Aniseed, Mint, Vervain, and Sesame. In addition to cures for humans, the manuscript also includes cures for farm animals.

Text by Beth DeBold