Manifold Greatness exhibition material

This article offers a comprehensive list of items included in Manifold Greatness: The Creation and Afterlife of the King James Bible, one of the Exhibitions at the Folger.

For additional resources on the topic, also see the Folger's finding aid of primary source materials related to the King James Bible.

Martyrs and Heretics: Translating the Bible into English (case 1)

Late medieval England was the only place in Europe where you couldn’t read the Bible in your own language. At the time, Bibles printed in the vernacular, or local, language were prohibited by the Roman Catholic Church. Church authorities believed that there needed to be an intermediary between the reader and the scripture.

William Tyndale, one of the major figures of the English Protestant Reformation, left England for the Continent to safely translate the New Testament into English. As Tyndale labored abroad, the English religious authorities attacked him as a heretic for his unauthorized translations and confiscated and burned copies of the text. In 1536, Tyndale was put to death near Brussels for heresy. The next year, his once-banned translations reappeared as part of Matthew’s Bible, a 1537 English edition of the Bible which published Tyndale's New Testament in tandem with John Rogers' translation of the Old Testament. Though the level of his contribution is disputed, a great portion of the King James Bible consists of Tyndale's text.

Items included

- LOAN courtesy of The Ohio State University. Fragment from William Tyndale. Pentateuch, the first five books of the Old Testament. Antwerp, 1530. OSU Call number: BS1222 1530; displayed Exodus 27.

- William Tyndale. The obedyence of a Chrysten man. London, 1537? Call number: STC 24447.2; displayed fol. xi.

- LOAN courtesy of the Christoph Keller, Jr. Memorial Library of the General Theological Seminary. Biblia the Byble: that is, the holy Scrypture of the Olde and New Testament, faythfully translated in to Englyshe. Cologne?: E. Cervicornus and J. Soter, 1535. GTS Call number: BS145 1535; displayed closed with facsimile of title page.

- LOAN courtesy of Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. The Junius Manuscript, ca. 1000 CE or before. Bodleian Call number: MS Junius 11; displayed image of Adam and Eve.

- LOAN courtesy of Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. Wycliffite Old Testament manuscript. ca. 1380s–90s. Bodleian Call number: MS Bodl. 959; displayed f. 332r.

Champions of the English Bible (wall after case 1)

- Wall Panel with images from John Foxe. Actes and monuments. London: John Daye, 1570. Call number: STC 11226 and LUNA Digital Image.

Printing the Bible in English (case 2)

When Henry VIII broke with the Roman Catholic Church in 1533 to marry Anne Boleyn, effectively establishing the modern Church of England, English Bible translations had a major change of fortune. The Coverdale Bible, an expatriate English Bible produced by Miles Coverdale in 1535, praised Henry in its dedication and included his picture on its title page.

An anonymously published Bible credited to “Thomas Matthew,” Matthew’s Bible, included both Tyndale’s work and part of the Coverdale Bible and was licensed and distributed to some English parishes.

Under Henry, the 1539 Great Bible, a revised edition of Matthew’s Bible, became the first authorized English Bible. This woodcut, one of many in the Great Bible, is from Exodus. Moses, who was conventionally drawn with horns, is seated like an English shepherd with his flock as God speaks from a burning bush.

Items included

- FACSIMILE from The National Archives, London. Letter from Cranmer to Cromwell commending Matthew’s Bible and requesting license to publish. August 4, 1537. Reference: SP 1/123.

- FACSIMILE from New York Public Library. Henry VIII. Proclamacion, ordeyned by the Kynges majestie, with the advice of his honorable counsayle for the Byble of the largest and greatest volume, to be had in every churche. London: Richard Grafton & Edward Whitchurch, 1541. (NYPL Call number: STC 7793).

- The Byble, which is all the holy Scripture: in whych are contayned the Olde and Newe Testament truly and purely translated into Englysh by Thomas Matthew. Antwerp: Matthew Crom for Richard Grafton and Edward Whitchurch, London, 1537. Call number: STC 2066; displayed fol. Lcxlvi. LUNA Digital Image.

