Lost at Sea: The Ocean in the English Imagination, 1550–1750

Lost at Sea: The Ocean in the English Imagination, 1550–1750, one of the Exhibitions at the Folger, opened June 10, 2010 and closed on September 4, 2010. Lost at Sea was curated by Steve Mentz of St. John’s University with Carol Brobeck of the Folger Shakespeare Library.

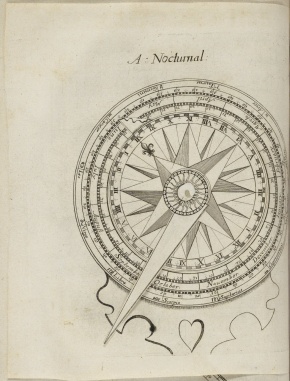

Being at sea means having no clear place in the world. Faced with the featureless, boundless ocean, early modern mariners learned that living and working in this space required both conceptual and technical labor. Sailors employed practical navigational technologies including compasses, astrolabes, and maps, and also conceptual frameworks such as Providential theology, literary narratives, and the early stages of empirical science. They needed to navigate complex networks of winds and currents, and they also needed to understand the watery depths that buoyed them up.

This exhibition explores the tools English mariners and writers used—from atlases, sextants, and star charts to prayer-books, symbols, and stories—to find themselves on changing oceans.

Curation

Lost at Sea was curated by Steve Mentz. Mentz is Associate Professor of English at St. John’s University in New York City. He is the author of At the Bottom of Shakespeare's Ocean (2009), two additional monographs, and numerous articles on Shakespeare, ecological criticism, maritime culture, and related topics. He was the recipient of a short-term fellowship at the Folger Shakespeare Library which, he reveals in his book’s acknowledgments, “contains more real salt than many think.”

Curator's insights

The following is an excerpted podcast transcript of Steve Mentz's July 13, 2010 lecture entitled "Lost at Sea: At the Bottom of Shakespeare’s Ocean." The article Scholars' insights provides the entire transcript and as well as a link to the full podcast of this lecture.

What I’m going to try to offer over the course of this talk tonight, is some essential features of the ocean as human beings can partially understand it. And I want to suggest that this isn’t actually as strange and academic as it might seem. I want to suggest that this is actually the way we encounter the ocean when we go to the beach on vacation. We just don’t always articulate it. And so on the one level I’m trying to bring together some historical literary material, and I’m also trying to capture the feeling that we each have when we stand on the beach and we look at the ocean and we have that little feeling of difference or slight dislocation, of being in the presence of the largest thing on the planet.

So, I’m going to try to outline three primary features of the ocean as it, as it appears in a poetic or historical sense. First of all that the ocean is opaque and it resists our seeing through it. Second of all, and this is a phrase that I get from Shakespeare, that the ocean is hungry, and third, that the ocean is transformative. It transforms itself and it transforms us.

Living on land we sometimes forget how much the sea’s physical structures control our physical and cultural histories. We should remember.

It’s true that poetry can’t keep oil out of the Gulf, or protect low lying cities from tropical storms, but it’s also true that language is one of the basic tools that our culture uses to grapple with our unstable ocean drenched environment. Shifting away from the supposed stability of land will cause us to abandon certain kinds of happy fictions and replace them with less comforting narratives. Fewer insular Tahitis and more ship wrecks. But, and this is really my key point, both in the talk tonight and the exhibition outside, and also in the book. We already have these narratives. We just don’t always put them at the center which is where they belong. The trick going forward will be to replace the tragic narrative of humanities failed attempts to control nature with less epic, more improvisational stories about working with an intermittently hostile natural world. We need stories about sailors and swimmers and divers to supplement our over-supply of warriors and emperors. These stories are already there, Odysseus swims to shore from his wrecked ship, Ishmael survives the destruction of the Pequod, Robinson Crusoe thrives on his island home. In Shakespeare Marina, Ferdinand, and Viola all survive immersion even if Othello, Timon and Lear do not. These are stories we can use.

When we look for the sea we see it. It’s always there. We may not understand the waters, but we know where to find them. The sea’s overwhelming presence in our physical and imaginative worlds gives us reasons to reread Shakespeare and Anglo-American history with salt in our eyes. Think about how our fears of flood spill into semi-opaque affirmations and transformations. Because these stories unfold the rich and strange history of our imagined relationship with the biggest thing on the planet, Shakespeare’s ocean and the oceans in Lost at Sea are shifting symbols whose meanings are never exhausted their unreachable bottoms conceal treasure and promised death. Reading Shakespeare for the sea thus launches the vast and slightly quixotic project that I call Blue Cultural Studies. A way of looking at our own terrestrial culture from an offshore perspective. As if we could align ourselves with the watery element. What we will find is a painful and joyful history of coming to terms with a world of flux. Shakespeare and Lost at Sea ask us to read as if poetic narratives and the poetical imagination can help us embrace and endure ocean driven disorder. Whether we can always imitate Shakespeare’s shipwreck survivors or Melville’s whalemen or Robinson Crusoe isn’t certain, but as our world goes bluer and less orderly, these stories have something that we need.