- The Byble in Englyshe, that is to saye the content of al the holy scrypture, both of ye olde, and newe testament, with a prologe therinto, made by the reuerende father in God, Thomas archbysshop of Cantorbury. London: Edward Whitchurch, 1540. Call number: STC 2070; displayed title page.

Comparing Bibles (vitrine before case 3)

Commentary in two sixteenth-century Bible translations reflects strong theological differences between Christian denominations. The Geneva Bible was famous for its copious marginal notes, which guide the reader with alternative translations, cross-references to other relevant passages, and interpretations, similar to today's English Standard Version of the study Bible. Most of its notes were uncontroversial, but a few reflect the radical Calvinism of the translators. The harshly anti-Catholic commentary in the Geneva Bible prompted responses from Catholics in their own translations of the Bible. For example, marginal notes on the identity of the Whore of Babylon in the Geneva Bible and the Rheims Bible are in sharp argument with each other.

Items included

- The Bible. Translated according to the Ebrew and Greeke, and conferred with the best translations in divers languages. London: Christopher Barker, 1586. Call number: STC 2145; displayed fol. 552v.

- The New Testament of Jesus Christ, translated faithfully into English, out of the authentical Latin, according to the best corrected copies of the same, diligently conferred with the Greeke and other editions in divers languages. Rheims: John Fogny, 1582. Call number: STC 2884 copy 1; displayed p. 724.

Bible and Crown: The Road to Hampton Court (case 3)

Elizabeth I’s bishops realized that the relatively new, accessibly designed Geneva Bible posed an unwelcome contrast to the old, 1539 Great Bible of Henry VIII. The Geneva Bible was too hotly Protestant for the comfort of the English establishment. In response, the Church of England produced the Bishops’ Bible, a largely unsuccessful competitor to the Geneva Bible. It shared a key element with the Great Bible: a prominent picture of the ruler of England—in this case, the young Elizabeth—on its title page.

Items included

- The holie Bible. The "Bishops' Bible." [London: Rycharde Jugge], 1568. Call number: STC 2099 copy 3; displayed cover.

- FACSIMILE from The National Archives, London. Matthew Parker. Manuscript list of the bishops working on the Bishops’ Bibleca. 1568. Reference: SP 12/48.

- FACSIMILE from The National Archives, London. Letter from Matthew Parker, Archbishop of Canterbury to William Cecil, Lord Burghley. Lambeth, September 12, 1568. Reference: SP 12/47 folio 159.

- FACSIMILE from National Portrait Gallery, London. John Payne. Hugh Broughton. Line engraving, 1620. Reference: NPG D11084 and image.

- Hugh Broughton. An epistle to the learned nobilitie of England. Middleburgh: Richard Schilders, 1597. Call number: STC 3862a; displayed title page.

Queen and Court in the Bishops’ Bible (wall above case 3)

- Wall Panel with images from The holie Bible. The "Bishops' Bible." [London: Rycharde Jugge], 1568. Call number: STC 2099 copy 3 and LUNA Digital Image and Binding image on LUNA.

King James and the Hampton Court Conference (case 4)

Growing up, James I navigated the factions of Scottish politics, divisions heightened by religious disputes over such matters as the appropriate role, or lack thereof, for bishops in the Scottish church. Even as a new English king, he drew on his experience with the Scottish church at his 1604 Hampton Court conference with Puritans and Anglican bishops, twice remarking, “No bishop, no king.”

It was this conference that ultimately yielded James’s approval for the massive project that resulted in the 1611 King James Bible. Midway through the three-day conference, the scholar and clergyman John Rainolds asked the king to approve the production of a major new English translation of the entire Bible. James agreed. Its dedication, which is not always reprinted today, highlights the translators’ typically fervent dedication to their king—the “Sun in his strength” who cleared away “clouds of darkness” after Elizabeth’s death.

Items included

- William Barlow. The svmme and svbstance of the conference, which, it pleased his excellent Maiestie to haue with the lords, bishops, and other of his clergie, (at which the most of the lordes of the councell were present) in his Maiesties priuy-chamber, at Hampton Court. January 14. 1603. London: John Windet for Mathew Law, 1604. Call number: STC 1456; displayed p. 45 and LUNA Digital Image.

- Edward H. Fitchew. Wolsey’s Palace. Ink wash and pencil, ca. 1880–99. Call number: ART Box F546.5 no.1 (size S) and LUNA Digital Image.

- James I, King of England (1566–1625). The workes of the most high and mightie prince, James by the grace of God, King of Great Britaine, France and Ireland, defender of the faith, &c. London: Robert Barker and John Bill, 1616. Call number: STC 14344 copy 2; displayed title page.

- University of Oxford. The answere of the vicechancelour, the doctors, both the proctors, and other, the heads of houses in the Universitie of Oxford. Oxford: Joseph Barnes, 1603. Call number: STC 19012 (Bd.w. STC 1458 copy 2); displayed p. 1 of first book.

John Rainolds’ Biblia Sacra (vitrine after case 4)

- LOAN courtesy of Corpus Christi College, University of Oxford. Biblia sacra, Hebraice, Graece, et Latine. Heidelberg, 1599. Corpus Christi Call number: CZ.11.4 vol. 2; displayed p. 606.

Translating the King James Bible (case 5)

Translating the King James Bible relied upon collaboration. The translators worked and met in committees for years at Oxford, Cambridge, and Westminster Abbey. Earlier editions of English Bibles guided the translators, who drew freely from many English Bibles. The literary masterpiece that they created includes countless lines and phrases from the diverse editions of the past.

The four dozen translators who produced the King James Bible included some of the best scholars in England. Every regius professor—every professor who held a royally endowed position—in Greek, Hebrew, or divinity at Oxford or Cambridge served on the project. All but one of the translators were also clergymen—among them, vicars, deans, bishops, archbishops, and royal chaplains.

Five of the translators died between 1604, when the project was approved, and 1611, when the translation was printed, and some of them were replaced. No single, definitive list of the many people who worked on the translation exists. Inconsistent records and questions about which scholars replaced those who died have added more uncertainty over time. Many researchers use an approximate figure of 47 translators.

Items included

- FACSIMILE from British Library Board. The list of translators. British Library Call number: MS Harley 750 fol. 1r.

- FACSIMILE from British Library Board. The Rules for the Translators. British Library Call number: MS Harley 750 fol. 1v.

- LOAN courtesy of Corpus Christi College, University of Oxford. John Bois’ manuscript notes of the proceedings. Corpus Christi Call number: MS 312; Displayed f.61.

- LOAN courtesy of His Grace the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Trustees of Lambeth Palace Library. Manuscript Draft of the Pauline and Catholic Epistles. Early 17th century. Order no: MS 98.

Portrait of John Rainolds (wall above case 5)

As a key Puritan delegate at the Hampton Court conference, John Rainolds obtained the king's approval for the King James Bible project, and he cared deeply about the translation. Rainolds, however, did not live to see it completed. Working with his company, which met in his Oxford rooms, he was able to translate most of his assigned portion of the Old Testament before dying of consumption in 1607.

- FACSIMILE from Corpus Christi College, University of Oxford. Portrait of John Rainolds (1549–1607). Oil on panel, 17th century. Image.

Translators' Marks (vitrine after case 5)

The King James Bible translators began with the Bishops’ Bible as their base. Each was given an unbound copy of the 1602 edition. Only one survives, complete with marked additions and deletions.

- LOAN courtesy of The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. The holie Bible conteynyng the olde Testament and the newe. London, 1602. Bodleian Call number: Arch. A b.18; displayed fol. 417v-418r.

Printing the King James Bible (case 6)

Printing the King James Bible was an expensive assignment for the king’s printer, Robert Barker. Though he received the royal patent for printing the edition, its publication was not sponsored by royal funds, and Barker had to raise the money himself. Paper, usually imported from the continent, was the most expensive part of printing during this period.

The three main people that worked at a print shop were the compositor, the person who set the type, and two pressmen, one who would apply the ink, and another who would put the paper onto the tympan and physically print the pages once type and ink were set.