Listen to excerpts of Steve Mertz's lecture.

Contents of the exhibition

Lost at Sea exhibition material

This article offers descriptive list of some of the items included in the exhibition.

Scholars' insights on Lost at Sea

This article includes the podcast and transcript of lectures given by Alden Vaughan, Steve Mentz and Virginia Lunsford with the theme of Stories of the Sea.

Lost at Sea children's exhibition

Supplemental materials

Multimedia: A Mercantile View of the Ocean

The Atlas maritimus & commercialis puts the world's oceans into one large box. Weighing over 20 lbs, the book includes geographic descriptions probably written by Daniel Defoe, plus 52 maps. Its nearly 300 wealthy subscribers comprise a who’s-who of the British maritime elite, from merchants to naval administrators to the Governor of Bermuda. Explore six regions of this watery and commercial globe on this interactive website.

Audio Tour

Steve Mentz, curator of the exhibition, shares insights into a selection of items from the exhibition. Much of this audio can also be found within the article, Lost at Sea exhibition material.

A Mariner's Toolkit

Listen to an explanation of the navigational elements in the title page of The Mariners Mirror.

- Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer. Spieghel der Zeevaerdt (The Mariners Mirrour: wherin may playnly be seen the courses, heights, distances, depths, soundings, flouds and ebs, risings of lands, rocks, sands and shoalds, with the marks for th’entrings of the harbouroughs, havens and ports of the greatest part of Europe: their several traficks and commodities: together wth. the rules and instruments of navigation). London: John Charlewood, 1588?. Call number: STC 24931 and LUNA Digital Image.

The Cruel Seas

Hear about one memorial poesy rings and one ring in particular.

- [The cruell seas, remember, Took him in November, 92]. Memorial poesy ring. Ring in memory of one who went to sea. Gold, rock crystal and textile, [1592?]. Call number: H–P Reliques no.9 (realia) and LUNA Digital Image.

Maritime Triple Threat

Hear more about John Davis and his invention, the "Davis Staff."

- John Davis. The seamans secrets. London: John Dawson, 1626. Call number: STC 6370 and LUNA Digital Image.

Winds and Currents

Hear Steve Mentz explore the mysteries of winds and currents.

- Edward Barlow. Meteorological essays, concerning the origin of springs, generation of rain, ... In two treatises. London: for John Hooke; and Thomas Caldecott, 1715. Call number: QC859.B3 Cage and LUNA Digital Image.

Salvation on the Sea

Hear more about James Janeway's theology of salvation on the sea.

- James Janeway. A token for mariners, containing many famous and wonderful instances of God’s providence in sea dangers and deliverances. London: for T. Norris, and A. Bettesworth, 1721. Call number: BV4590.J3 1721 Cage and LUNA Digital Image.

The Book-Fish

Listen to curator Steve Mentz discuss The Book–Fish.

- John Frith. Vox piscis: or, The book–fish contayning three treatises which were found in the belly of a cod-fish in Cambridge Market, on Midsummer Eve last, anno Domini 1626. London: [Humphrey Lownes, John Beale, and Augustine Mathewes], 1627. Call number: STC 11395 Copy 1 and LUNA Digital Image.

Science and the Sea

Learn more about the first modern work on ocean science in this audio.

- Isaac Vossius. A treatise concerning the motion of the seas and winds. London: H[enry]. C[ruttenden], 1677. Call number: 155– 695q; displayed title page.

Meaningful Morals

Listen to Steve Mentz discuss Henry Peacham's visual use of the sea.

- Henry Peacham. Minerva Britanna or A garden of heroical devises, furnished, and adorned with emblemes and impresa’s of sundry natures, .... London: Wa: Dight, [1612]. Call number: STC 19511 Copy 1; displayed p. 165.

Hear about William Bourne's book, A Regiment for the Sea.

- William Bourne. A regiment for the sea, containing verie necessarie matters for all sorts of men and travailers. London: T. Est, 1592. Call number: STC 3427; displayed title page.

A Disoriented Sailor

Learn about one crew member of the ship The Sovereign of the Sea, the sailor Edward Barlow, in this audio.

- Ship model of The Sovereign of the Seas. Call number: na.