It is unclear how many copies of the King James Bible's first edition were printed, but scholars estimate between five hundred and a thousand. It is also not clear long it took Barker to complete that print run; scholars believe the process took about a year, as he began raising money in October of 1610, and the book has an imprint date of 1611.

Items included

- John Selden. Table-talk. London: For E. Smith, 1689. Call number: S2437; displayed p. 3.

- FACSIMILE. The Holy Bible, conteyning the Old Testament, and the New: newly translated out of the originall tongues. London: Robert Barker, 1611. Call number: STC 2216; displayed Ruth 3:15 and LUNA Digital Image.

- FACSIMILE. The Holy Bible, conteyning the Old Testament, and the New: newly translated out of the originall tongues. London: Robert Barker, 1613. Call number: STC 2224 copy 1; displayed Ruth 3:15 and LUNA Digital Image

- Hugh Broughton. A censure of the late translation for our churches. Middleburgh: Richard Schilders, 1611. Call number: STC 3847; displayed title page and LUNA Digital Copy.

- LOAN courtesy of Washington National Cathedral. The Holy Bible, conteyning the Old Testament, and the New: newly translated out of the originall tongues. London: Robert Barker, 1611. Cathedral Call number: STC 2216; displayed front board and title page. Image.

- The Holy Bible, conteyning the Old Testament, and the New: newly translated out of the originall tongues. London: Robert Barker, 1611. Call number: STC 2216; displayed Adam and Eve from family tree.

Anatomy of the King James Title Page (wall between case 6 and 7)

The 1611 Bible is known today as the King James Bible, the King James Version, or the Authorized Version, but none of those names are included in the formal title. The text here does note, though, that the Bible was translated "by His Majesty's special commandment" and printed by the King's Printer, Robert Barker.

Items included

- Wall Panel with enlarged facsimile of The Holy Bible, conteyning the Old Testament, and the New: newly translated out of the originall tongues. London: Robert Barker, 1611. Call number: STC 2216; displayed title page. Annotated image explaining iconography of title page.

Misprints and Misfortunes (case 7)

Generally, the compositor preparing a page for print worked off a manuscript of the text, reading the manuscript while pulling type from the case. Since a compositor knew the layout of the case by heart, it was a very mechanical exercise. If the type was not set back into the case properly after use, errors occurred. During the printing process, a proof would be given to a corrector, who would mark any changes that needed to be made to the page. Pressmen kept printing during this review, however, contributing to the minute changes in various copies of Early Modern books.

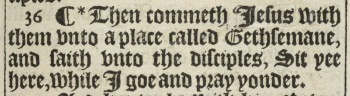

In a folio edition from 1613, "Jesus" at one point is mistakenly printed as "Judas." This copy become known as the Judas Bible. In the Folger copy, someone corrected this mistake by pasting the name "Jesus" over "Judas; "a bit of the J from "Judas" still sneaks around the side of the paste-down correction.

The most infamous typo found in the King James Bible is from an edition now called the Wicked Bible. This Bible, from 1631 owes its name to the famous misprint of the seventh commandment in Exodus 20:14 as ‘Thou shalt commit adultery’. The offending Bibles were seized and the printer, Robert Barker, was prosecuted and fined; copies of it are extremely rare. Recent research points to industrial sabotage: in three surviving copies another error, the printing of ‘great ass’ for ‘greatness’ in Deuteronomy 5:24, has apparently been deliberately obscured with ink.

Items included

- LOAN courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries University of Oxford. The Holy Bible, conteyning the Old Testament, and the New: newly translated out of the originall tongues. London: Robert Barker, 1631. Bodleian Call number: Bib. Eng. 1631 f.1; displayed Exodus 20.

- FACSIMILE from The National Archives, London. Acts of the High Commission. Record of fines imposed on Robert Barker and Martin Lucas, the King’s Printers trial. October 10, 1633.

- The Holy Bible, conteyning the Old Testament, and the New: newly translated out of the originall tongues. London: Robert Barker, 1613. Call number: STC 2224 copy 1; displayed Matthew 26:36 with enlarged facsimile of typographical error “Judas” set instead of “Jesus.”

- Composing stick with Wicked Bible typographical error “Thou shalt commit adultery” set. (Prop)

Listening to the King James Bible (scene after case 7)

- Computer with interactive “Read the Book” feature also available on Manifold Greatness website.

- LOAN courtesy of The Lutheran Church of the Reformation. Lectern and pew.

A Variety of Forms for a Variety of Readers (case 8)

- Arthur Woolley. Part of the Holy Bible. Manuscript, late 1600s. Call number: V.a.529; displayed fol. 2 with facsimile of title page.

- LOAN courtesy of [Library of Congress. A Curious Hieroglyphic Bible, of, Select passages in the Old and New Testaments. Worcester, MA: Isaiah Thomas, 1788. LC Call number: BS560 1788 Am Imp Copy 1; displayed p. 6–7 and LC Digital Copy.

- The Holy Bible: containing the Olde Testament and the New. London: Robert Barker, 1633. Call number: STC 2308; displayed closed and LUNA Digital Image.

- The third part of the Bible, (after some diuision) containing fiue excellent bookes, most commodious for all Christians. London: Bonham Norton & John Bill, 1626. Call number: STC 2278 copy 1; displayed flyleaf inscription by Justinian Isham, and LUNA Digital Image.

- The New Testament of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. London: Robert Barker, 1630. Call number: STC 2937; displayed dos-a-dos binding.

- The Holy Bible, containing the Old Testament and the New. London: Charles Bill and the Executrix of Thomas Newcomb, 1701. Call number: 207- 237b; displayed closed, and LUNA Digital Image and Binding image on LUNA.

The Family Bible (case 9)

As advances in nineteenth-century printing made Bibles more widely available, the family Bible became a domestic institution, a substantial book that might be displayed in the parlor. Families recorded births, marriages, deaths, prayers, and even recipes in such Bibles, which were often handed down to later generations. More than a century later, many of these older family Bibles still remain in private homes.

Items included

- The Holy Bible, containing the Old Testament and the New. London: John Bill and Christopher Barker, 1676. Call number: 265076.1; displayed Rebekah Fisher inscription with enlarged facsimile of engraved clasp, and LUNA Digital Image.

- LOAN courtesy of Hannibal Hamlin. The Holy Bible Containing the Old and New Testaments Translated out of the Original Toungues. Boston: B.B. Mussey, 1841. Displayed Hamlin family records before New Testament.

- The Holy Bible, containing the Old Testament and the New. London: Robert Barker and John Bill, 1630. Call number: STC 2290; displayed Hart family records before dedication.

- The Holy Bible, conteyning the Old Testament and the New. London: Robert Barker, 1639. Call number: STC 2335; displayed Dewitt family records before New Testament, and LUNA Digital Image.

George Washington’s Family Bible (vitrine before case 10)

- LOAN courtesy of George Washington National Masonic Memorial. The Self-Interpreting Bible: Containing the Sacred Text of the Old and New Testaments. New York: Hodge and Campbell, [1792]. Displayed Washington family records before New Testament.

Shakespeare and the King James Bible: Debunking the Myth (case 10)

The myth that Shakespeare was involved in translating the King James Bible lingers. Two widespread nineteenth-century cultural beliefs combined to generate Shakespeare's "involvement" with the project: that the King James Bible is the greatest achievement of English prose writing, and that Shakespeare is the greatest English writer. The translators of the King James Bible were primarily concerned with making their translation as accurate as possible. Whatever style the translation has is an accidental by-product. Furthermore, all but one of the translators were clergymen, and all of them were exceptionally knowledgeable about ancient languages, making Shakespeare's participation in the translation even less likely.

- The Holy Bible, contayning the Old Testament and the New. London: Bonham Norton and John Bill, 1629. Call number: STC 2286; displayed Psalm 46 with enlarged facsimile of Psalm 46.

- FACSIMILE from Widener Library, Harvard University. The Flaming Sword. Chicago: Guiding Star Publishing House. Vol. 13, November 18, 1898. Harvard Call number: (Soc 705.2 ); displayed cover and Google Books Digital Copy.