Legend of Captain Jones

Hear about the amazing adventures of Captain Jones.

- David Lloyd. The legend of Captain Jones: relating his adventure to sea: his first landing, and strange combat with a mighty bear.. London: E. Okes and Francis Haley, 1671. Call number: L2633; displayed frontispiece foldout.

Beware of Scurvy!

Hear about early writings on the cure to the disease of scurvy.

- Everard Maynwaringe. Morbus polyrhizos & polymorphæus. A treatise of the scurvy, examining opinions of the most solid and grave writers, concerning the nature and cure of this disease. London, 1669. Call number: 163- 868q; displayed title page.

Armchair Atlas

Listen to Steve Mentz discuss the oversized Atlas maritimus & commercialis and explore an interactive version of the atlas here.

- FACSIMILE. Atlas maritimus & commercialis; or, a general view of the world, so far as relates to trade and navigation. London: for James and John Knapton, William and John Innys; John Darby; etc., 1728. Call number: HF1023.A8 Cage and LUNA Digital Image.

Shipwrecked

Listen to actor Maury Sterling in a dramatic reading of the shipwreck in Robinson Crusoe.

- Daniel Defoe. The farther adventures of Robinson Crusoe, being the second and last part of his life, and strange surprizing accounts of his travels round three parts of the globe. London: W. Taylor, 1719. Call number: 166– 097q; displayed foldout before title page.

Dances with Goats

Learn about what is happening in this picture of Alexander Selkirk, the real life inspiration behind Defoe's Robinson Crusoe in this audio.

- LOAN courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University. Alexander Selkirk Makes his Cats and Kids dance before Captn. Cook and his Company. From An historical account of all the voyages round the world performed by English navigators. Volume the second. [London: F. Newberry, 1774].

Video

Steve Mentz, curator of the exhibition, shares some of the tools used by sailors in the 17th and early 18th centuries.

Let's Talk Live

Visit this link to see exhibition curator Steve Mentz talks with News Channel 8's Melanie Hastings on "Let's Talk Live!" about Lost at Sea.

Suggestions for further reading and research

To learn more about the ocean, this exhibition includes Four Salty Top-Ten Lists of stories, poems, histories, and locations.

Ocean Stories

These titles are listed chronologically.

- Homer, The Odyssey (~ 8th century BCE)

- Luís vaz de Camões, The Lusiads (1572)

- William Shakespeare, The Tempest (1611)

- Daniel Defoe, Robinson Crusoe (1719)

- Tobias Smollet, Roderick Random (1748)

- Herman Melville, Moby-Dick (1851)

- Victor Hugo, The Toilers of the Sea (1866)

- Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim (1900)

- Patrick O’Brian, The Aubrey-Maturin Novels (1969–2004)

- Yann Martel, Life of Pi (2002)

Ocean Poems

These titles are listed chronologically.

- George Gideon, Lord Byron, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (Canto 4) (1818)

- Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself” (Part 22) (1855)

- Emily Dickinson, “Exultation is the going…” (1859)

- Ezra Pound, The Cantos (Canto 1) (1922)

- Robert Frost, “Neither out far nor in deep” (1936)

- Wallace Stevens, “The Idea of Order at Key West” (1936)

- Édouard Glissant, “Ocean” (1954)

- Derek Walcott, “The Sea is History” (1979)

- Mary Oliver, “The Sea” (1990)

- Anthony Caleshu, “Of the Less Erroneous Pictures of Whales” (2007)

Ocean Histories

- E.D.H. Taylor, The Haven-Finding Art (1957)

- Rachel Carson, The Sea Around Us (1962)

- Fernand Braudel, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II (1972)

- J. H. Parry, The Discovery of the Sea (1974)

- Alain Corbin, The Lure of the Sea: The Discovery of the Seaside, 1750 – 1840 (1994)

- Deborah Cramer, Great Waters: An Atlantic Passage (2001)

- Philip Steinberg, The Social Construction of the Ocean (2001)

- Josiah Blackmore, ed., The Tragic History of the Sea (2001)

- Bernhard Klein and Gesa Mackenthun, eds., Sea Changes: Historicizing the Ocean (2003)

- Callum Roberts, The Unnatural History of the Sea (2007)

Ocean Centers

- The National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

- Mystic Seaport, Mystic, CT

- The New Bedford Whaling Museum, New Bedford, MA

- The South Street Seaport Museum, New York City

- The John Carter Brown Library at Brown University, Providence, RI

- The Mariners' Museum, Newport News, VA

- “On the Water”, Smithsonean Museum of American History, Washington, DC

- Maritime Museum, Barcelona, Spain

- Sheepvaart Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- Nantucket Whaling Museum, Nantucket, MA