- Goldie Jr. Our Shakespeare wrote the Bible. London: Walter Jenn, 1929. Call number: Sh.misc. 770; displayed closed, and LUNA Digital Image.

- The Bible-Shakespeare Calendar. Compiled by Edgar C. Abbott. Boston, MA, 1916. Call number: Sh.Misc. 2102; displayed closed and LUNA Digital Image.

- Rudyard Kipling. “Proofs of Holy Writ.” London: George Newnes, 1934. In The Strand magazine vol. 87, no. 520 (Apr. 1934). Call number: 265- 425q; displayed p. 354-55.

Sailing to America (case 11)

One edition of the King James Bible, owned by John Alden, came over on the Mayflower with Alden in the same year it was printed, 1620. Alden, a member of the ship's crew, stayed on as a colonist. Most of the Pilgrims preferred the older Geneva Bible. Over the next few decades, however, the King James Bible became the preeminent Bible in the colonies, as it did in England.

The Aitken Bible is the first complete English Bible printed in America and bearing an American imprint; it was approved and recommended by Resolution of the U.S. in Congress assembled, Sept. 12, 1782, authorizing the publisher "to publish this recommendation in the manner he shall think proper".

Items included

- LOAN courtesy of Pilgrim Hall Museum. The Holy Bible, containing the Old Testament and the New London: Bonham Norton and John Bill, 1620. Displayed closed.

- LOAN courtesy of Library of Congress. The Holy Bible … Translated into the Indian Language. Cambridge, MA: Samuel Green and Marmaduke Johnson, 1663. LC Call number: BS345.A2 E4 1663 Bible Coll; displayed title page.

- LOAN courtesy of Library of Congress. The Holy Bible containing the Old and New Testaments. Philadelphia: Robert Aitken, 1782. LC Call number: BS185.1782 .P5 Vol. 1, copy 1; displayed Congressional authorization page.

- LOAN courtesy of National Park Service, Frederick Douglass National Historic Site. The Holy Bible containing the Old and New Testaments. London: Oxford University Press. Displayed closed with enlarged facsimile of Frederick Douglass’ name embossed on cover.

- LOAN courtesy of The American Bible Society. New Testament. King James Version. New York: American Bible Society, 1863. Displayed union soldier Thomas P. Meyer inscription.

Cross-Atlantic Echoes: English and American Literary Influences (case 12)

Like any major cultural work, the King James Bible of 1611 has influenced countless aspects of art, society, and culture—in addition, of course, to its spiritual role. Perhaps the most enduring and diverse of these cultural influences has been its influence on literature, which encompasses poems, novels, and other writings spanning four centuries and every English-speaking literary tradition.

Authors ranging from radical nonconformists and skeptics to others steeped in their established faith have found inspiration in the language of the King James Bible. And their works, in turn, have often inspired other creations, from music, works of visual art, and movies to new books and poems—each one a possible focal point for still more widening ripples of the enduring influence of the King James Bible.

For example, from its publication in 1678 until the twentieth century, The Pilgrim’s Progress was one of the most widely read books in English. It is a pastiche of biblical characters, places, and passages, most of them in the language of the King James Bible. Many of Christian’s adventures are biblical, too, as when he walks through “the valley of the shadow of death” that is described in Psalm 23.

Items included

- John Bunyan. The pilgrim’s progress from this world, to that which is to come. London: for Nath. Ponder, 1680. Call number: 207- 214q; displayed title page.

- John Milton. Paradise lost. London: for Jacob Tonson, 1692. Call number: M2150; displayed plate facing B1r.

- LOAN courtesy of Library of Congress. William Blake (1757–1827). The marriage of Heaven and Hell. London, ca. 1794. LC Call number: PR4144 .M3 1794 Rosenwald Coll.; displayed Plate 10.

- LOAN courtesy of Library of Congress. Herman Melville (1819–91). Moby Dick, or The whale, by Herman Melville. Illustrated by Rockwell Kent. Chicago: The Lakeside Press, 1930. LC Call number: PS2384 .M6 1930 Vol. 1, copy 1; displayed p. 58-59.

- LOAN courtesy of Library of Congress. Allen Ginsberg (1926–97). Howl, and Other Poems. San Francisco: City Lights Pocket Bookshop, 1956. LC Call number: PS3513.I74 H6; displayed closed.

Cultural Influences (case 13)

The King James Bible has appeared in a vast variety of cultural settings in the centuries since 1611. Authors and poets allude to its passages; composers from Handel to Bob Marley have set its words to music. Animators and visual artists are inspired by its phrases. Presidents often use King James Bibles at their inaugurations, and many families still keep records of key events in copies that become family heirlooms.

The farthest physical reach of the King James Bible to date occurred on Christmas Eve, 1968, when the three Apollo 8 astronauts orbiting the Moon read from Genesis, using the King James Bible text. A global audience estimated at half a billion heard and watched their live television broadcast, making it the most-watched broadcast in history at that time.

Handel's Messiah

Composed in London in three weeks in the late summer of 1741, George Frideric Handel’s Messiah is the most enduringly popular and widely known musical work shaped by the King James Bible. Most of its text consists of passages from the King James Bible. Only lines from the psalms are from a different source, the Book of Common Prayer, which incorporates Miles Coverdale’s translations from the 1539 Great Bible.

Handel’s librettist, Charles Jennens, often used lines from the King James Bible word-for-word, although he sometimes made small changes to fit the assembled passages together. The idea of a “Scripture Collection,” as Jennens modestly called it, was not unique to Messiah, but the concept reached new heights in the oratorio’s complex narrative, which weaves together Old and New Testament texts.

Eighteenth-century audience members bought word-books like the one shown here to read Jennens's libretto; one clergyman preached 50 sermons on it. Today, Messiah performances are a ubiquitous tradition in the United States and other countries, offering annual exposure to the language of the King James Bible with the energy of live performance.

A live audio recording of selections from Handel's Messiah by the Folger Consort and the Choir of Magdalen College, Oxford is available for free download at CD Baby.

Modern Life

Examples of its more contemporary influence range from the post-apocalyptic film, The Book of Eli (2010), in which characters fight over a surviving copy, to the almost entirely scriptural words of the song Turn! Turn! Turn!, recorded by the Byrds in 1965, to the lyrics of the late reggae superstar Bob Marley. Elvis's love of gospel music, itself often inspired by the language of the King James Bible, is well-known. Interestingly, his Grammy Awards come from his gospel records rather than his rock and roll music. Millions of copies of the King James Bible are placed in hotel rooms by Gideons International, and political and civic leaders continue, on occasion, to quote from its language.

Items included

- George Frideric Handel. Messiah: an oratorio in score as it was originally perform’d. London: Preston, ca. 1807. Call number: M2000.H13 M8 Cage.

- Photograph of Earthrise and Lunar horizon from Apollo 8. December, 1968. Public domain.

- Photograph of Martin Luther King, Jr. giving “I Have a Dream” speech. Washington, DC. August 28, 1963. Public domain.

- LOAN courtesy of Elvis Presley Enterprises, Inc., “Graceland.” The Holy Bible Containing the Old and New Testaments Translated out of the Original Toungues. Rembrandt Edition. New York: Abradale Press, 1959?. Displayed closed.

- FACSIMILE from Lee Mendelson Film Productions, Bill Melendez Productions, United Feature Syndicate (UFS) and the Charles M. Schulz Museum and Research Center, Santa Rosa, California. Charles M. Schulz (1922–2000). A Charlie Brown Christmas. Burlingame CA: 1965

- DVD of The Book of Eli. Directed by Albert and Allen Hughes. Written by Gary Whitta. Warner Bros., 2010. (Prop)

- R. Crumb. The Book of Genesis Illustrated. Illustrated by R. Crumb. New York: Norton & Co., 2009. (Prop)

The Democracy of Bibles (case 14)

The King James Bible translators might be pleased be to learn that their work has endured in profound ways over the course of four centuries. English Bibles are now accessible in a way they and other earlier translators such as William Tyndale never imagined. The Bibles presented in this case demonstrate how universal English translations of the Bible have become. Today there is truly a democracy of Bibles, an edition for every type of person.